The risky quest for a new nuclear deal with Iran

With the recent downing by Iran of a U.S. drone, tensions between the countries may be entering a new phase. The Trump administration has imposed more sanctions and made new threats, in hopes of getting Iran back to the table for another nuclear deal.

In a nutshell

- U.S.-Iran tensions have been escalating

- Both sides prefer to avoid a full-on conflict

- Getting back to negotiations will not be easy

The United States wants a new nuclear deal with Iran – but can it be done without a war? This is the burning issue dominating the global agenda following America’s withdrawal in May 2018 from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) signed by President Barack Obama in 2015.

Lately, this question has gained urgency, with both countries exchanging threats and appearing on the brink of war. Iran has allegedly carried out acts of terror in the region and admitted to downing a sophisticated U.S. drone near its shores on June 20. President Donald Trump, having ordered substantial retaliatory strikes on three radar and missile launching sites, canceled the operation minutes before it was due to start, recalling warplanes that were already airborne.

The president tweeted that he stopped the attack because he had been told that 150 people would be killed, adding that it was not “proportionate to shooting down an unmanned drone. … Sanctions are biting & more added last night.” He reiterated that “Iran can never have nuclear weapons.” New sanctions were indeed added a few days later, though Mr. Trump stated that they were not connected with the downing of the drone.

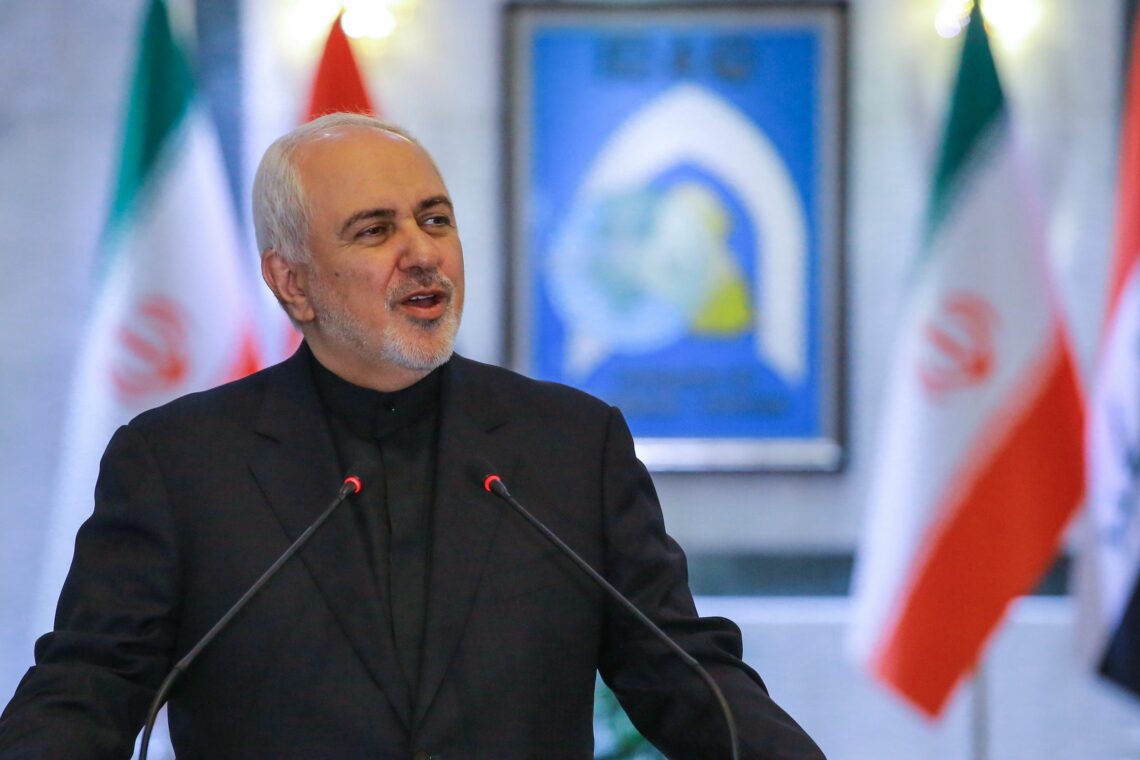

These included measures against Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader, and high-ranking members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps; a similar measure, expected to be taken against Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, was postponed so as not to impede a possible diplomatic dialogue. According to reliable sources, a massive cyberattack targeting Iranian missile and intelligence systems was carried out as an alternative to the canceled strike.

Was this an adequate response? Did the lack of a decisive retaliatory action that would have forced the enemy to halt its hostile activities weaken American deterrence? Has there been a change in the president’s position on Iran? It appears that the conflict between the two countries is entering a new phase. And it is increasingly unclear under what circumstances, if any, Washington would use force in response to Iranian provocations against American interests and those of its allies, Saudi Arabia and Israel. Could it be that after both sides demonstrated their readiness to fight, they will now move toward renewed negotiations?

No surprise

When President Trump decided to withdraw from the nuclear deal in May of last year, reinstating sanctions and adding harsher ones, he must have taken into account a possible violent reaction from Iran that could embroil America in a war.

Sanctions were intended to exert maximum pressure, explained government representatives. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo listed 12 demands the administration had placed on Iran. These included completely halting uranium enrichment and plutonium processing; making a full report on the military scope of its nuclear program available to the International Atomic Agency in Vienna; ending missile development and production; ending interventions in Iraq, Yemen and Syria and withdrawing troops from these countries; and ending support for Hezbollah, Hamas and the Islamic Jihad. It was obvious that Iran would interpret this as a declaration of war, since bowing to these demands would topple the Ayatollahs’ regime.

It is unclear under what circumstances Washington would use force against Iran.

In the past few months, more sanctions have been imposed, including the cancellation of waivers granted to eight countries to keep purchasing Iranian oil despite sanctions. On July 7, Reuters (quoting “industry sources”) reported that Iranian crude exports had dropped in June to 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) or less after Washington tightened sanctions on the country’s oil exports in May. In April 2018, exports had stood at more than 2.5 million bpd.

Sanctions on metal industries, which amount to 10 percent of Iranian exports, were also added. The economic situation was becoming so dire that Iran started making new threats, ratcheting up the tension between the two countries.

The Iranian currency has plummeted. In 2018, it took 42,000 rials to purchase a dollar; today it takes 146,000 to 160,000 rials to buy a dollar on the black market. Inflation is expected to reach 50 percent at the end of the current year, and the gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to shrink by 6 percent.

Rising tensions

In May, exactly a year after Washington withdrew from the deal, Iran deliberately ratcheted up the tension to test American resolution and persuade Europe to cling to the JCPOA. It announced that if the other signatories to the treaty (the other four permanent members of the United Nations Security Council and Germany) did nothing to ease the impact of the sanctions, Iran would start gradually violating the terms of the deal. In the same month, it reactivated centrifuges that had been idle since the 2015 agreement and started increasing its stock of 3.6-percent enriched uranium. However, it was careful not to go beyond 300 kilograms, the limit set down in that deal.

Iran also declared that starting July 7 it would enrich uranium to a higher percentage, perhaps 20 percent, significantly shortening the time it would need to reach the 90 percent required to produce a nuclear bomb. Indeed, that day, Iran confirmed that it increased the percentage of uranium enrichment to 5 percent and let it be known that the 300-kilogram threshold had been crossed. New measures would be taken every 60 days and might lead to 20-percent enrichment.

Following the first series of threats, Washington announced it had hard intelligence showing that Iran was planning attacks on American forces, and during May and June dispatched an aircraft carrier, several bombers and 2,500 troops to the region. Iran intensified its threats and then carried out several provocations.

On May 12 and June 13 six oil tankers were damaged in the Gulf of Oman, near the United Arab Emirates. Two belonged to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, one to Norway and another to Japan. The latter was hit as Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was holding talks with the Iranian supreme ruler in Tehran. On May 19, a Katyusha rocket was launched at the American embassy in Baghdad; on June 13 a drone attack on a Saudi Airport was claimed by Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Tehran has denied any involvement in these incidents. But no other country is interested in disrupting shipping in the Gulf to put pressure on the United States, or in using its proxies in Iraq and Yemen to attack American allies. A U.S. Navy vessel was able to record a video of an Iranian coast guard crew removing an unexploded limpet mine affixed to the hull of one of the tankers. Secretary of State Pompeo accused Tehran and instructed his ambassador to the UN to call for a meeting of the Security Council. Then came the downing of the American drone on June 20.

Escalation

Iran said that the drone had infringed on its territorial waters, a claim refuted by the Americans. Iran also said that it had refrained from shooting the P-8 spy plane carrying 35 airmen escorting the drone. It is unclear what actually happened. Tehran did exhibit debris retrieved from its territorial waters, but there was no indication on where the drone had fallen.

In these fraught few weeks, many thought that war was imminent, though Iranians and Americans insisted that they had no intention to go to war. Yet the feeling was that Washington had to retaliate for the downing of the drone; otherwise it would lose credibility and the element of deterrence. One is left to wonder how the decision to launch an attack and the countermanding of that decision were taken in the White House, and what each of them means.

One can assume that there were dramatic moments and significant differences of opinion. Immediately after the incident Mr. Trump tweeted that Iran made a great mistake. Following talks with his national security advisors, he slightly toned down his remarks. Then after his meeting with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Mr. Trump told the press that “someone – loose and stupid” in Iran might have made a mistake. The next day, June 21, the New York Times revealed that having ordered a strike, the president canceled it with minutes to spare. It seems that he had at first minimized the importance of the incident but was urged to act by Mike Pompeo and National Security Advisor John Bolton, both strong adversaries of Iran who undoubtedly protested at the cancelation.

Would Mr. Trump be content with a revised deal and stronger guarantees?

According to information leaked by members of the administration, Donald Trump feared that a strike would lead to a rise in the oil price, hurting America’s economy and possibly nullifying his economic successes. This was probably wrong, since the International Energy Agency was predicting that world oil consumption would fall, as the first signs of an economic slowdown began to emerge.

On the other hand, Reuters, quoting Iranian sources, reported that the president called off the strike after receiving a message from Tehran warning that it would destroy any hope of negotiations. A third possible explanation is that President Trump let himself be convinced by Tucker Carlson, an informal adviser and a Fox News commentator, who told him that unless he achieved a quick and decisive victory, he could forget about winning a second term.

Whatever the reason, canceling the operation appears consistent with President Trump’s modus operandi: proffer threats but avoid getting embroiled in a war. This is how he behaved in Syria and with the North Korean leader. It is therefore unlikely that the potential loss of human life changed his mind. Furthermore, military sources stress that when planning such an operation, an estimate of the number of potential victims is always given.

Back to the table?

In the days that followed, the U.S. president expressed his conviction that the Iranians wanted a deal. As far as he was concerned, he would accept a deal provided it was a new nuclear deal. This raises another question: what happened to the 12 conditions set down by Secretary of State Pompeo? Would the president be content with a revised nuclear deal with stronger guarantees?

There was no reason, he tweeted later, for America to be the keeper of the Gulf. The countries importing oil from the area should do their job and ensure the safety of their tankers. A later tweet was aimed at European Union countries, which instead of standing by America are cooperating with Iran and have even set up a parallel payment system, INSTEX (Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges), which will allow countries and companies to circumvent the U.S. and trade with Iran.

Yet it is their tankers which are under threat. During the G20 meeting at Osaka, the president stated that there was no hurry and that he had plenty of time. It seems as if the threat of war is off the table for now –though he insists that all options remain open.

President Trump does not want his country to get bogged down in another war in the Middle East. He has no intention of sending ground forces to the region, particularly as elections loom. But he has trouble accepting that the EU, part of the Western world, is siding with Iran, thus weakening his position. Europe is unhappy with Iran’s threats to discard important elements of the treaty. French President Emmanuel Macron sent a warning to Iran, and after Iran crossed some of the JCPOA’s red lines, dispatched diplomatic advisor Emmanuel Bonne to Tehran for talks with President Rouhani, Foreign Minister Zarif and other officials – all to no avail.

Europe still blames Mr. Trump for the crisis with Iran and is pursuing a policy of appeasement. It is turning a blind eye to Iranian-planned terrorist operations in EU countries, to its subversive activities in the Middle East, to its oft-repeated pledge to destroy Israel and to its effort to develop missiles capable of carrying nuclear bombs. Europe has let itself get caught between Washington and Tehran, which depends on it to save its economy and is now testing the limits of the nuclear agreement.

Europe blames Mr. Trump for the Iran crisis and is pursuing a policy of appeasement.

Recent incidents show both sides continuing to test each other while avoiding war. The British seizure off the coast of Gibraltar of the Grace 1, an Iranian oil tanker carrying crude to Syria in violation of European sanctions, was answered by an Iranian attempt to intercept a British tanker in the Strait of Hormuz. Faced by a British warship escorting the tanker, the three Iranians vessels turned tail.

President Trump is still trying to form a coalition of nations that would send ships to protect oil tankers through the Strait of Hormuz, showing that he continues to prefer incremental measures – avoiding war and hoping for Iran to renegotiate the agreement.

Scenarios

What might happen? Even if the American president is attempting to douse the flames, there has been no change in the core problem. Iran will not stop its subversive activities or the development of its missiles. It is still purchasing elements it needs for its nuclear program as was made clear by recently leaked intelligence reports. Europe is still looking the other way – witness the lack of official or media response in Germany to the recent alarming intelligence findings.

The Ayatollahs would like to tread softly until the 2020 U.S. elections, in the hopes that a president from the Democratic party would return to the 2015 nuclear deal. Indeed, most of the party’s candidates have pledged to do so. On the other hand, the deepening economic crisis caused by the sanctions may push Iran to attempt another violent reaction to embarrass a Trump reelection campaign. The assumption would be that he would again refrain from retaliation.

This would be a dangerous gambit. Mr. Trump could feel he had to reply forcefully so as not to be branded a coward or accused of damaging his country’s image. Iran’s announcement that its stock of 3.6 percent enriched uranium had surpassed 300 kilograms – in violation of the treaty – was a ploy to entice EU member states to intervene and find some compromise. However, it cannot afford a rift with these countries, its main supporters in the West.

One may hope that, for lack of a better option, Tehran will negotiate with America and the other signatories to the 2015 agreement. That does not mean it would comply with Mr. Pompeo’s 12 conditions, but there could be a significant breakthrough to ensure it would no longer attempt to develop nuclear weapons and long-range missiles and that it would withdraw its forces from Syria and stop threatening Saudi Arabia.

America will not settle for less. Saudi Arabia and Israel might accept the deal if it includes suitably strong guarantees. On the other hand, this is the Middle East, and a lucky strike by a rogue terrorist might set the whole region aflame. There is also one last, more optimistic possibility: that the long-suffering Iranian people finally rebel against their tyrants. But this, too, is not very likely.