Italy’s Covid crisis plan: More government intervention

The Italian government wants to use the Covid-19 crisis to lead the country back on the path to economic recovery. Its plan has been to use EU funds to boost spending – but increasing state intervention discourages foreign investment and crowds out private businesses in Italy.

In a nutshell

- Italy is tackling economic difficulties with state intervention in private companies

- The country wants to use EU rescue funds to direct the economy

- History has shown such moves tend to end badly

Governments tend to grow when a crisis hits. In Italy during the Covid-19 pandemic, that adage proved true again. How much government involvement increased, however, has surprised even those who are used to Italy’s penchant for administrative overreach.

The country’s economic problems predate Covid-19, and Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte’s administration claims it will take advantage of the pandemic to tackle them. There is little in the government’s strategy to raise the spirits of the private sector. In the halls of power, the mindset is that growth and “sustainability” – the ruling parties’ favorite catchword – are only possible under robust state leadership.

Is state intervention the answer?

Over the past few months, the Conte administration has engaged in a flurry of economic activity. Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP), an Italian bank that acts as a financial arm of the government, is now the biggest investor in Borsa Italiana, the Italian stock exchange. It owns a direct or indirect stake in some 500 listed businesses. The bank is not usually an active investor that would steer companies in a particular direction. Still, CDP’s very presence in companies’ capital structure makes them less contestable and ties them to the government.

In October 2020, CDP became a shareholder of Euronext, which acquired Borsa Italiana from the London Stock Exchange. It is also pondering how to acquire an 88 percent stake in Italian highway builder and operator Autostrade, currently owned by Atlantia. The latter is an infrastructure sector group whose main shareholders are the Benetton family. The Italian government and much of the public consider Atlantia responsible for the collapse of the Morandi bridge in Genoa in 2018. CDP is deciding between buying Autostrade, or Atlantia as a whole, to oust the Benetton family from the Italian highways.

Italy’s economic problems predate Covid-19 – and there is little in the government’s strategy to raise the spirits.

CDP is also a shareholder of Telecom Italia (TIM), Italy’s former telephone incumbent, and owns 50 percent of Open Fiber, its competitor in developing an ultra-broadband network. A merger of the two broadband networks is being worked out. State-owned investment agency Invitalia has reached a deal to take over a controlling stake in Ilva, a steel producer that every Italian government has eyed since 2012, when an investigation into breaches of environmental regulations forced out the old majority shareholders, the Riva family. Ilva, whose Taranto plant has some 8,000 workers in a region hit hard by unemployment, was too big to fail. Before Prime Minister Conte came to office, however, the plan was to sell the firm to a capable steelmaker. Italian taxpayers are now set to pour some 1.1 billion euros into the company by 2021.

Both the Autostrade and Ilva stories have further damaged Italy’s already shaky reputation when it comes to attracting foreign investment. At Autostrade, the government rushed into nationalization, trying to push the Benetton family out as quickly as possible. Since it was unable to do so, it has ended up in a complex bargaining process that may finally end this year. At Ilva, ArcelorMittal was promised immunity against the company’s past environmental transactions in return for taking it over. But the Italian Parliament later canceled the immunity, prompting ArcelorMittal to back out of the original deal. None of this sends a message that foreign investors will be welcomed.

EU funds

The Conte government’s pandemic strategy consisted of calling for European aid, in the form of rescue funding. To access money from the NextGenerationEU program, member states are required to produce a National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

Facts & figures

The government aims to increase Italian state intervention by raising public investment to at least 3 percent of GDP (it averaged 2.2 between 2017 and 2019). It also wants to bring spending on research and development above the EU average, which was 2.2 percent of GDP in 2018, compared with 1.4 in Italy. Moreover, it plans to double the Italian economy’s average growth rate and increase the employment rate by 10 percentage points.

Six point plan

How will it accomplish all this? The plan puts forth six “missions” for allocating resources:

- €74 billion for “ecological transition”

- €49 billion for “digitization”

- €28 billion for “sustainable mobility”

- €19 billion for “education and research”

- €17 billion for “gender equality and social and territorial cohesion”

- €9 billion for health, especially proximity assistance and telemedicine

By 2023, all projects must be approved and 70 percent of the grant money spent. The rest must be spent by 2026. Since decisions on how to distribute the Brussels largesse must be made quickly, Prime Minister Conte has proposed a hierarchical governance scheme. A “czar” will lead each mission. Political oversight will come from a committee comprised of the prime minister, the economy minister and the economic development minister. The European affairs minister will be the point of contact between the European Union and the government.

Former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has cried foul and threatened to take his small party, Viva Italia, out of the coalition government, depriving it of its majority. The suspicion is that all that money will land in the hands of the prime minister’s friends and political allies. In any case, the only project that has been proposed so far is the construction of a high-speed rail line along the Adriatic Riviera.

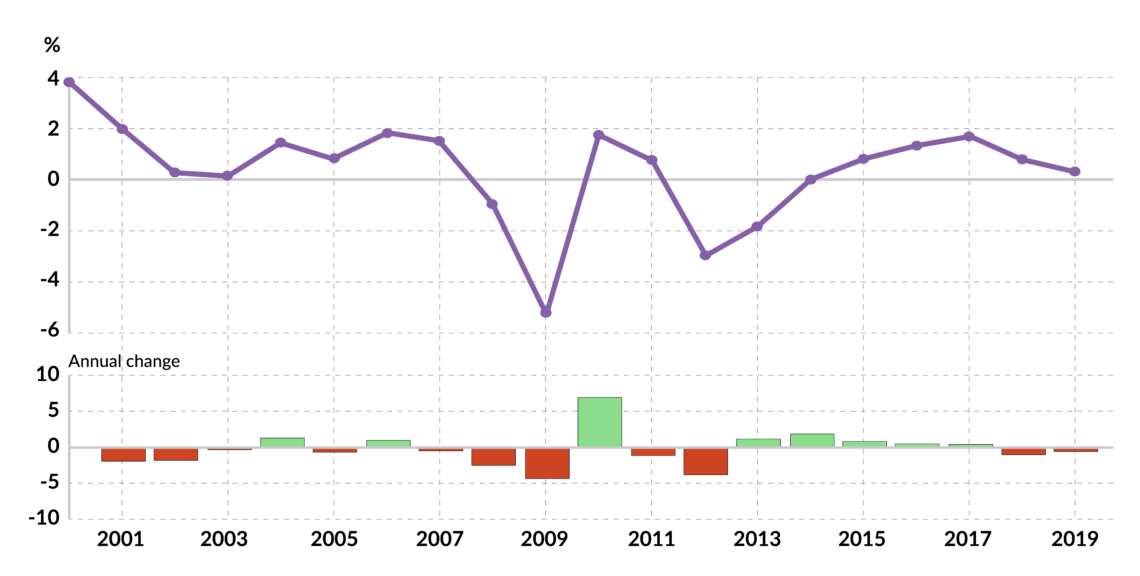

One of the biggest unknowns is how private-sector involvement will work. The pandemic hit Italian companies hard. While the mid-year recovery was strong, the new lockdowns in the fall and winter months slowed that momentum. In 2020, Italy’s economy likely shrank by 10 percent. The companies that survive would probably welcome new projects, but complex bureaucracy and overbearing government involvement could dampen any positive effects.

Private-sector outlook

The government took on 194 billion euros of debt in 2020 because it needed to make up for the shortfall in taxes that firms were unable to pay, and to compensate for the lack of private business activity. It is difficult to imagine what shape the country will be in once the pandemic subsides. Small and medium-sized businesses are a crucial part of Italy’s economy. The private sector filled the gaps that public firms did not, and provided goods and services to big state companies.

Broadly speaking, Italy is divided between a few very efficient, export-driven companies (mostly manufacturers), that compete in the global market, and a large number of companies servicing the Italian market and that typically use government protection to keep out competition. Over the last decade and a half, the first group of companies grew stronger. In 2018, exports were 15 percent higher than in 2007, signaling that the companies active in open markets had adapted successfully.

Italy’s pool of entrepreneurial talent is strong, but little is being done to build on it.

Can those firms repeat that success? Italy’s pool of entrepreneurial talent is strong, but little is being done to build on it. Italian state intervention in the form of government investment tends to crowd out private investment. And the more the state fights to control assets, the more precarious private shareholders may feel.

It is telling that both the government and the opposition parties agreed to a six-month extension of the so-called “golden share” provisions that prevent Italian companies from being taken over by foreign businesses. Beyond the nationalist propaganda, Italian entrepreneurs’ property rights are curtailed, as they cannot sell their assets to whom they see fit. The Conte government extended the application of this rule and there is no political will to return to the previous state of affairs.

Scenarios

Throughout history, Italy’s economic development has come at unexpected moments and from unexpected places. When the government was preoccupied with supporting heavy industry, Italy’s small, private, consumer-oriented companies were blossoming. But those were different times. Now that resources are much more mobile, the move towards Italian state intervention is essentially saying it is not interested in attracting foreign capital.

Could Italian business make another spectacular comeback? It is a possible scenario, though others are likelier. More and more firms may seek to partner with the government, creating a perception of unfairness among those that cannot do so. In steering the economy in the direction it chooses, the government will leave some businesses behind. In a country where regulations and taxes are suffocating, many entrepreneurs will choose to move away or close up shop.

Another possibility is that government funds will create dependence. Italy’s economy will increasingly trend toward favoring government-controlled businesses. The idea that the state will force down a company’s stock price if it plans major layoffs will not encourage better business. On top of that, companies will devote their resources to obtaining EU rescue funds, rather than investing in innovative projects or making their operations more efficient. The Italian government is on track to become an even bigger investor in the country’s firms. And when it is not a shareholder, it will be a major provider of support.

Italian state intervention is not a new experiment: It has ended in financial crisis before. Now, the government believes public finances can be more generous than ever while it piles up unlimited debt. That belief will eventually be put to the test.