The “Great Reset”: Prospects and Risks

The “Great Reset,” a blueprint of wide-ranging changes meant to lead to a greener and fairer society, is gaining momentum. It proposes an ambitious redesign of today’s economic system. How suitable a model is it for our post-Covid future?

In a nutshell

- The "Great Reset" model advocates broad systemic changes

- Significant state intervention would be required to make it work

- Its implementation could lead to a deficit in democracy

“Great Reset” seems to be the latest catchphrase. The concept was coined by German economist Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum (WEF), held in Davos each year. In the July 2020 book “COVID-19: The Great Reset,” he and his French coauthor Thierry Malleret describe Covid-19 as an “opportunity” to “reset” the world. This new reality would be “greener, smarter, fairer,” avoiding the “systemically interdependent” risks of climate change, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse. Already, the pandemic has led to “polarization, nationalism, racism, and increased social unrest and conflict.” The authors posit that these challenges must be addressed from a systemic perspective.

The International Monetary Fund and companies like Microsoft have joined in on the trend. The United Kingdom’s Prince Charles thinks we need a “new Marshall aid plan for nature, people and planet” and “a shift in our economic system” toward “sustainable inclusive growth.” According to the book, Covid recovery funds should be channeled into green stimulus measures – which they frequently are, as in the European Union for example. The authors also discuss growth and stagnation, fiscal and monetary policies, as well as geopolitical challenges, treading a fine line between prediction and prescription. The associated podcast series is more openly prescriptive.

Resetting ourselves

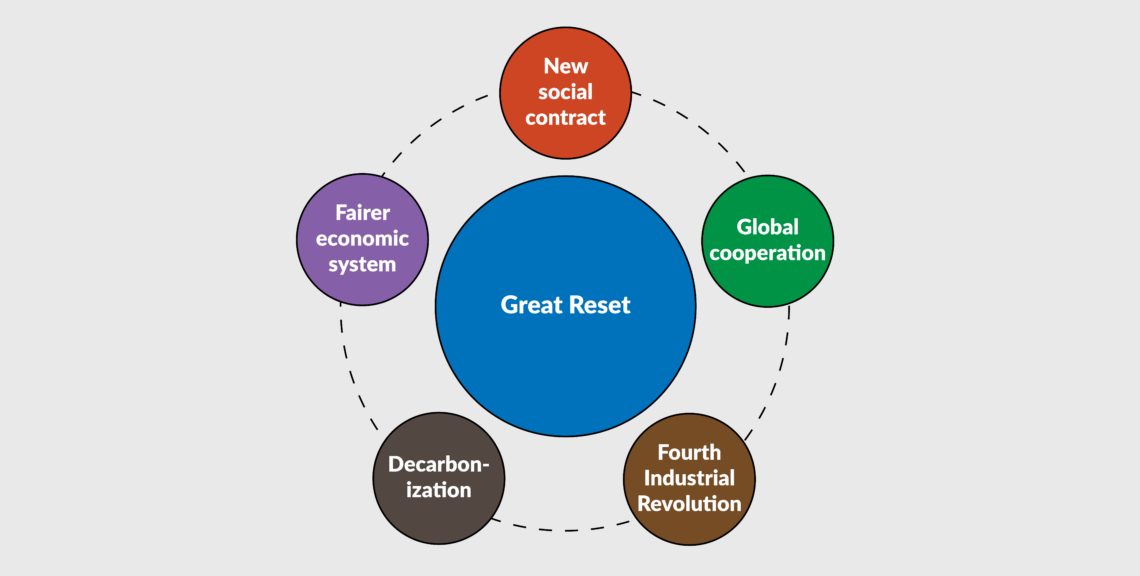

The Great Reset concept covers five priorities. First, it envisions a new social contract that fosters social inclusion, decreases the burden passed on to future generations, and reduces inequality within and between countries, defusing social unrest. Great Reset thinkers believe the health crisis revealed shocking inequality. In the United States, for example, the poor, unable to work remotely, died in greater numbers. These frontline heroes of the pandemic are most often paid a fraction of what white-collar executives earn. The authors also see the younger generation’s activism and movements like the Yellow Vests as a demand for more radical policies. They believe in a “return of the State” after what they see as a period of retreat since the Thatcher and Reagan era.

“Great Reset” thinkers believe the health crisis revealed shocking inequality.

Their second priority is a decarbonization of the economy to fight global warming. The movement’s advocates fear the health crisis could eclipse climate concerns, especially given today’s low hydrocarbon prices. They would promote green growth with carbon taxes and public and private partnerships, which they say could create millions of jobs. Citing Italian economist Mariana Mazzucato, the authors suggest we should “actively create and design markets ensuring sustainable and inclusive growth” where partnerships with businesses involving public funds should be motivated by public interest and not profit. Messrs. Schwab and Malleret also support “a massive repurposing of subsidies” and “a fundamental redesign of incentive systems.”

The third priority is an intensification of the Fourth Industrial Revolution based on digitalization, not only to increase productivity but also to better manage nature – for example, avoiding pandemics like the most recent one.

Facts & figures

The fourth pillar of the Great Reset is a shift from “short-term” shareholder capitalism to a more equitable and greener “longer-term” stakeholder capitalism. For example, while businesses and consumers generate “negative externalities,” that is, pollution and waste, this social cost is not compensated by private emitters. The new ESG paradigm (environmental, social governance) would solve these issues, with less focus on short-term profits and more emphasis on the common good.

Finally, closer global cooperation, especially on environmental issues, would lead the world out of national selfishness. Given the rise of nationalist and anti-globalization sentiments during Covid, the negative impact on growth could be substantial. The authors suggest a more inclusive, equitable and sustainable form of globalization, which requires strong leadership to establish global governance. They believe Covid-19 revealed a lack of international coordination, even within supranational blocs like the EU. The Great Reset does not advocate a global government, but promotes more international cooperation, with “global shapers” and a “global civil society” influencing national public policy.

Facts & figures

The Great Reset – Five Priorities

- No. 1: a new social contract that fosters social inclusion,

- No. 2: a decarbonization of the economy to fight global warming,

- No. 3: an intensification of the Fourth Industrial Revolution based on digitalization,

- No. 4: a shift from "short-term" shareholder capitalism to "longer-term" stakeholder capitalism,

- No. 5: a closer global cooperation on key issues.

“Great Reset” Policymaking

One WEF policy paper lays out more concrete steps to “protect and restore natural capital assets” (ecosystems, green urban infrastructure, ecotourism), to “scale regenerative value chains” (agriculture, fisheries, forestry) and “enhance resource productivity” (with “circular models” in building and manufacturing, and “resource-efficient” food systems). Technologies like satellite mapping and monitoring are an essential part of this plan. The tools discussed combine positive and negative incentives, like taxes on emissions, conditional subsidies, and payments for environmental services. Judging by the case studies it praises, the Great Reset relies heavily on entrepreneurial innovation rather than on pure central planning. However, the “reshaping” it envisions would require a top-down approach, especially as it emphasizes the need for “rapid decisions” and “bold policy and decisive political leadership” – to be understood as quick, centralized resolutions.

The “Great Reset” is not a conspiracy. But this does not mean there are no interested parties that would benefit from its policies.

Despite what some believe, the Great Reset is not a conspiracy. The project is relatively transparent. However, this does not mean there are no interested parties that would benefit from its policies. And good intentions do not always lead to beneficial outcomes. In practice, such a “reshaping” of society, no matter how desirable, needs to provide the right incentives to those doing the shaping and their partners. In local or international bureaucracies – that are not democratically elected – just like in private companies, there is often a tendency to create one’s job for profit or power while pretending to work selflessly.

The Great Reset has already started. For example, significant portions of the EU’s Covid-19 recovery funding must go to green projects. The outcome of the strategy will therefore depend on how policymakers handle the classic problems of distorted incentives and limited knowledge in planning. The process will not only affect the environmental efficiency of societies, but also growth, public finances and democracy. The three aspects are interdependent: economically unsound or undemocratic green initiatives that are doomed to fail.

Scenarios

Public finances

The authors call for a “return of the state.” It can be argued that while liberalization and privatization have increased since the 1980s, government intervention (regulation, tax pressure, public spending, and public debt) is significantly high in many countries. The counterproductive effects of high levels of welfare redistribution, like poverty traps, have been documented for some time now. Moreover, this high level of public intervention has been financed by unsustainable debt. More of the same would lead to a pessimistic scenario for public finances, which would also clash with the Great Reset goal of reducing the financial burden left to future generations.

When it comes to inequality, there are two options to regulate remuneration. The first one is price-fixing, which has disastrous effects on market adjustments, creating unemployment. The second one is highly progressive taxation, which also has negative consequences on work incentives and thus on growth and public finances. An alternative could be to stop artificially subsidizing sectors, like finance.

The authors are aware of the dangers of ultra-accommodative monetary policies – which can create bubbles and the accompanying artificial inequality. They also warn against dependence on the “magical money tree.” Unfortunately, the Great Reset would have to rely on precisely these two policies. The only way the concept could lead to a positive outcome is by effectively maximizing green growth with very high returns.

Growth

The Great Reset theory is based on the premise of a significant shift away from fossil fuels. This is a bold assumption. The degree to which alternative energy technologies will catch up will partly depend on the evolution of artificial intelligence. Some observers do not share the optimism of the authors, who believe the green energy sector will be valued at $10.1 billion dollars and will have created 395 million jobs by 2030. This implies the Great Reset theory is probably built on shaky foundations.

Given the public-private partnerships and the subsidies involved, intense lobbying is to be expected. But market economies and central planning are notoriously difficult to reconcile. Supervision committees could be created to enforce the “motivation of public interest.” But there is no guarantee these would be immune to lobbying, potentially creating biases in selecting the best environmental projects. This type of “directly unproductive activity” would reduce competition and overall growth, affecting public finances and, ultimately, our ability to preserve the environment.

Accountability and democracy

Democracy is typically a slow, gradual and consensual process, ideally based on subsidiarity. While the Great Reset advocates maintain this should not be an elite endeavor, it is hard to see how the project could be carried out in a democratic manner. The complexity of the process would make it inaccessible to average citizens. Some fear the model could become a form of crony capitalism, or even communo-capitalism after the Chinese example. (Many success stories mentioned by the Great Reset authors come from China, and in 2018 Dr. Schwab received a “medal of friendship” from President Xi Jinping for having invited the Chinese leader to the World Economic Forum.) In these circumstances, the main scenario here is pessimistic.

Stakeholder capitalism, wherein civil society keeps companies accountable, can be appealing. But it also raises privacy and implementation issues. Who will be entitled to be a stakeholder? On what grounds? And with which powers? The advantage of private shareholders is that the justification and capacities are clear. The boundaries in a stakeholder system are much less clear, possibly leading to uncertainty and legal chaos.

Environment

The environmental outcome of the Great Reset would be constrained by our capacity to afford the measures it envisions, and our ability to ensure these funds genuinely serve the intended causes. With the previous scenarios in mind, it is unclear if the necessary preconditions for success – sound finances, growth and democracy – would be achieved.

The Great Reset covers an enormous scope of topics, and many genuine solutions are offered. However, some of the questions raised here remain unanswered. The movement could prove effective in some aspects. It could rethink the use of several property as a legal bulwark against pollution, beyond only carbon markets. Or it could encourage civil society to reshape consumer behavior by offering broader options than “minimalism” as an alternative to conspicuous consumption.