Israel’s electoral conundrum

Likud, Israel’s ruling party, has been losing ground to a new coalition led by a fierce opponent of Prime Minister Netanyahu. If the next elections in March 2020 do not bring a meaningful change to the current parliamentary standoff, Israel could be facing mass demonstrations.

In a nutshell

- A caretaker government has been ruling Israel for over a year

- Parties are unwilling to make the concessions needed to form a government

- Voters could gravitate toward large parties to end the stalemate

The third round of legislative elections in Israel will take place on March 2, all efforts to form a government having failed in the April and September 2019 elections. The heads of the two leading political parties have failed to form a government. Neither Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu – who heads the ruling Likud ruling party – nor his challenger, former Chief of General Staff of the Israeli forces Benjamin “Benny” Gantz, who created the centrist Blue and White party (after the colors of the flag), were able to muster the necessary 61 votes out of 120 in the Israeli parliament.

No coalition

For more than a year, the country has been ruled by a caretaker government with severely curtailed powers. It cannot appoint senior civil servants; the police commissioner ended his term in December 2018, and the interim commissioner tasked to replace him “temporarily” is still in charge a year later. The appointments of major ambassadors to the United Nations, the United States and Egypt have been postponed. No new budget can be passed, and no new projects financed. The situation is made more complex by the many security threats Israel is facing. Though all political parties are aware of the urgent need for a stable government, they are reluctant to make the concessions necessary for a working coalition.

No single list has ever obtained the 61 seats needed to form a government alone.

This is due in part to the electoral system chosen by Israel’s founding fathers in 1949, at a time when there were only half a million registered voters: one single constituency for the whole country with proportional representation. Seats are apportioned to the lists presented by the parties according to their percentage of the vote. Parties serving particular minorities or interest groups, such as the two parties representing deeply observant Jews and the four representing Israeli Arabs, are encouraged to take their chances.

No single list has ever obtained the 61 seats needed to form a government alone. Whichever party garners the most votes must turn to smaller formations to achieve a working coalition and be prepared to pay the price. Traditionally, so-called religious parties would be the first to join a potential ruling coalition, followed by smaller right- or left-wing factions, depending on the alignment of the government being formed. So far all attempts to change this electoral system have failed.

In recent years profound societal changes have dramatically altered the overall picture. With a majority of Israelis no longer believing in a peace process (which has made little progress despite efforts by a succession of governments), the Labor Party, successor of the center-left Mapai that long dominated the political scene, barely cleared the electoral threshold.

Facts & figures

The cockpit

Led by Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu since 2009, the ruling center-right Likud Party has formed every government since that year, bolstered by the religious parties and small right-wing formations. However, its support eroded too, and in 2019 it was overtaken by the Blue and White list.

With the left in disarray and no longer able to present an alternative, voters turned to a new centrist list, Yesh Atid (“There is a Future” in Hebrew), the brainchild of journalist and TV host Yair Lapid. Formed in 2012, a year later it won 19 seats in the election for the 19th Knesset – Israel’s unicameral parliament. It became the second-largest party, leaving Prime Minister Netanyahu no choice but to include it in his coalition. Appointed minister of finance, Mr. Lapid cancelled the many subventions and privileges granted to religious parties. The parties’ angry reaction prompted Mr. Netanyahu to fire him. Since then, those parties have repeatedly stated that they will not participate in any coalition including Yesh Atid. In the 2017 election the party only got 11 seats, dropping to fourth place, and Likud continued to dominate the political scene.

The lead-up to the 2019 elections for the 21st Knesset saw a groundswell of appeals for an all-out effort to oust Likud, by then 10 years at the helm, and to get rid of its leader, now the subject of several investigations for alleged corruption. Three former generals decided to form a centrist party together along with Yesh Atid, hoping that the prestige of their military past would attract voters and ultimately let them form a stable government. Former Army Chiefs of Staff Benjamin “Benny” Gantz, Gabriel “Gabi” Ashkenazi, and Moshe “Bogie” Ya’alon, who also served as defense minister, set up a joint leadership nicknamed “the cockpit” with Yair Lapid, and with Mr. Gantz at its head.

The presence of three generals at the helm of a political formation raised quite a few eyebrows abroad and there was talk of an army putsch. However, the Israeli army is the bulwark of the country’s security, and its officers are widely admired. Many, such as Yitzhak Rabin and Ariel Sharon, went on to have political careers.

The kingmaker

The first round of the April 2019 elections saw Blue and White gain an impressive 35 seats. Likud also won 35 seats and, with the support of the religious parties and of two small right-wing parties, reached 60 Knesset members – one short of the required majority. With five seats, Yisrael Beitenu (Israel Our Home), a right-wing party mainly supported by Russian-speaking Israelis from the former Soviet Union, was expected to join the Likud-led coalition.

The lead-up to the 2019 elections saw a groundswell of appeals for an all-out effort to oust Likud.

However, founder and chairman Avigdor Liberman announced that he would only join a liberal, national unity government with both Likud and Blue and White. The request was a nonstarter since Mr. Gantz had emphatically stated that he would not be part of a coalition led by Prime Minister Netanyahu should the latter be indicted.

Blue and White could not try to woo the 16 members of religious parties because of their opposition to Yesh Atid leader Yair Lapid. Furthermore, it could not form a government with its own 35 Knesset members and the 10 remaining members of the once impressive Israeli Left – which built the institutions of the country even before its independence. The Arab lists, keen to get rid of a prime minister known for his rhetoric against Arab voters, were thought to tacitly support the Blue and White coalition, but they received only 10 seats.

Reshuffling and indictment

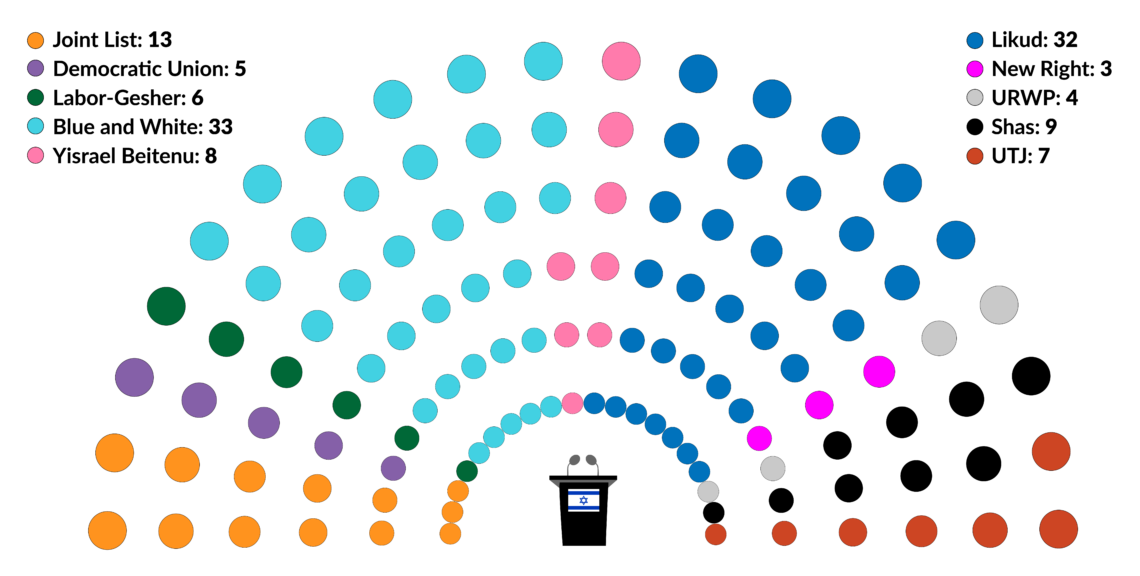

New elections were called, and Israel went to the polls again in September, with fairly similar results. Blue and White lost two seats, but its 33 were better than the 32 won by Likud. The latter lost three seats and came in second for the first time in 10 years. Still, Prime Minister Netanyahu could count on the support of his usual allies for a total of 55 Knesset members, while former Chief of Staff Gantz could only muster 44, his left-wing allies having won an extra seat.

Yisrael Beitenu, which had gone from five to eight seats, was once again the kingmaker. Tasked by President Reuven Rivlin to try and form a government, Prime Minister Netanyahu was unable to persuade Yisrael Beitenu leader Avigdor Liberman to renounce his vow to only join a liberal national unity government and team up with Likud. Blue and White also tried to sway Mr. Liberman, to no avail.

President Rivlin suggested a way out: a unity government with one leader becoming prime minister for a set period and then being replaced by the other. Prime Minister Netanyahu, backed by a greater number of Knesset members, would be the first, but he would also leave his post when an indictment would make it necessary for him to focus on his legal issues. Thus, Blue and White leader Benny Gantz could reassure his voters that he would not share power with a man under indictment. Half-hearted negotiations on this potential arrangement dragged on, hampered by deep-seated mutual distrust.

On November 11, the state prosecutor indicted Prime Minister Netanyahu on charges of fraud, bribery and breach of trust, making it difficult for Blue and White to keep negotiating.

Meanwhile, there was no real incentive for Prime Minister Netanyahu to step down. With a third round of elections, he would be able to remain in place until a new government is formed, which would allow him to try to obtain parliamentary immunity against indictment. In any case, the law allows an accused minister to remain in office until he has been convicted and the judgment is final.

Yet constructive solutions could have been found. Once again, petty considerations and egos torpedoed the most promising leads. Both sides used vitriolic rhetoric. Prime Minister Netanyahu and his family were attacked daily, though surveys show his popularity is still high. For his part, he accused former Chief of Staff Gantz of colluding with terrorists, since Blue and White had toyed with the idea of a minority government supported by the four Arab formations. In the latest election round, the Arab parties had wisely formed a unified list and gained three seats, reaching 13 members and becoming the third party in the Knesset. But still, combined with Blue and White’s 44 seats, the two groups together would only have 57.

The New York Times stated that ‘the legal case against Prime Minister Netanyahu is not clear cut’.

Prime Minister Netanyahu and his supporters accuse the police and prosecutors of trying to remove him from power through legal means. They maintain that the left, after repeatedly failing to win the elections in the past decade, is deliberately targeting the prime minister through relentless leaks from secret deliberations and testimonies that should not have been made public. It should be noted that in a November 22 editorial, the New York Times stated that “the legal case against [Prime Minister Netanyahu] is not clear cut.”

Nevertheless, there was a growing awareness that his departure could be beneficial. Gideon Saar, member of the Knesset, former education minister and interior minister, currently sidelined because of his opposition to Prime Minister Netanyahu, announced that he was ready to challenge him and demanded that primaries be held for the leadership of the party. The prime minister accepted after some hesitation. Elections took place on December 26 after a short and bitter campaign. Both contenders toured the country and held rallies to drum up support. Prime Minister Netanyahu received 72.5 percent of the vote. The landslide victory was a much-needed boost for the embattled Likud leader. Mr. Saar acknowledged his defeat and pledged to do all he could to help Likud win the forthcoming elections.

Scenarios

Israel is once again caught in electoral fever, with a caretaker government and urgent decisions on hold. The wait will be mercifully short, but the campaign is expected to be ugly. The conundrum has not been solved. Current surveys show no significant changes as yet, but they have been wrong in the past.

There are signs that voters on the left and on the right may decide to desert smaller parties to reinforce the two main formations and end the stalemate. Such a development might work in favor of Likud, which is making an all-out effort to reach 61 seats without Yisrael Beitenu.

As things stand, Blue and White does not appear likely to reach that number, even if Mr. Liberman were to join the coalition. Conversely, if he decides to join a Likud coalition, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s path to a new term would be smooth.

Should further uncertainty arise, and with the specter of a fourth election looming, there could be public unrest and mass demonstrations. Will it be enough to make voters and politicians alike think twice? Lastly, the Middle East being as unstable as it is, a serious flare-up at the borders could convince the two blocks that a compromise has to be found immediately for the good of the country, and a national unity government could be formed.