China in the public eye

Recent elections in the Indo-Pacific confirmed regional trends in balancing China and other regional centers of power, including most prominently, the U.S. Electoral outcomes in Australia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand indicate all will seek to maintain positive relations with Beijing with minimum impact on their ties to others.

In a nutshell

- Policy toward China was debated in the run-up to and during several Indo-Pacific elections

- China continues to be an important foreign policy and economic concern for Australia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand

- The region is confronted with a more assertive, China-focused American strategy that will have to be navigated without alienating China or the U.S.

This year, major elections took place in Australia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand. China was a recurring, if not predominant, topic in electoral campaigns. As a result, the contests and their outcomes shed critical light on the region’s future disposition toward the emerging regional power.

Australia

Elections in Australia unexpectedly brought to power a new Liberal-National coalition government with incumbent Prime Minister Scott Morrison at its head. Mr. Morrison is expected to make few changes in foreign policy. In fact, he has kept many ministers from his previous government in place, including the foreign and trade ministers appointed in 2018.

The prime minister and his government will have to continue to deal with China, which is still a critical economic partner although it presents serious security concerns. This challenge was made clear during the campaign. It took place against the backdrop of several China-related developments: Australia’s decision to bar Chinese telecommunications from its 5G network; the rush of legislative activity to stem Chinese domestic political influence; the year-long (2017-2018) Chinese freeze on relations with Australia; and reports of Chinese restrictions on Australian coal exports (Australia currently exports about a quarter of its coal to China).

As Australia’s economy slows, pro-China voices will gain influence.

These conversations intensified an ongoing debate over Australia’s geostrategic positioning. Prominent political figures and scholars made use of this tension with China to argue that Australia ought to distance itself from its traditional alliance with the United States. However, this is a minority view and the new government is highly unlikely to take this path. It will rather continue making common cause with the U.S. on security and political issues relating to China. For instance, both governments have criticized Beijing’s treatment of Uighurs, a Muslim minority in the Xinjiang province. On August 1, Australia and the U.S. – along with Japan – issued a ministerial statement expressing concern about Chinese activity in the South China Sea. The two countries also recently held their 29th annual bilateral security consultations (AUSMIN), which seek to align priorities and alliance activity across a broad range of shared interests.

Yet appeals for a more China-friendly approach will remain prominent in Australian political discourse. Many in the Australian policy community credit the country’s 28-year recession-free record and, particularly, its immunity to the 2008 global financial crisis, to its expanding trade with China. As Australia’s economy slows and faces prospects of recession over the next year, pro-China voices will gain influence.

The traditional convergence between the two major Australian political parties on foreign policy notwithstanding, the close margins in parliament will tempt the Labor party to heed the friendly camp and expand on the constructive approach to China they laid out during the elections. This will, in turn, give the Morrison government less room to maneuver, whatever its natural inclinations toward China. This was already seen in August, when Australia refused to consider hosting American intermediate-range conventional missiles.

India

This year, Indian elections resulted in a resounding victory for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi. India has traditionally been very careful in its dealings with China. The countries share an unsettled land border and New Delhi is intensely wary of China’s close relationship with Pakistan. There is also some discomfort around the growing Chinese economic, diplomatic, and military reach into the Indian Ocean. That said, Prime Minister Modi has been more willing than his predecessors to take risks. For example, his government was the first major country to express reservations over the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – primarily due to an important role offered to Pakistan in the initiative. Also, in 2017, Mr. Modi pressed China and prevailed in a border standoff over Doklam, the northeast tri-border region both countries share with Bhutan.

The Indian prime minister has sought to buffer some of the risk associated with his assertive approach to China by tightening his relationship with the U.S. However, Delhi-Washington relations are suddenly under strain because of trade issues and third-party sanctions on Iran and Russia.

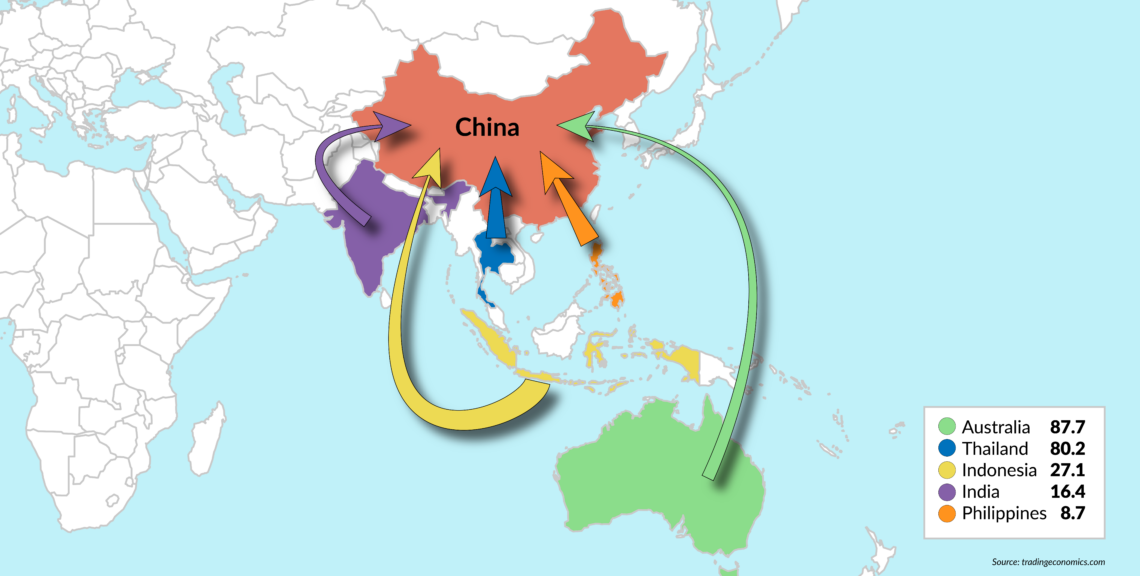

Facts & figures

Indo-Pacific trade with China

Exports of goods to China in 2018 (billions of USD)

Under these circumstances, the Indian government could seek closer ties with Russia, with which it has a very long, but currently dwindling, security relationship. This, however, would further worsen the country’s relations with the U.S. Alternatively, it could attempt to improve relations with China – which would require an unlikely effort by Beijing to address Indian concerns regarding its northern border and the China-Pakistan relationship.

India will most likely look for cosmetic solutions to its issues with China while trying to smooth over its troubles with the U.S. Over the last 20 years, India and the U.S. have demonstrated a strategic interest in maintaining positive, expanding relations. The realities driving this goodwill – largely concerns about China’s rise – remain. A fundamental shift is very unlikely. The real variables are how the Trump administration will handle matters at the heart of China-U.S. relations, and the disposition of an eventual new U.S. administration in 2021.

Indonesia

In April, Indonesia elected a president and a vice president, as well as members for its bicameral national legislature and local administration. In all, elections for more than 20,000 offices were held. The incumbent president, Joko Widodo (Jokowi), was reelected with a new running mate, Muslim cleric Ma’ruf Amin. As in most bids for reelection, much of the campaign focused on Mr. Jokowi’s performance. His record on poverty reduction and infrastructure was under significant scrutiny. On the former, the electorate gave him good marks, but the latter is directly linked to China – a uniquely sensitive issue in Indonesia.

Unlike many other countries, Indonesia’s attitude toward China is not defined by geopolitical or territorial tension. Conflicting claims in the South China Sea are largely dormant. Yet, China is a sensitive issue for Indonesians because of the country’s painful history with its ethnic Chinese minority. Over the last decades, anti-Chinese sentiment led to pogroms, official discrimination and especially brutal violence in 1965-66, when as many as half a million people were killed in the name of anti-communism. Mr. Jokowi’s political opponents purposely tapped into these powerful associations by characterizing the president’s effort to attract infrastructure investment from China as a betrayal of Indonesian national interests.

Chinese influence will grow, but only as far as Jakarta will allow.

By way of contrast, Mr. Jokowi’s presidential rival, Prabowo Subianto, vowed to review Chinese investments in Indonesia. His defeat spared China the worst-case scenario. Indonesia will continue to find ways to facilitate Chinese investments. As a result, Chinese influence will grow, but only as far as Jakarta, with its fierce interest in autonomy and distinctive sensitivities, will allow.

The Philippines

The Philippines did not hold elections for its chief executive; it held mid-term elections for half of its Senate and all of the seats in its house of representatives. Nevertheless, the May 13 balloting offered an unambiguous endorsement of President Rodrigo Duterte’s domestic policies and implicit acquiescence to his conciliatory approach toward China.

In the Philippines, party affiliation is mutable and gravitates toward the occupant of the presidential office. Officials can turn suddenly against a president who runs into political trouble. Mr. Duterte, despite his outrageous comments, the liberties he has taken with the rule of law and a drug war in which thousands were executed without trial, has not experienced such desertion: he remains extremely popular. His support was a much-prized campaign asset and the legislators he supported won. As a result, the politicians who control Congress are in his debt.

The Duterte government will continue to expand relations with China.

President Duterte’s controversial approach to China since he came to power three years ago was discussed during the elections because of a flare-up involving Chinese paramilitary fishing vessels around the Philippine-held and populated Thitu Island (Pag-asa in Tagalog) in the South China Sea. However, the incident did not impact the election, partly because the Duterte administration has settled into a more stable relationship with the U. S., and partly because of his warnings to the Chinese over the event. The issue had limited influence; although voters did care about it, they were more motivated by matters relating to their day-to-day well-being.

The Duterte government will continue to expand the country’s relations with China, as long as Beijing shows some respect for the Philippines’ claims in the South China Sea and delivers on its promises of investment. Even if uncomfortable incidents occasionally occur – like the continued paramilitary activity around Thitu or the June 9 sinking of a Philippine boat – the president’s fresh mandate will allow him to bluster through and stay on course in his attempt to rebalance relationships with the U.S. and China. (The problem with Chinese fishing vessels swarming Thitu Island also continues.)

Thailand

In Thailand, the 2014 coup leader and incumbent Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha won the election and formed a new government despite the fact that his party did not win the most constituencies. The party who did is a populist faction with ties to former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra – a destabilizing (if, to some, democratic) presence who perpetually hangs over Thai politics. By virtue of a new constitution designed specifically to prevent a Thaksin-linked party from reaching power again, General Prayuth was able to cobble together a slight majority in the lower house and dominate the military-appointed upper house. Because the houses elect the prime minister jointly, Gen. Prayuth easily won. There is no question that the elections were rigged in his favor. Still, judging by the extent of horse-trading necessary to secure a narrow majority in the lower house (which includes 19 parties) and to select a cabinet, the government will have to pay politics greater heed in the future.

Although the internal tension is unlikely to affect the country’s policy toward China, the imperfect return to democracy will allow Bangkok to improve relations with the U.S. This could serve as a hedge against China in the short term. In the longer term, the problem with U.S.-Thai relations lies in the variability of the U.S. commitment. Thai politics are far from settled; Washington’s reactions to the coups in 2006 and 2014 showed the impact of this instability on relations between the two countries. This strategic drift away from the U.S. will therefore continue, although perhaps more slowly. This will keep the door open to a continuing, deepening relationship with China. Since Thailand needs additional support for its autonomy, it will depend on ASEAN and reach out to Japan. For example, Thailand could decide to join the Japan-led, 11-nation Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Warming relations with Thailand represents China’s most significant foreign policy opportunity in Southeast Asia. This rapprochement is not always in the headlines, possibly because it has already progressed so far, but Thailand is less hampered by its ties to the U.S. than the Philippines. China will be a willing and patient partner in Thailand’s strategic evolution.

Scenarios

China’s inexorable rise is the most salient major feature of the Indo-Pacific’s geopolitical environment. In democratic countries – even those like Thailand with the most constrained politics – how they deal with this challenge plays across elections. The most recent confirm ongoing trends.