The Italian challenge

Italy’s public finance troubles are making waves again, but the new budget proposal does not spell disaster, nor should debt servicing create a big problem, considering today’s low-interest rates. But Italy’s leaders have decided to transform their conflict with the EU into a casus belli. Will it end in an Italian crisis or a new EU architecture?

In a nutshell

- Italy’s financial problems are less dramatic than they seem

- The real problem is that EU policies have encouraged member states’ profligacy

- Rome’s fight with Brussels challenges the EU’s ability to continue such policies

Italy’s new government continues to send ripples throughout the European Union and financial markets. At first blush, it is doing nothing dramatic. According to the government’s initial announcements, in 2019 the budget deficit should reach 2.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), as opposed to 1.6 percent (the previous figure accepted by Brussels) and to 2.0 percent (the expected figure). Although the revised level is higher than one would want, it is no foretaste of financial disaster, even considering Italy’s high public debt (133 percent of GDP) and its low growth rate (1.2 percent in 2018). Yet, market players have been taken by surprise and the EU authorities have issued biting criticism.

The Italian government has been taken aback. The leaders of the government coalition have reacted by telling their electorate that Italy is under attack by international speculators and the wicked EU commissioners. Promises to reduce the deficit to 2.1 percent and 1.8 percent of GDP in 2020 and 2021, respectively, have not changed the overall perception. Is Italy on the verge of bankruptcy, or will Rome show up with something at the eleventh hour?

To identify the key variables that will shape developments, it might be useful to look beyond simple accountancy. After all, figures about public indebtedness are worrying only when creditors start believing that debtors might not pay them back. No EU economy is currently in such a situation, because today all countries can refinance their long-term debts at fire-sale prices. Of course, normality is not the real negative rate of interest paid by the German government on its public debt. The same applies to the Italian or Greek rates, which stand at less than 2 percent in real terms.

Much of the noise about Italy’s budget law has little to do with the financial features of the Italian debtor.

This explains why, for example, Italy still needs “only” 3.6 percent of its GDP to service its public debt. Markets will start worrying only when a highly indebted country’s long-term real interest rate reaches 4 percent. This is not yet the case for any EU member.

That is not to say that there is no Italian problem. Rather, much of today’s noise about Italy’s opaque budget law probably has little to do with the perceived financial features of the Italian debtor.

Lack of legitimacy

Let us focus on another source of concern to which the Italian challenge draws attention, and to which the Italian economy is vulnerable. The EU has seemingly learned very little from the 2008 financial crash and the Greek crisis and is still unable to withstand imbalances. Following the 1992 Single European Act, the EU has been widening its scope and ambitions. It has engaged in efforts to centralize more and more decision-making power to bring about social justice and “fairness” throughout the continent.

Yet, massive redistribution requires large sums of money. The EU would have needed free access to the euro printing machines and/or to European taxpayers’ pockets. In recent years, the printing machine has been operating allegedly to come to the rescue of European savers – in fact, of European troubled banks – but taxpayers (and national governments) have remained far from excited at the idea of financing centralized fiscal policies.

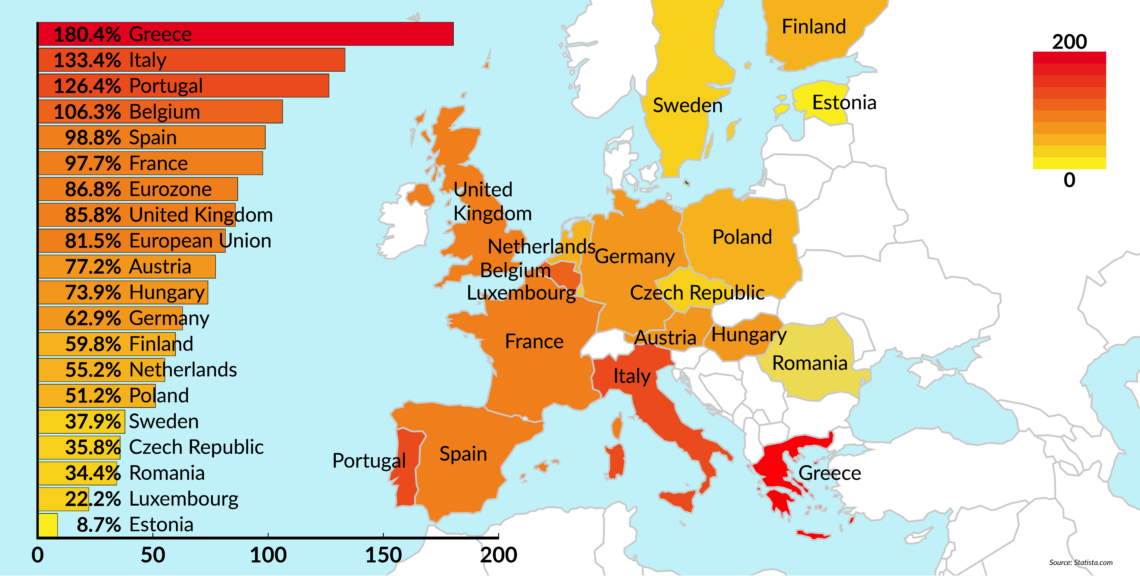

Facts & figures

Not just Italy

National debt-to-GDP ratios, selected EU countries, Q1, 2018

Moreover, as the EU mission becomes less and less evident, the lack of its institutions’ social legitimacy becomes clearer: social justice on a continental scale is perceived as a threat. The call for a European identity falls on deaf ears, and the informal, unfriendly tones with which some commissioners address the political leaders of selected member governments end up encouraging populist rhetoric and a misplaced feeling of national pride. The result is that the advocates of irresponsible economic policymaking have found increasingly receptive audiences, while the EU authorities have failed to react and provide satisfactory responses.

‘Do nothing’

Given this broad framework, three scenarios could unfold soon. One includes the possibility that nothing happens: the European Union would not abandon its ambition to promote an extended welfare state, centralize regulation and influence fiscal policy in member countries. But it would also fail to acquire new powers to tax and spend. This “do-nothing” recipe certainly requires minimum effort, but can work only if all countries have healthy economies and if their governments can continue to rely on Brussels’ technocrats to marginalize local parliamentary opposition. This scenario is somewhat likely.

Of course, this is all right if the European Commission and the governments of the member countries pursue similar agendas. When this happens – and it has been happening for the past 20 years – the Commission reciprocates the favor by relaxing its standards for monitoring public finance.

The difference between trouble and disaster will depend on the quality of the leaders in Rome and Brussels.

If the economic picture becomes bleaker, however, the outcome is trouble, possibly disaster. In this light, the main challenge set by Italy lies in having questioned the implicit contract between the national governments and the Commission. The difference between trouble and disaster will depend on the quality of the leaders in Rome and Brussels, and on their ability to back off without losing (too much) face.

EU: pull back or push forward?

A second scenario regards the possibility that the EU stops acting as a watchdog. This most likely scenario does not require Brussels to give up its regulatory functions, but it would require emphatic declarations that in the future, no EU institutions will ever bail out governments or companies in the member countries. That would also apply to the European Central Bank, which would be prevented from acting as a lender of last resort. If this happened, the Italian leaders would deserve credit for having forced the EU to revise its role, and the current Italian challenge would probably be defused.

On the one hand, Italy’s leaders could no longer blame the EU for threatening the country with allegedly insane budgetary constraints and, on the other, Italians would have a clearer idea about the causal relationship between the value of their financial wealth and their government’s reputation. The incumbent coalitions would be forced to change tack or risk being kicked out of office.

The Italian challenge is indeed a source of anxiety, but it might provide a healthy shock.

A third scenario would emerge if the Commission tried to take advantage of the challenge and enlarge its powers by proposing to provide wider and more credible safety nets in exchange for greater decision-making power over fiscal policies. Ironically, in this scenario, the interests of the EU bureaucracy and of the rising populist movements in Europe would come ominously close. European populist electorates would be happy to see an expanded role for a better Europe, where “better Europe” would mean that populist leaders dictate the agenda, while the bureaucrats implement the rulings and possibly expand their discretionary powers. For the near future, this scenario is unlikely.

New leaders needed

Today’s Italian troubles – a mix of political incompetence and populist profligacy – is less a signal of the country’s fundamental weakness than of the disorder created by a class of arrogant EU leaders who have created misplaced expectations while becoming a scapegoat for discontent and a catalyst for adventurous local politicians.

Certainly, Italy is guilty of having produced a botched budget law and proposed imaginative figures about its future growth. Brussels and Frankfurt, however, have little reason to pontificate. After all, by protecting Italians from market pressures and warnings, they have allowed them to reach the edge of the cliff.

Italians are finally waking up. Hopefully, they can avoid the worst. Yet different, unpretentious and market-friendly EU institutions would have given Europe a much smoother ride. New solutions are badly needed. But perhaps the populists are correct: new solutions require new leaders. The Italian challenge is indeed a source of anxiety, but it might provide a healthy shock.