Iran’s decision makers

With the recent focus on Iran-West tensions, it is worth considering who exactly the decision makers are in Iran’s highly complex structure of power. While Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei holds tremendous sway over the future of Iran, he is not all-powerful.

In a nutshell

- Iran’s regime comprises a complex group of stakeholders

- The supreme leader consults the IRGC on major decisions

- Young people are becoming increasingly disenchanted

This new series of GIS reports examines how effectively countries are ruled and the consequences of governing systems for economies, societies and nations’ development prospects.

This report is the first in a three-part series on Iran from GIS Expert Professor Dr. Amatzia Baram. The next two, due to publish in the coming weeks, focus on Iran’s scenarios for change and its strengths and weaknesses.

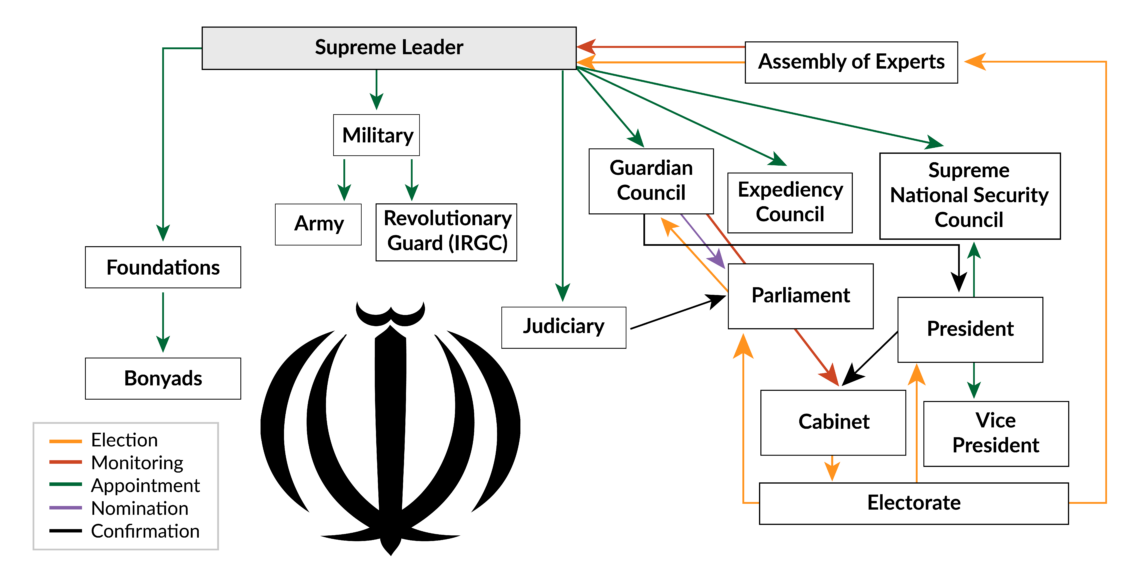

Though Iran is nominally a republic and widely considered an authoritarian regime, its power structure is highly intricate. With the recent focus on Iran-West tensions, the domestic protests, its economic struggles and discussion of potential regime change, it is worth considering who exactly the decision makers are in Iran and whom the current system benefits. While Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei holds tremendous power, it is not unlimited. There are several other players exercising various degrees of influence. Understanding their roles can offer a clearer picture of where the regime stands and how strong its hold on power really is.

Supreme leader

The single most powerful decision maker in Iran is Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. His constitutional position is supreme leader (rahbar), but more importantly it is his position according to the late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s political theory of the Governance of the Islamic Jurist (Wilayat al-Faqih). A senior cleric must always fill this role. The supreme leader is the chief commander of the Iranian Armed Forces. All decisions by the president and his government must be approved by the supreme leader. Since 1979, when the Islamic Republic was born, no major socioeconomic, security or foreign policy decision has been made without his consent.

Mr. Khamenei hates and fears the United States, which he will never be able to trust.

This was the case even when Ayatollah Khomeini was very ill and weak, and is also the case now, with Ayatollah Khamenei old and ailing. Mr. Khamenei hates and fears the United States, which he will never be able to trust. However, when he reached the conclusion that the regime would be in danger if he did not approve of the 2015 nuclear agreement, he authorized the president and the foreign minister to sign it.

If there ever was a real semi-independent foreign minister in Iran, it was the late Major General Qassem Soleimani, commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Having the easiest access to Mr. Khamenei’s ear, his influence over security and foreign policy was second to none. Their collective power notwithstanding, there is no group of clerics who could oppose Ayatollah Khamenei’s decisions.

According to the constitution, the supreme leader may be removed – but this has never happened. The constitutional body that has the formal power to remove him and the many institutions behind it have been content with the prestige and immense economic benefits they enjoy in the existing system and have left grand policy largely to him. A coalition of clerics that tries to remove the supreme leader would form only if it was clear that the regime is close to falling. Still, even then the clerics would have to be convinced that by sacrificing him they can save the system. An internal schism would only hasten the regime’s downfall.

Facts & figures

Governance in Iran

Iran is a theocratic republic, with 31 provinces. The current system dates back to April 1, 1979, when it was declared the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Executive branch

- The supreme leader is the chief of state, while the president is head of government. The supreme leader is appointed for life by the Assembly of Experts. The president is directly elected by an absolute majority popular vote in two rounds if needed for a four-year term (eligible for a second term and an additional nonconsecutive term). The cabinet is the Council of Ministers. It is selected by the president with legislative approval. The supreme leader has some control over appointments to several ministries

Legislative branch

- The Islamic Consultative Assembly is unicameral, with 290 seats. Voters directly elect 285 members in single- and multi-seat constituencies by a two-round vote. One seat each is reserved for Zoroastrians, Jews, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, Armenians in the north of the country and Armenians in the south. Members serve four-year terms. All candidates to the parliament must be approved by the Council of Guardians

Judicial branch

- Iran’s highest court is the Supreme Court. Its president is appointed by the head of the High Judicial Council (HJC) – a five-member body which includes the Supreme Court chief justice, the prosecutor general, and three clergy – in consultation with judges of the Supreme Court. The president is appointed for a single, renewable five-year term

- Subordinate courts include the Penal Courts I and II, Islamic Revolutionary Courts, Courts of Peace, Special Clerical Court (which functions outside the judicial system and handles cases involving clerics) and military courts

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

According to the constitution, the Revolutionary Guards (also known as the IRGC or Pasdaran) are “the guardians of the revolution.” This means that they are designed to protect the regime from its domestic enemies and foreign conspiracies. In reality, they are far more than that. They cannot single-handedly decide about security, foreign, social, cultural, political and economic policy, let alone remove or anoint the supreme leader, but their input is equal to, if not weightier than, that of the senior clerics. Both their great expansion and prestige were the result of their heroism in stopping the invading Iraqi forces in 1980 and pushing them back later. At the time, their commanders provided an inspiring example by charging at the head of their troops, dying in droves. Today the IRGC has lost much of its shine, since it is partially blamed for the failures of the economy.

Facts & figures

The IRGC is a combined arms force with its own ground forces, navy, air force (which accidentally shot down the Ukrainian passenger jet on January 8, 2020) and intelligence service. They number 125,000. They also control the Basij militia, a volunteer-based force, with 90,000 regular soldiers and 300,000 reservists. They are also in charge of Iran’s nuclear and missile projects.

The Pasdaran control at least 10 percent and, according to various sources, 30 percent or more of Iran’s economy. Their annual revenue from those assets is believed to be more than $12 billion. They receive many government no-bid contracts to build and manage infrastructure including bridges and dams, as well as petrochemical and communications installations. Furthermore, they control several large charitable trusts known as bonyads. All bonyads are tax-exempt and have no obligation to report to government authorities. They are all run by clerics, but a large share of them belong to the Pasdaran. In addition to their business revenues, all bonyads receive government funds and some of them are involved in the black market.

The present commander of the IRGC is General Hossein Salami, who is more of a hardliner than his predecessor Mohammad Ali Jafari. The Pasdaran has a political front that supports them, the Abadgaran. Veterans of the Revolutionary Guard may be found in parliament, in the government and in senior positions of the civil service, including in the foreign service as senior diplomats. Their formidable military machine can compete with the army. Indeed, they are designed to prevent or counter any military attempt at a coup d’etat.

The IRGC’s influence reaches into all parts of the Iranian system. Its members do not necessarily share the same political views: some are in favor of meaningful changes like opening up the economic system and allowing more cultural freedom (in terms of dress, leisure activities and changes like the recent one which allowed women to attend soccer games), but the veterans are loyal to the organization. It seems that most of them support the hardliners, but this is not certain.

While they are not more influential in Iranian politics than the supreme leader, the latter is unlikely to make major decisions without consulting them. Whatever the constitution says, cardinal decisions relating to national security and the economy are made by the supreme leader and the Pasdaran jointly, with the senior clerics also giving input.

The parliament and its checks

Even constitutionally speaking, the Iranian parliament, the Islamic Consultative Assembly, does not count for much: it is an advisory body. Still, it is there for a reason. Debates among its 290 representatives reflect the internal debates between the hardline and reformist circles in the regime. These debates are important as a safety valve to release pressure and to demonstrate that the Islamic Republic is a democratic system. The first limit on parliament is that the Guardian Council (GC) vets the candidates who want to run for parliament. This way it can keep out undesirable personalities and manipulate, to an extent, the ratio of reformists to conservatives.

Even constitutionally speaking, the Iranian parliament does not count for much.

To maintain a democratic image, the GC has always been careful not to vet candidates too harshly. Reformists have sometimes comprised the plurality in parliament (today 41 percent of its members are reformists, and only 29 percent are conservatives). However, they never had an absolute majority because there were always many independents. Parliament has even passed legislation proposed by the reformists. However, all such legislation must receive a stamp of approval from the Guardian Council. Even when the president himself is a reformer, like former President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) or President Hassan Rouhani (in office since August 2013), if the GC does not approve the proposed legislation, it goes back to parliament.

The GC consists of 12 members, six of whom are senior clerics, while the other six have various backgrounds. They are appointed, not elected. Six are appointed by the supreme leader, and the others by the Chief Justice of Iran, who is the head of the judiciary and is himself appointed by the supreme leader.

In 1988, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini introduced an amendment to the constitution that created an arbitration institution – the Expediency Council (EC) – which is tasked with resolving disputes between parliament and the GC. The EC comprises only members of parliament, but they are all appointed by the supreme leader. Their decisions are final.

Creating the EC gave Khomeini total control over parliament’s final decisions. Currently, only six of the EC’s 47 members are reformists. Under Ayatollah Khamenei the EC is also a top advisory institution to whom he often delegates significant authority. The Expediency Council can remove parliamentary powers, investigate institutions from the Pasdaran and the Guardian Council down and, because the majority of its members have always been conservative senior clerics, they are regarded as the direct hand of the supreme leader.

Assembly of Experts

Theoretically, the Assembly of Experts (AE) is a key player in selecting the successor to Ayatollah Khamenei. It is an 88-member body of Islamic jurists, elected by direct popular vote every eight years. To qualify, candidates must be masters of Islamic jurisprudence and, like parliament candidates, be approved by the Guardian Council. According to the Iranian Constitution, the Assembly’s mandate is to appoint, monitor and dismiss the supreme leader. The next general elections for both the AE and parliament are scheduled for February 26, 2020.

Despite its nominal mandate, the council has never monitored the supreme leaders’ policies, let alone considered their dismissal. Furthermore, at least once Ayatollah Khamenei instructed the Guardian Council to dismiss a member of the AE, an order that was carried out swiftly. The AE’s dependence on the Guardian Council is so heavy that even once Mr. Khamenei departs, they will be a mere rubber stamp. Reformist politicians had advocated utilizing the AE as a check on the supreme leader’s authority, but to no avail. All such attempts have been quashed by the Guardian Council and the Expediency Council.

Still, when Ayatollah Khamenei is gone, they will appoint the new supreme leader. For now, the candidate presumed to have the support of both the AE and the GC is Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, the current head of the judiciary, an ultra-conservative who was born in the northeastern Iranian holy city of Mashhad, where the Shrine of Imam Reza is located.

Supreme National Security Council

The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) is formally the most important security and foreign policy advisory body. In reality, over the past four or five years General Soleimani had become Ayatollah Khamenei’s chief foreign security advisor.

Following Soleimani’s January 3, 2020, assassination, the supreme leader convened this body first. It is similar to, but wider than, the United States’ National Security Council. Members are top officials, like the speaker of parliament, the chief justice, the chief of the general staff, chief of the army, the commander of the IRGC, the foreign, interior and intelligence ministers and others. The responsibilities of the SNSC are defined by the constitution as: 1) determining defense and national security policies, 2) coordinating all state activities to serve the needs of defense and national security, and 3) mobilizing the country’s resources to face internal and external threats.

The members of the Revolutionary Guard are their own masters.

The SNSC is primarily an advisory body that serves the supreme leader. The final decisions are his alone. It is also the highest security coordination body. The president (today Mr. Rouhani) selects the secretary. The current secretary is Rear Admiral Ali Shamkhani. The president himself presides over the meetings. The SNSC is currently formulating nuclear policy for Mr. Khamenei’s approval and is supervising the IRGC upon his request. There is reason to believe that neither the SNSC nor the EC have really been supervising the IRGC. The members of the Revolutionary Guard are their own masters. Following the downing of the Ukrainian airplane, it is possible that some supervision will be imposed over the IRGC air force.

Who benefits?

There are fairly wide segments in Iranian society that benefit from the current political and economic system and there are others who are unhappy, with good reason. First come the clerics. Traditionally, the Shia clerics depended on the believers’ voluntary donations. Today their main salaries come from the government. In addition, they run the enormous bonyads as they see fit. The clerics’ living standard took such a quantum leap that many in Iran believe Ayatollah Khomeini’s commitment to help “the oppressed in the land” (al-mustadh’afin fi al-ardh) was meant for the clerics rather than the poor, oppressed masses.

Next is the Revolutionary Guard. As mentioned above, the IRGC controls anywhere between 10 and 50 percent of the Iranian economy. Their assets are not subject to any supervision. In addition, they own some lucrative bonyads. The benefits to the IRGC are enormous. Any change in the system will deprive them of much of what they now receive. Neither the clerics nor the IRGC and Basij have any incentive to seek economic reform. Eliminating or drastically reducing all subsidies (on food, gasoline and health services) will affect them very little. Actually, it will only make smuggling subsidized goods out of the country less profitable. They will fight tooth and nail against ending their ownership of much of the Iranian economy and other special privileges like the bonyads and ordinary corruption, even though curing the economy will require eliminating such privileges.

Iran’s crisis is not only socioeconomic, it is also generational.

The upper middle class: Entrepreneurs with large businesses and senior officials are well-connected and well off. However, the middle class and lower middle class are tightly constrained in the present system: rampant corruption and favoritism create a low glass ceiling for entrepreneurs who are not part of the deal. Still, they have more to lose in a scenario of revolutionary chaos, so their support for regime change is uncertain. Too much violence, including the destruction of banks, petrol stations and government buildings scares them. They fear a civil war like those in Yemen, Libya, Syria and Iraq. In 2019, they did not join the demonstrations in large part because, unlike the low-income classes, they could afford the rise in gasoline prices that triggered the demonstrations. The middle class will support deep change only if the ruling elite splits over reforms and the reformists guarantee an orderly process. This, however, will happen only if the regime becomes fully convinced that it will lose power if it does not enforce radical reforms.

Scenarios

Iran’s crisis is not only socioeconomic, it is generational. Most of the demonstrators in the protests 2009, 2017-18, 2019 and 2020 were young – below age 40. The Islamic revolution took place 38-40 years ago, before they were born. They are not attached to the ideology of the regime. Even though they have been taught about the ills of the previous regime, they have no personal emotional memory of it. They judge the present regime by comparing its promises with its practice, and the result is not favorable. In many of the demonstrations there were not only slogans against the clerical class but, less conspicuously, also signs of objection to religion in general.

With the regime imposing Islam in such a totalitarian manner, it is not surprising that many young people are becoming disenchanted with religion. The best example of this attitude can be found in the mass visitations to Persepolis, the ancient pre-Islamic capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great. Under the Shah, this period of history was a special focus of the regime. Nowadays, visiting the site is a symbol of protest against the regime and the religious establishment. The regime allows it grudgingly because it serves to release pressure, especially among the educated middle class. More privately, there are many young people who defy the “Islamic” state law: unmarried couples live together, women ride bicycles, and at private parties women take off the chador (full-body cloak), and so on.