Zambia’s outlook after Hichilema’s election

The peaceful transfer of power in Zambia was a relief for its people and finances. Now the country’s new president, Hakainde Hichilema, has the tough task of repairing the economy, and he is counting on increased copper production to achieve that goal.

In a nutshell

- Democracy has prevailed in Zambia for now

- President Hichilema needs to kickstart the economy

- A surge in copper prices could help the country repay its debts

In Zambia, the peaceful transfer of power following August’s presidential election was met with surprise and relief. It followed a period of political tension when the government attempted to intimidate the opposition by banning protests and meetings, deploying the army and youth militias and blocking social media.

The defeated incumbent President Edgar Lungu claimed that the election had been neither free nor fair. That may be true, but the odds were stacked decidedly in his favor, not his opponent’s. Nevertheless, he conceded on August 16, under pressure from leaders of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Facts & figures

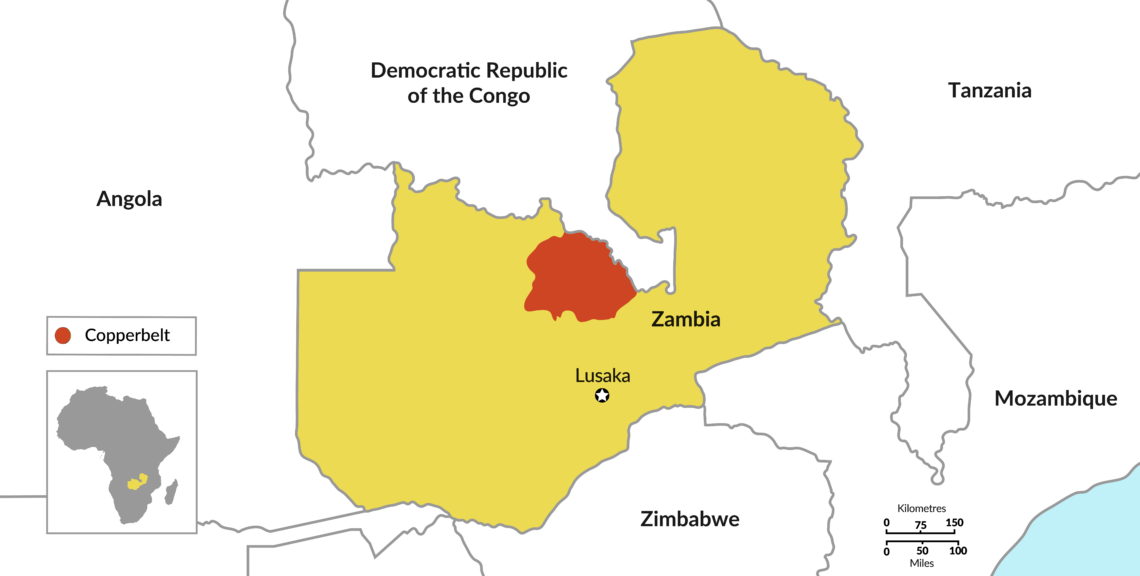

Zambia and the Copperbelt region

The slide toward authoritarianism in Zambia, considered one of Africa’s most stable democracies, had become a major concern for those interested in stability and the rule of law on the continent. For now, that slide seems to have been halted with the election of Hakainde Hichilema. However, commitment to democratic values will not be the critical factor in the new president’s success. Instead, it will be how quickly he can turn the economy around.

Political and economic deterioration

The 2021 campaign marked the sixth time Mr. Hichilema, a successful businessman, had run for president. This time he put himself forward as the leader of a broad coalition formed around the main opposition party, the United Party for National Development. The strategy helped him secure 60 percent of the vote. His decisive victory and the high voter turnout – some 70 percent – reflect the Zambian people’s dissatisfaction with the deterioration of their country’s democratic institutions and the acute economic crisis that unfolded under the previous administration.

President Lungu, leader of the Patriotic Front (PF) party, had come to power in 2011. Over the past decade, the PF resembled its Zimbabwean counterpart, Zanu-PF. Under Robert Mugabe, and now under President Emmerson Mnangagwa, Zanu-PF tried to consolidate executive power through constitutional amendments, used repressive measures against its critics and engaged in corruption. In 2018, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Finland and Sweden withheld aid to Zambia amid concerns over corruption and financial mismanagement.

In another similarity with Zimbabwe, Zambia’s PF party increasingly became intermingled with the state. The government tried to co-opt independent institutions, while public-sector jobs were distributed according to partisan loyalty. As in other southern African countries and in Latin America, resource nationalism in Zambia has seen a resurgence, primarily due to President Lungu’s attempt to shore up support in the country’s Copperbelt region.

Hichilema admitted that the state treasury is ‘literally empty.’

The previous administration also provides a cautionary tale against excessive public spending. After going through a painful restructuring process and having much of its debt forgiven under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, the Zambian economy entered a period of stability and robust growth. Its gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an average rate of 7.4 percent between 2005 and 2015. The 2014 fall in global commodity prices, however, interrupted that trend.

Despite a combination of slower economic expansion and higher debt servicing costs, the government maintained growth through high levels of public spending, engaging in large-scale infrastructure projects, many of them under China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Mining industry

President Hichilema, who recently admitted that the state treasury is “literally empty,” will have to find a way to revive a collapsing economy. Already struggling with structural challenges and overindebtedness, the financial fallout from Covid-19 proved a crushing blow: Zambia’s economy contracted by 4.9 percent in 2020, and the country became the first in Africa to default on its debt during the pandemic. In 2020, the debt-to-GDP ratio reached nearly 129 percent. It currently owes approximately $16 billion to external lenders. Under the 2021 budget, government operations and external debt consumed 94 percent of total revenue. In 2020, the country recorded an unemployment rate of 12.2 percent (its highest since 2010), while inflation reached 15.7 percent.

Considering all this, it seems clear that the mining sector will have to play a crucial role in the country’s economic recovery. Zambia is the second-largest copper producer in Africa, after the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with copper accounting for around 75 percent of the country’s export revenue and 10 percent of GDP.

In the late 1990s, the government privatized the country’s mining sector but kept a minority stake in the most important mines. In recent years, relations between the government and private investors have deteriorated due to rising resource nationalism and a volatile business environment. According to the Zambian Chamber of Mines, there was at least one tax change every 18 months between 2001 and 2018.

Facts & figures

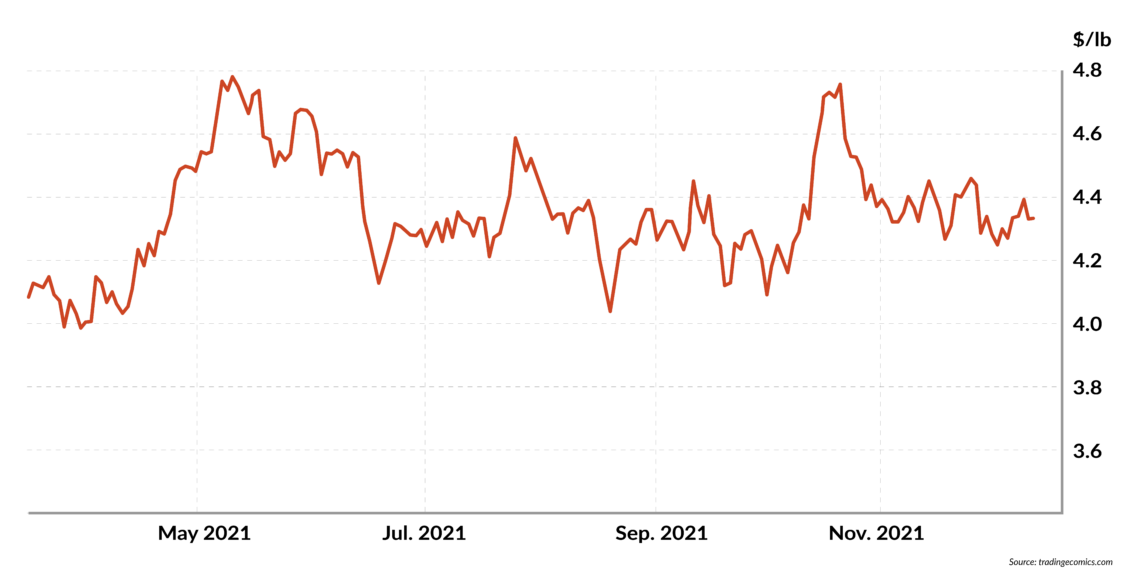

Copper prices ($/lb), 2021

In 2019, the government announced that it wanted to take a bigger role in the sector, further raising fees and taxes. At the same time, hostility toward private sector players and uncertainty in the industry were growing: Zambia owes its mining companies more than $1.2 billion in tax refunds. Last January, the government borrowed $1.5 billion to help the state-owned Zambia Copper Consolidated Mines take a majority stake in the Mopani Copper Mines from Anglo-Swiss mining company Glencore.

Copper prices have been volatile recently. After hitting an all-time high in May, they fell more than 15 percent by September due to fears that Chinese real estate conglomerate Evergrande could default on its debt. Weeks later, prices bounced back when it seemed the Chinese company might reach a deal with shareholders. As of this publication, the copper price is about 10 percent down off its May highs. Meanwhile, Zambia is positioning itself for a copper boom: output in 2020 neared 900,000 tons, a 13.6 percent increase from the previous year.

Difficult balance

Mr. Hichilema centered his campaign on fighting corruption and serving the people. But his administration will be judged by whether he fulfills his economic promises, including tackling the debt and achieving economic growth of 10 percent per year, all within five years.

President Lungu was expected to implement essential reforms and adopt a more market-friendly approach, but he never did. Unsurprisingly, creditors and investors were relieved when he lost the presidential race. Markets reacted with enthusiasm: after President Lungu conceded, Zambian bond prices reached their highest level in more than two years. The country’s currency, the kwacha, appreciated by 7.8 percent against the U.S. dollar.

However, the road toward recovery and growth is long and tortuous. To address the country’s debt problems and restructure the economy, President Hichilema needs outside help. His priority was to reach an agreement with the International Monetary Fund on debt restructuring – which he achieved on December 3. Once the IMF board gives its final approval in the first quarter of 2022, Zambia will have to begin renegotiating its debts with creditors. It will be a complicated task. Besides bilateral debt ($3.5 billion), creditors include Eurobond holders ($3 billion), multilateral lending agencies ($2.1 billion) and commercial banks ($2.9 billion). By estimates, China holds at least a quarter of the total debt, some of which was negotiated under opaque loan terms.

There is no escaping the necessity for painful reforms.

While President Hichilema’s victory will likely make negotiations with creditors easier, there is no escaping the necessity for painful reforms, including reducing public spending and increasing revenue. The government will have to implement unpopular measures like removing energy subsidies, cutting public sector wages and restructuring (or possibly privatizing) the state-owned electricity company ZESCO, which owes over $720 million to independent power producers.

Scenarios

Whereas the agreement with the IMF was crucial, it also represents an increase in Zambia’s overall debt volume by about $1.4 billion. To navigate the upcoming challenges, the new administration is counting on the political capital it gained from its election victory and, more importantly, on rising copper prices. Two scenarios should be considered.

Under a first and most likely scenario, Zambia will secure debt restructuring deals with its creditors. However, the government will be unable to avoid implementing austerity policies, leading to higher discontent in society. A weakened political opposition, combined with higher copper output and prices, will mitigate those effects.

Demand for copper is expected to outpace supply as its use in renewable energy technologies increases. Investment bank Goldman Sachs recently declared copper “the new oil” and predicted that prices for the metal could reach $15,000 per metric ton by 2025. If that were to happen, and if Zambia could achieve its recently announced production goal of 2 million tons by 2026, it would represent the best-case scenario for the country.

This scenario depends on the new government reaching an agreement with mining companies, particularly regarding royalties. As the world’s top two copper producers, Chile and Peru, go through periods of political uncertainty, Zambia, located closer to the fast-growing Asian markets hungry for the metal, could be in an advantageous position. It would just need a stable, investor-friendly framework.

Under a less likely scenario, President Hichilema’s reforms would run into tougher than expected political opposition in the short to medium term. At the same time, austerity would bite, while the positive effects of recovery and reform would take three to four years to materialize. A sudden cut in fuel and electricity subsidies, for example, would immediately take a financial toll on Zambian households. As recently seen in Kenya, such price hikes, with inflation rising for other goods and services worldwide, could trigger street protests.

There are also some risks in Zambia’s Copperbelt province. The region, which includes several key urban constituencies and is meant to become the engine of economic recovery, is – along with Lusaka – the epicenter of the country’s political life. One of former President Lungu’s strategies for remaining in power amid the crisis in the copper sector was to allow gangs of artisanal miners to occupy mine pits in exchange for electoral support. President Hichilema has promised to resolve these issues and regulate small-scale mining. However, balancing small miners’ claims with the interests of big companies operating in the region will remain a challenge.

A protracted crisis could also result from persistent volatility in the mining sector, which might deter new investors. If Chinese economic growth were to slow down significantly, it would dampen demand, putting pressure on copper prices and hindering Zambia’s recovery.