The end of the Greek bailout program: What comes next?

As the Greek bailout program reaches its scheduled end in August 2018, the country’s government and international community must decide what comes next. Some reforms have been implemented, and the public budget even runs a surplus. But the economy remains vulnerable.

In a nutshell

- Greece is still unable to pay off its debt

- Forcing it to do so would backfire, causing a default and fostering populism

- Cancelling the debt would make the most economic sense, but …

- The EU would be criticized for bailing out Greece merely to avoid Grexit

The Greek bailout saga that began in 2010 is due to come to an end in August. In theory, this means that international organizations – primarily the European Union – will disburse no further resources to sustain the Greek economy and its public finances. Instead, Greece will have to start thinking about how to reimburse its foreign debt, some 320 billion euros of which consist of the funds handed out by international creditors since the relief program took off.

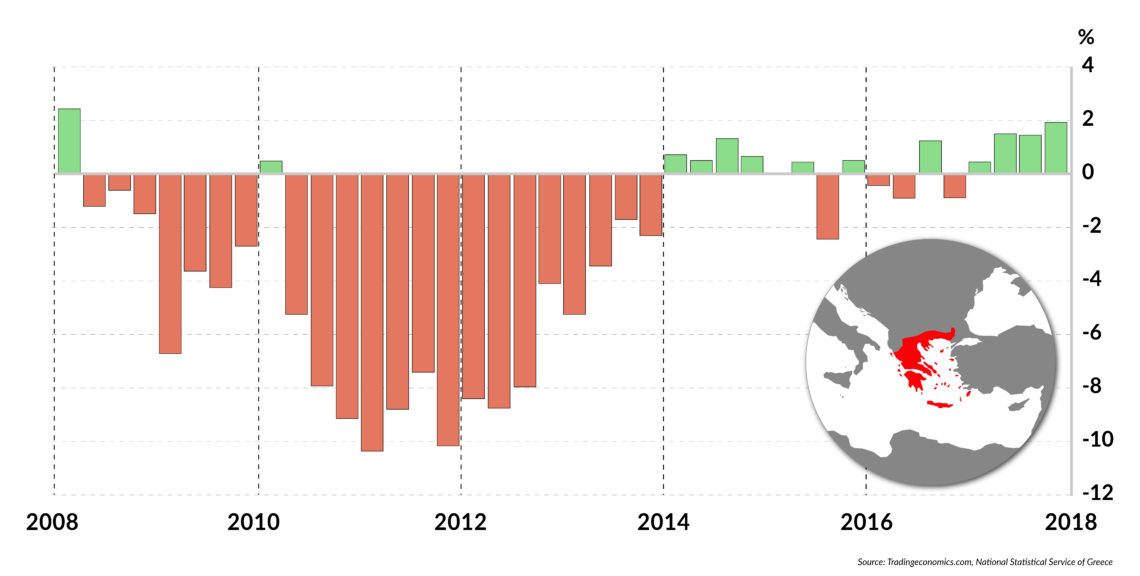

However, most observers believe that Greece is unable to meet its creditors’ requests. Some structural reforms have been implemented and the economy is no longer in tatters: it is currently growing at about 2 percent per year, business sentiment is picking up and the state budget features an overall surplus of some 0.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), including the cost of debt servicing.

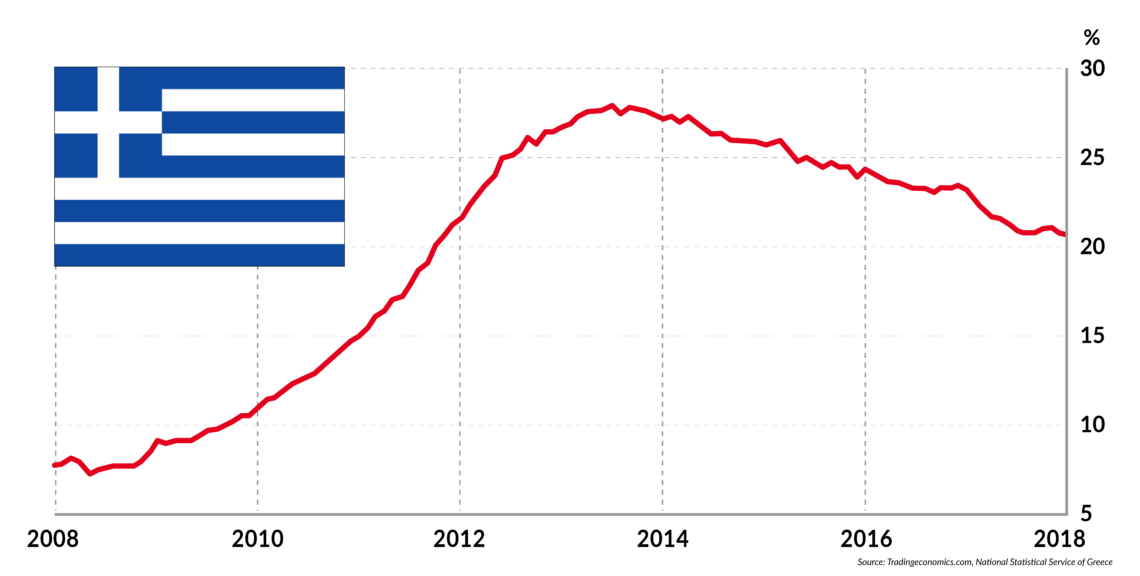

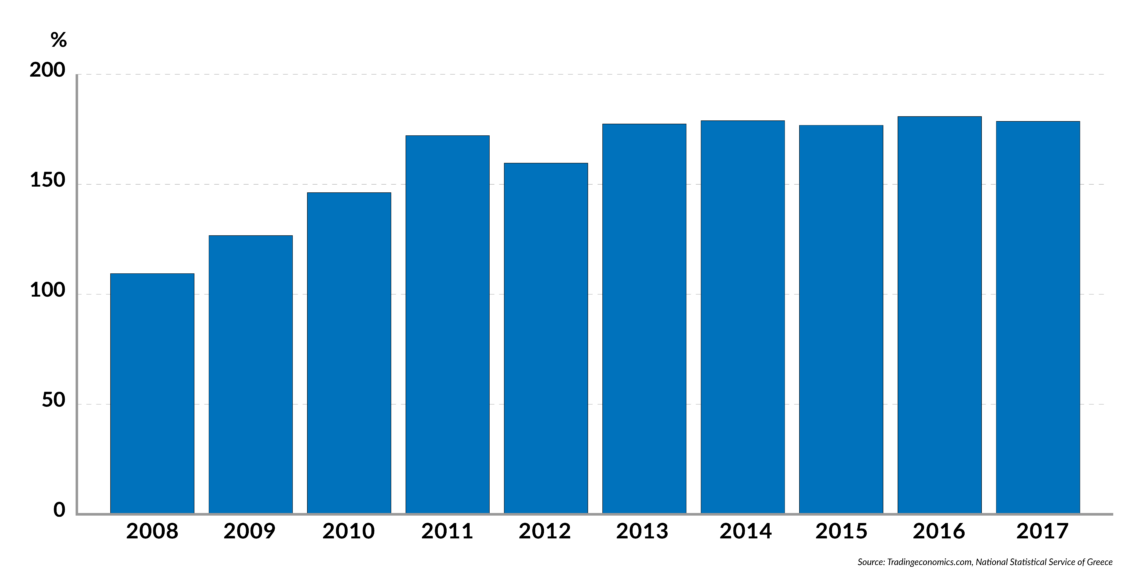

Yet, unemployment is still high (it is 20 percent of the labor force and 42 percent among the young), and a rapidly aging population means that the burden of state pensions on the budget will increase. If Greece had to refinance its debt by issuing new bonds in the absence of an international safety net, the interest rate the market might require could be high enough to rock the boat. Although the current interest rate on Greek government securities is relatively low – it ranges from 3 percent on 5-year bonds to 4 percent on 10-year bonds – the sheer size of the public debt (180 percent of GDP) and the lack of cheap bailout money would transform the current modest budget surplus into a spiraling deficit.

Debt forgiveness

While the Greek picture is far from exciting, it is not as dramatic as some would have it, and the scenarios for the future are not necessarily catastrophic. The Greek authorities have only taken some of the necessary steps. Much remains to be done. Nonetheless, the ball is now in the creditors’ court. The major players – the EU and the International Monetary Fund – have three options. They can take a hard line, pull the plug in August, and wait for the money Greece owes to them. A second possibility is that Greece’s creditors provide some sort of relief program, either by softening the terms of reimbursement or by making available additional resources that Athens would be allowed to tap should negative shocks occur. A third possibility would consist of forgiving the debt altogether and giving Greece a fresh start.

The IMF believes Greece will crash under the burden of its public debt even if all the required reforms are completed.

In January 2017, the IMF said that it believes Greece will crash under the burden of its public debt even if all the required reforms are completed. The economic justifications for that announcement are questionable, since the IMF assumed that Greece would be unable to sustain a significant primary budget surplus (i.e. before adding debt servicing to the bill). Nonetheless, the message from Washington was clear: Unless the Europeans are willing to remit the Greek debt, the IMF will no longer get involved in the Greek situation. In other words, Greece is a European problem in search for a European solution.

Of course, the commonsense solution would be unqualified debt cancellation. If one accepts that Greece is not able to reimburse its debt, forcing it to run significant primary surpluses would have three consequences. It would transform the reform process into a fight against the international community: even if Athens’ lawmakers succeeded in implementing further reforms, they would be perceived as an imposition from outside, rather than institutional changes that the Greeks have accepted and for which they carry responsibility.

Moreover, external pressures would weaken the government and create unnecessary tensions, which, in turn, would pave the way toward populism (general elections are due next year), questioning what has been done so far, and nipping recovery in the bud.

Finally, if the hard line prevailed, it would merely delay the date of the default, but would not avoid it. And it would also make things worse for Greece. Debt cancellation would relieve the Greeks from a heavy burden and make it easier (i.e. cheaper) for the Greeks to access financial markets. Default would lead to the opposite effect, since markets would see Athens as an unreliable borrower.

Facts & figures

Greece unemployment rate

Facts & figures

Greece debt-to-GDP ratio

Moral hazard

Will the happy-ending scenario come true? And will it actually be happy? There are two impediments to debt cancellation, neither of them insurmountable: accountability and reputation. In terms of accountability, for some eight years the international community has raised all sorts of difficulties before disbursing hundreds of billions of euros in bailout money. One could argue that this was necessary to ensure that Greece engaged in structural reforms. Yet, one might wonder whether governments and international organizations may squander taxpayers’ money to force other countries to carry out “desirable policymaking.”

Furthermore, debt forgiveness would bring grist to the mill of those who argued that the EU was not really interested in helping Greece to put its house in order, but rather in avoiding Grexit at a time when euroskepticism was rampant, and Grexit might have triggered the demise of the euro and fueled tensions throughout Europe.

Regarding reputation, forgiving the Greek debt might encourage other troubled countries to negotiate relief programs and/or special treatment, delay reforms and eventually hope to be pardoned once creditors ask for their money back.

Camouflaged relief

Since the euro is no longer in danger and Greece is no longer a priority, the EU authorities have no interest in transforming the post-bailout period into a renewed source of trouble. It is unlikely that Athens’ creditors will admit that the Greek affair was an attempt to mask the weakness of the euro (contrasting visions about the role of monetary policy within the eurozone) and to win consensus for the project.

If the scenario of camouflaged debt relief materializes, it will not mean the end of trouble for Greece.

However, it is equally unlikely that EU authorities will dig in and ignore compromise solutions. For example, they could refinance Greek debt by extending its maturity considerably and applying artificially low interest rates to the new debt. This would give Greece the breathing space it needs and would allow Brussels and Frankfurt to forget about Athens without losing face and without establishing a clear precedent for laxness. Brussels has announced that its experts will increasingly monitor the Greek government’s reform record. One should take this renewed interest as an exercise in face-saving, not an effort to bully the Greeks.

If the scenario of camouflaged debt relief materializes, it will not mean the end of trouble for Greece, where much remains to be done to stimulate economic recovery and stabilize the public finance situation. Privatizations are of course important. They strengthen competitive pressure, enhance revenues for the 2018 budget, and show that the Greek government is sticking to its commitments.

The key point, however, is whether Greece will be able to attract investments, both from home and abroad. These are badly needed. In 2017, investments were 11 percent of GDP – far too low for an economy that needs fast growth; and foreign direct investment remains weak.

High taxation, a relatively unskilled labor force, an inefficient judiciary and a heavy bureaucracy are still distinctive features of the Greek context. Fiscal discipline, privatization and debt relief will ensure that Greece stops being a problem for Europe. But Greece will need more to fully recover.