Inflation ripples across the U.S. and global defense communities

As high price inflation crimps the Pentagon’s purchasing power, lawmakers and policymakers are scrambling to meet the elevated security needs.

In a nutshell

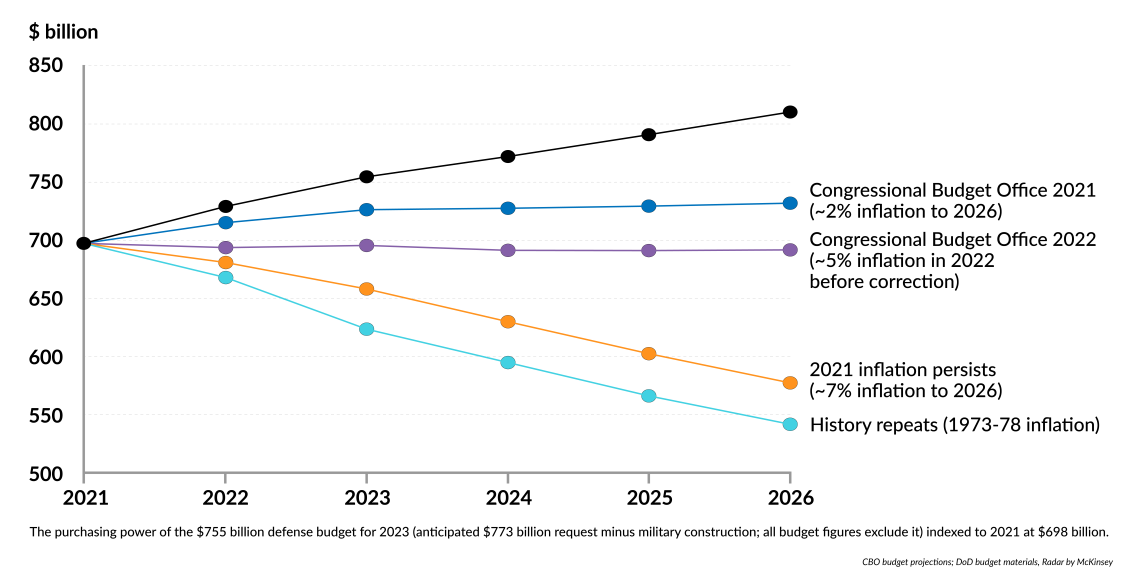

- Hundreds of billions of dollars in Pentagon buying power is at risk

- Inflation also threatens to impair security enhancement in Europe and Asia

- Whether Congress will sign off on additional defense funding is unclear

The defense world’s financial outlook has darkened. Prices continue to inflate, slowing economic growth and exacerbating supply chain shortages exactly when Russia’s war on Ukraine and tensions with China over Taiwan are increasing the need for an arms buildup.

Washington, which is already running record fiscal deficits and seeing increased partisan rancor, will struggle to reconcile spiraling costs and shortages with higher demands for security spending. What is happening in the United States mirrors and impacts the scramble in Europe, Asia and the Middle East to fund and find the arms and ammunition to enhance national defense capabilities.

Prices and geopolitics

A recent assessment from the Pew Research Center finds that the world’s 44 most advanced economies are nearly all seeing a spike in inflation. Consumer prices have risen substantially since before the Covid-19 pandemic; Turkey has the highest level of inflation, with over 50 percent, and the U.S. inflation rate was above 9 percent in June (1.4 percent in 2020).

In the U.S., inflation was fueled in part by massive federal spending by the administration of President Joe Biden. That expansion, however, did not include dramatic increases for the Department of Defense (DOD). Indeed, upon entering office, the administration envisioned a relatively flat military budget. Mr. Biden anticipated Pentagon needs would decline because his administration’s foreign policy approach assumed more restraint in overseas activities. In addition to withdrawing from Afghanistan, the administration expected that a new nuclear deal with Iran would reduce demand for forces in the Middle East and that the U.S. would also find some measure of detente with Russia and China. None of those expectations have played out in practice.

Congress has signaled a strong desire to increase military spending, particularly to counter China and Russia.

Rather than declining needs for military hardware and troops, the U.S. is experiencing the opposite. For instance, in May 2022, the U.S. Congress approved a $40 billion-aid package for Ukraine, which included $20.1 billion in direct military aid. The U.S. also sees spiking manpower costs, as all the services are missing recruiting goals. The U.S. Army, for example, has had to offer significant new financial incentives to attract recruits to join the force. Further, Congress has signaled a strong desire to increase military spending, particularly to counter China and Russia.

Budget in the crosshairs

The rapidly escalating demand for increased security investment has collided head-on with the administration’s defense planning effort, which did not anticipate the rapid rise in inflation – the president’s initial annual budget proposal for 2023 forecast inflation at 2.3 percent. Inflation is already running at three times that. Across the defense department, from fuel to personnel costs, inflation may not be running that high, but the rate for military expenditures is certainly already much higher than 2.3 percent.

Aside from all that, the impact of inflation has further inflamed partisan tensions in Congress. For instance, Senate Armed Services Committee Ranking Member James Inhofe complained, “[m]ost problematic is that this budget neglects to sufficiently account for historic inflation.”

Historically, prices for the goods that the Pentagon acquires tend to rise at a rate higher than the consumer price index (CPI) for urban wage earners and clerical workers – on average, 20 basis points higher.

Facts & figures

How inflation could reduce the Pentagon’s buying power, scenarios

There is no question that the national defense sector is facing a resourcing squeeze when there is a demand for more resources. Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks has already stated that the Pentagon would need to come back with a supplemental request to make ends meet. Further, the administration has already hinted at a potential supplemental budget request to support Ukraine.

Also, to consider is the increasing partisan acrimony over how the Biden administration manages the Pentagon. Many conservative members are frustrated by what they see as spending on left-wing political projects, including “green” energy programs, diversity programs, and controversial “social and cultural” priorities.

Whether a divided Congress will sign off on all this additional funding remains uncertain. As Heritage Foundation defense analyst Fred Bartels correctly predicted in late 2021, “[a]s long as inflation persists at its current elevated level, it will have a substantial impact on the Pentagon and its management of the armed forces.”

The arms race

Spiraling inflation coincides with rising demand for arms and ammunition for U.S. forces and allies responding to increasing geopolitical uncertainty in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. For example, the U.S. defense company Raytheon Technologies must build a new production facility to meet the long-term demand for stinger antiaircraft missiles from NATO partners.

The challenge is complicated by increasing costs, worker and supply chain shortages and the appreciation of the U.S. dollar, which makes foreign purchases more expensive. That has prompted many nations to look for new suppliers rather than just relying on the U.S. defense industry. Poland, for example, will likely purchase new tanks and self-propelled artillery from South Korea because its defense companies promise to make deliveries three years earlier than the Americans.

In the near term, fiscal pressure on defense will likely persist.

Competition to acquire arms and ammunition is likely to ripple across the globe. Russia, for instance, is a major global arms supplier but will be forced to divert much of its production capacity to rearm forces depleted in the war against Ukraine. That will leave fewer products available for export. Further, Russia is also facing supply-chain shortages from global competition and the burden of widespread sanctions.

Scenarios

In the U.S., the most likely scenario is that Congress will find a way to fund short-term needs but also move to deliver additional budget management authorities. That will include reprogramming authorizations and applying targeted changes to the president’s budget request. Congress could also put more emphasis on multiyear appropriations in crucial programs. Also, a future Republican-controlled Congress would more likely put pressure to trim ineffective programs and misguided spending, such as the F-15EX program, and move to block what the Republicans regard as “politicized” spending at the Pentagon.

However, “[a]t its core,” Mr. Bartels, the security analyst, notes, “inflation is a problem for the whole economy, and that cannot be fully mitigated at the DOD.” In the near term, the political divide over managing the U.S. economy will not likely abate, and thus, fiscal pressure on the defense department will likely persist.