Rethinking the link between demography and inflation

Two economists make a strong argument that inflation is tied to China’s demographics, implying that it could stick around for years to come.

In a nutshell

- “Secular stagnation” has become the default theory for the cause of slow growth

- The Fed and ECB disagree over how big a threat inflation is

- Price movements may be tied to China’s demographics

Are we about to experience a reversal of macroeconomic megatrends? Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, in their book “The Great Demographic Reversal,” published in August 2020, claim we are.

Demographic shifts, such as the aging of populations in the Western world, and now also in China, will revive inflationary pressures in the decades to come, the two British economists predict.

Predicting inflation

Back in June 2016, they presented a preliminary view of their study at a conference of the Bank for International Settlements. Three and a half years before the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in Wuhan, however, their scenario of a demographically-induced pickup in global inflation fell on deaf ears.

Back then, nearly all economic projections anticipated a demography-driven slowdown in inflation. At the time, the phrase on most analysts’ and policymakers’ lips was “secular stagnation” – a concept brought into fashion in 2013 by former United States Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers. The latter had borrowed it from a long-discredited economic theory of the late 1930s, whose purpose was to make sense of “sick recoveries which die in their infancy and depressions which feed on themselves.”

The revived secular stagnation model rapidly went mainstream in contemporary macroeconomics. One reason for its success was that it provided a ready-made answer to the tricky question as to why – despite central banks’ unprecedentedly vast interventions to fight the Great Recession – our advanced economies would not get better. Because of deep-running structural changes, secular stagnation theorists argue, industrialized countries will remain stuck in a trap of chronically low growth, low interest rates and near-zero inflation.

Demography as destiny

The aging baby boomers are commonly branded as the number one culprit for this situation. In the U.S., they will all be over 65 by 2030. In Europe, the ratio of young to old is expected to be 1:2 in 2060 (in comparison to 3:1 in 1960).

According to this perspective, demography will seal the fate of Western societies first because an aging population means falling productivity and higher fiscal costs. As the public debt burden reaches a crescendo, age-related healthcare and pension expenditures could quickly become unsustainable. In one case or another, this will weigh heavily on economic growth.

Secular stagnation theorists argue that industrialized countries will remain stuck in a trap of near-zero inflation.

It is also stated that these demographic developments have led to an excess of saving over investment and an insufficient level of aggregate demand. This is allegedly what pushed interest rates down. The global financial crisis exacerbated the problem, but in no way caused it. The decline of real interest rates had begun in the 1980s – long before central banks were forced to cut short-term nominal interest rates to zero or even slightly below.

In an International Monetary Fund (IMF) publication of March 2020, Mr. Summers further explained that, in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, difficulties in absorbing the “savings glut” made it increasingly harder for central banks to lift inflation up to their targets. Whatever they were doing, the downward trend of inflation appeared unstoppable.

Lower for longer

The coronavirus emergency, at least in its early stages, was generally presented as another massive global shock increasing the prospects of the “low-for-long scenario” – making it “even lower for even longer,” as described in a June 2021 report by the European Systemic Risk Board.

During the Great Lockdown of spring 2020, prominent secular stagnation theorists predicted that deflation – not just sustained disinflation – was our economic future.

Among them was former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard, who predicted there was less than a 3 percent chance that inflation would heat up due to the health crisis.

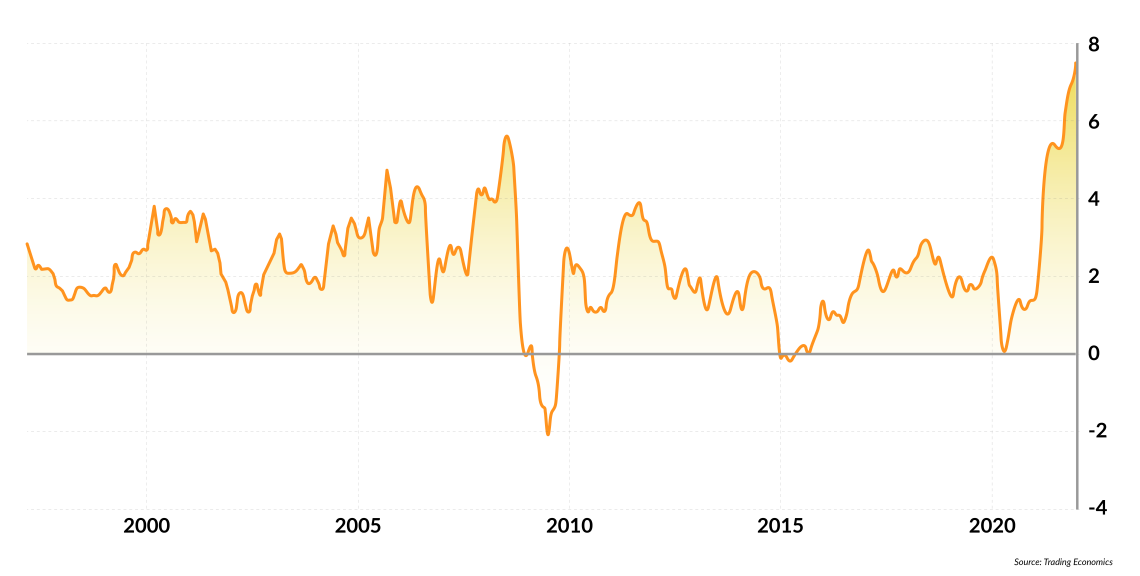

U.S. inflation rate (%), 1997-2022

One year later, however, against all predictions, inflation picked up strongly. In the U.S., by year-end, it had accelerated to 7 percent. In the eurozone, it hit a record high of 5 percent.

Such annual inflation rates had not been seen in decades. All of a sudden, the calamity of the Great Inflation of 1965-1982 was back on economists’ minds.

Summers’ reversal

Interestingly, among the first to raise the alarm were Messrs. Summers and Blanchard. Since early 2021, both have been leading voices in America’s “Great Overheating Debate.” They warned that an unreasonably oversized fiscal and monetary stimulus could soon cause the U.S. economy to run too hot and prices spiral out of control.

In an opinion piece published in The Washington Post in November 2021, Mr. Summers openly distanced himself from his former views on macroeconomic policy, evoking a saying attributed to John Maynard Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind, do you?”

When such elite economists start to predict that there could be structurally high inflation in future years or decades, does that imply the secular stagnation narrative has outlived its relevance?

The European Central Bank (ECB), on the other hand, continues to predict that disinflationary forces are here to stay.

It seems not. A puzzling disagreement has recently emerged among policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic over how to interpret the current inflationary episode.

Concerned that inflation expectations might become entrenched, the U.S. Federal Reserve decided last December to reverse its monetary policy. It announced tightening on three fronts. Not only will asset purchases be tapered and interest rates raised; the Fed also began preparing to shrink its gigantic balance sheet.

Great denial

The European Central Bank (ECB), on the other hand, continues to predict that disinflationary forces are here to stay. Inflation is perceived essentially as a “temporary” (i.e. pandemic-driven) phenomenon. Near-term factors, such as higher demand, supply bottlenecks or labor market friction in the context of a reopening economy, as well as skyrocketing energy prices, will melt away as soon as the “pandemic cycle” comes to an end, Europe’s monetary authority is convinced. Such relative price shocks – affecting some sectors more than others (housing, food, transport, etc.) – should not be confused with a trend change, policymakers say.

The ECB expects prices to decrease sharply later this year. According to its latest forecasts, euro area inflation will stabilize at 3.2 percent in 2022, before subsiding to significantly below the 2 percent inflation target in 2023 and 2024.

Given these expectations, the criteria for withdrawing stimulus or raising interest rates are “not in place,” ECB chief economist Philip Lane said in a recent interview. The forces that had generated too-low inflation before the pandemic, he said, will manifest themselves again afterward. The conclusion is that even under the current circumstances, policies of massive monetary expansion remain fully “relevant.”

But what if Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan are right, and the eurozone has to deal with persistently higher inflation in the years to come? Would such policies then still be tenable?

Disinflation shock

The two economists identified three inflection points in inflation’s long-term trajectory.

In previous centuries, global inflation, inflation expectations and interest rates have generally been relatively stable. Then, around 1950, these indicators all picked up dramatically. After peaking in the late 1970s, they began to fall just as abruptly, until the extremely low levels observed in recent times were reached. Over the past year, however, another trend shift appears to be taking place, even if the major central banks, including the ECB, remain largely in denial about the rebound in inflation.

What have been the driving forces behind the disinflationary trend of the past decades? And why should it end now?

Facts & figures

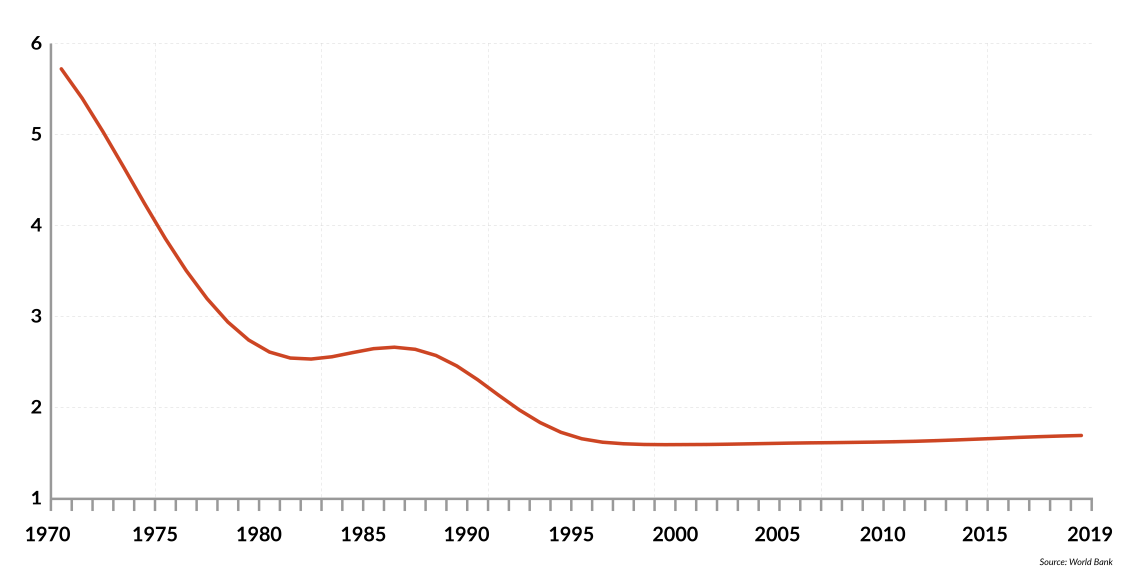

China fertility rate (total births per woman)

To both questions, the duo provides an explanation refuting the mainstream claim that inflation (or disinflation) is essentially a “monetary phenomenon” to be dealt with by central banks.

In response to the first question, they argue that over the past 40 years it was above all China that disinflated the world by producing and inundating global markets with cheap goods. Favorable demographics provided the country with a huge and rapidly growing labor force willing to work hard for low wages. China’s inclusion in the world’s production and trading networks ended up affecting labor markets in advanced economies as well. In the years leading up to hyper-globalization, Western companies were eager to offshore their production to Asia (and to a lesser extent to Eastern Europe) in order to profit from these areas’ low labor costs.

According to Goodhart and Pradhan, this shift of production led to a weakening in labor bargaining power and, ultimately, to stagnating wages in the West. These trends coincided with the period when, on our side of the world, baby boomers joined the workforce en masse, putting even more downward pressure on wages and prices.

Inflation revival

To the question of why inflation is bouncing back now, Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan again cite China’s demographics as the answer.

Firstly, the size of the working age Chinese population has started to shrink, and this trend will intensify in the years ahead. At the same time, the ranks of the elderly keep swelling. No other nation in the world is aging at the speed and scale of China.

The one-child policy, implemented between 1980 and 2015, exacerbates the country’s demographic reversal. Over the past three decades, this brutal population-planning initiative had led to a strong fall in the child-dependency ratio. Today, it is the old-age dependency ratio that is increasing just as sharply.

In the decades to come, the graying of China will put both its support systems for the elderly under enormous pressure.

“A larger share of dependent population is inflationary, whereas a larger share of working age population is disinflationary.” This is the conclusion Mikael Juselius and Elod Takats came to when studying the repercussions of population age structure on the inflation paths of 22 countries between 1870 and 2016. Their finding became a cornerstone of Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan’s work.

In the decades to come, the graying of China will put both its private and public support systems for the elderly under enormous pressure. Unseen fiscal challenges are brewing. Moreover, the continuing fall in birth rates will crimp the country’s growth prospects, leading to labor shortages and a rise in the bargaining power of labor relative to capital. Workers, who are also more highly educated than those of previous generations, will demand higher pay.

For Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, the era in which China drove output up and inflation down in the West is over. From now on, they say, it will be doing the opposite.

In the meantime, on our side of the world, baby boomers are preparing to retire – yet another inflation driver in advanced economies, according to Messrs. Juselius and Takats.

Finally, Messrs. Goodhart and Pradhan predict that our aging societies will experience a fall in savings, an increase in investments and, ultimately, higher real interest rates. These developments, once again, contradict the secular stagnation theory.

Corroborating factors

The authors focus primarily on inflation’s ties to demographic factors. However, their predictions appear to be corroborated by non-demographic factors as well. Among those worth mentioning are the rising economic and geopolitical tensions between China and the West.

Today, U.S. and European industries are struggling to keep pace with Chinese manufacturers – some of whom control entire supply chains in sectors of strategic importance for the future (such as the production of batteries for electric cars). The U.S. is particularly determined to free itself from its strong technological dependency on China. The path to technological self-reliance, however, will be long and cost-intensive. Moreover, many Western companies that once chose to offshore their operations to China are now bringing manufacturing back home – even if this entails higher costs and smaller margins. Backshoring and production relocation could become significant inflationary forces in the near future.

So could the green transition. Even ECB executive board member Isabel Schnabel recently acknowledged that energy price inflation might prove far “more persistent than currently anticipated.”

In all these cases, difficult policy choices lie ahead of central banks.

One may agree or disagree with the Goodhart-Pradhan global approach to inflation. But the governor of the Bank of Finland, Olli Rehn, is right to observe that – whatever its level of accuracy – their work serves to “invite, even force, reflection on widely held assumptions” about future developments.

As a member of the ECB’s Governing Council, Mr. Rehn might have the opportunity to ensure the voices of these two veteran macroeconomists are heard when policymakers decide on Europe’s monetary stance over the next few months.