Will Italy make it?

Italy’s public finance situation is worrying global markets, just as the newly-elected coalition that made promises to voters that could blow past deficit targets and push Italy toward default, bailout, or an exit from the euro. But the Five Star Movement and the League are more likely to moderate their economic programs.

In a nutshell

- Italy’s public finance situation is worrying, but not yet disastrous

- The new populist coalition made costly election promises that could bring about default or a euro exit

- To avoid a crisis, they must spend enough to appease voters but not enough to spell disaster

- If tension between the two populist parties grows, the government could collapse

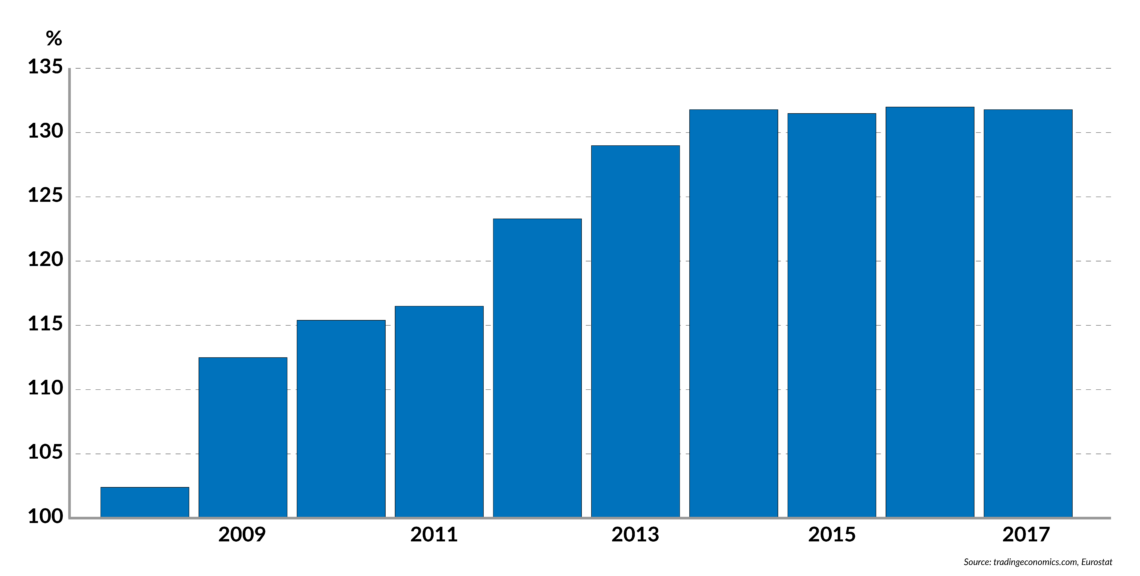

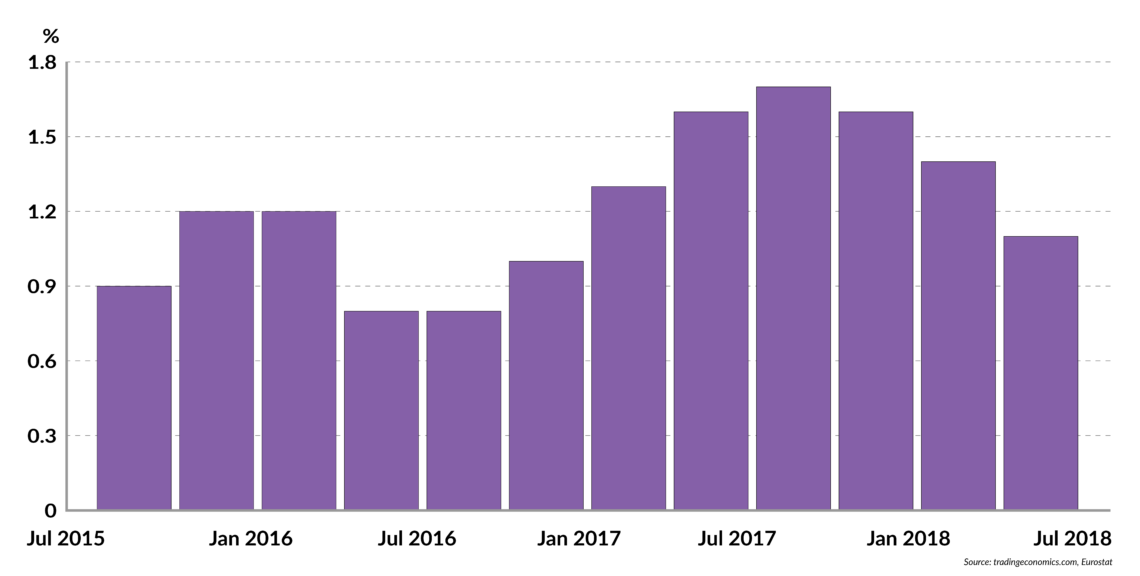

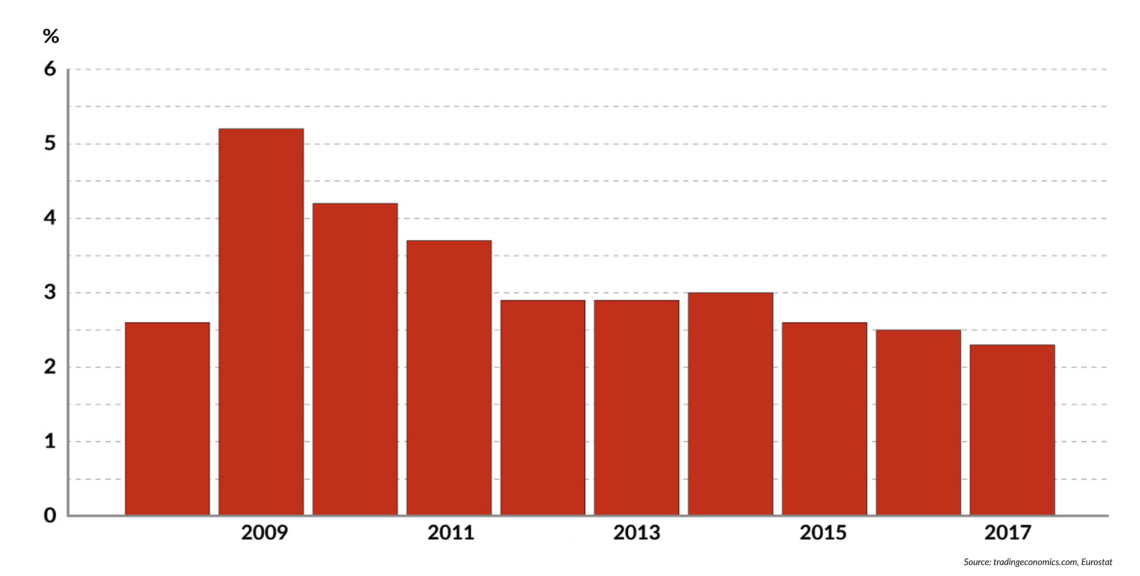

The hazardous condition of the Italian public finance situation is well-known. Its public debt amounts to some 132 percent of gross domestic product, its budget deficit could easily reach 3 percent of GDP by the end of this year, and its economy is growing at an annual rate of about 1.2 percent. In short, high public indebtedness makes Italy vulnerable to rising rates of interest, while slow economic growth makes it difficult to reduce the debt burden relative to GDP.

All of this has the international financial community worried, as witnessed by the spread on the 10-year Italian treasury, which jumped from 120 basis points in May 2018 to over 300 points in mid-August. If Italy failed to take advantage of the European Central Bank’s friendly attitude – extremely low interest rates and significant purchases of Italian treasuries – what happens once the eurozone monetary authorities revert to a less generous stance? And what will Brussels do if the Italian public finance picture deteriorates further?

In truth, the Italian context is worrisome but not desperate. The budget deficit is currently modest, and if policymakers were able to freeze public expenditure in real terms and make the economy a little more business-friendly, the rate of growth could double and gradually reduce the relative weight of the debt. Of course, improvement could come even faster if public expenditure were frozen in nominal terms or cut. But most observers fear that will not happen, and that in fact, the current populist government will move in the opposite direction.

Politics or programs?

Certainly, if the government followed the economic programs of the two ruling parties – the Five Star Movement and the League – disaster would be inevitable. Between the League’s proposal for a 15 percent flat tax on personal income and the reduction of indirect taxation, and the universal guaranteed income (on top of the existing welfare state provisions) promised by Five Star, the budget deficit would rise to nearly 8 percent of GDP. That figure would soar to 10 percent if the predictable increase in debt-servicing costs is considered.

Facts & figures

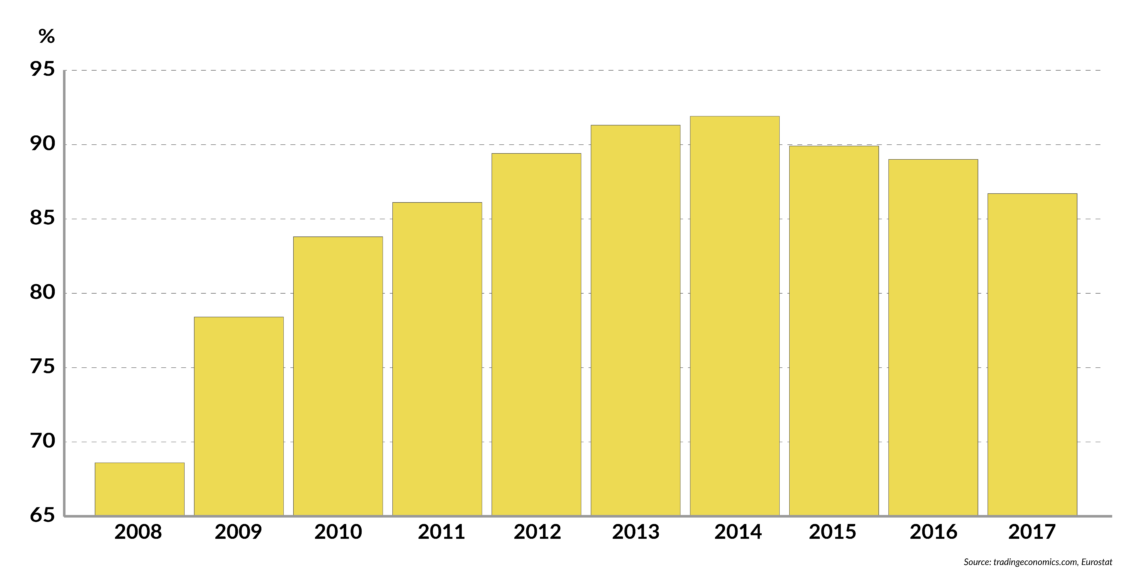

Italy, annual GDP growth rate (%)

Any mitigating consequences predicted by the celebrated Laffer curve would not significantly change the picture. Understandably, explanations by populist leaders that the deficit would be financed by quitting the euro and printing new lire are not very reassuring.

Until late July, markets did not worry too much, possibly because operators trusted that these economic programs were empty promises designed to attract voters. The situation deteriorated when it became clear that although those electoral promises were indeed nearly empty, what remained was still plenty worrying enough, even if they were not as catastrophic as it had seemed.

Put differently, even though the probability of Italy leaving the eurozone has receded, the reckless politicians who endorsed such an idea remain in power and are capable of inflicting considerable damage. It has become clear that these leaders are inclined to follow the mood of the moment and blame “unregulated capitalism” for all sorts of problems. Although they do not have the spine to make catastrophic moves, they are incompetent enough to create uncertainty and scare away investors.

In this context, three scenarios may follow. Their likelihood will be defined in September, with each generating a different outlook for public finances. One scenario is that the incumbent coalition parties insist on meeting their voters’ expectations of a flat tax and universal income. In the second, Italians would see a watered-down version of those two promises. The third scenario would emerge if the two parties ended up fighting about what to do and the coalition broke apart.

Scenario 1: Promises kept

As mentioned, the introduction of a 15 percent flat tax and of a universal basic income would be very expensive. Moreover, it would be difficult to introduce one and shelve the other. If only the flat tax was enacted, Five Star voters would not understand why the government would favor the “rich” in the North and forget about the poor in the South, where the party gets most of its votes. Conversely, those who voted for the League (mainly in the North) would revolt if they were forced to transfer additional resources to the South with no compensation in the form of lower taxes.

Can the coalition meet both of these targets while keeping the budget deficit within reasonable limits? To do so, they would have to cut spending by at least 100 billion euros — a political impossibility. When Finance Minister Giovanni Tria suggested eliminating a bonus that the Renzi government had handed out to low-income households (worth around 10 billion euros annually), the leaders of the current coalition mocked him and dumped the proposal. Trimming the bureaucracy and other expenditures (be it pensions, education or health) would be suicidal for any populist party, and the current yellow-green coalition is no exception. In fact, a few days ago, current minister and League member Giulia Bongiorno made known that Italy needs to hire 450,000 new civil servants.

Facts & figures

Italy, government budget deficits (% GDP)

In other words, if the promises are kept, some kind of Greek-style default on the country’s public debt will follow. Depending on how the government would react to such a default, three things could follow. One would involve a rescue plan organized by the European Union, conditional on Italy’s compliance with strict budgetary rules imposed from Brussels and Frankfurt. Alternatively, Italy could simply default without leaving the euro: those who hold Italian treasuries in their portfolios would suffer badly, and the Italian government would find it virtually impossible to run budget deficits for quite some time. A third solution would require that Italy leave the euro, introduce capital controls, and resort to the printing press to finance its profligacy; in other words, Maduro without oil or Erdogan without Allah.

Scenario 2: Modest spending

The second scenario is more realistic and closer to the Italian political tradition. Simply put, the government could choose to do nothing to reduce the current budget deficit and increase public expenditures for the benefit of low-income pensioners and the unemployed. But such an increase would be relatively modest – enough to blame the EU (and possibly Mr. Tria) for not being able to spend more, but not so much as to bring major financial troubles. The Italian public debt would probably stop making headlines, and the yield spread would come down to about 220 points, at least until next spring.

One scenario would see a modest spending increase, enough to blame the EU but not so much as to bring a crisis.

To work out, this scenario requires that a few things happen. The government coalition must remain cohesive. Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte has to make a clear statement that the budget deficit will not exceed 2 percent of GDP, and he must not get slammed by the coalition’s leaders. Finally, global interest rates must not shoot up (which they won’t).

Scenario 3: Confrontation

A third scenario would materialize if the coalition breaks apart before the end of the year. Most likely, Five Star leader Luigi Di Maio and League leader Matteo Salvini are not planning to pick a fight before the next European elections, scheduled for May 2019. But the incompetence of the two leaders (and their closest advisors) might cause unintended tensions, and the situation could get out of control. Much depends on whether Mr. Di Maio and Mr. Salvini understand that they cannot both rock the boat and stay in power, and on whether they are able to discipline the rank and file of their parties.

Mr. Salvini does seem in control, and he is probably well aware that his electorate will be happy as long as he does not raise taxes and create trouble with the EU. Five Star’s Luigi Di Maio is more fragile. Should his position weaken, Mr. Salvini will have to distance himself quickly from unpopular policies and ask President Sergio Mattarella to call for new elections. Then he would have to win and put together a new government with the moderate parties, which at the moment number two.

Facts & figures

Eurozone area government debt (% GDP)

Both are in deep trouble; Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia is weak and would barely garner 10 percent of the votes, while Matteo Renzi’s Partito Democratico is an empty vessel that commands about 15 percent of the electorate. Mr. Salvini could strike a deal with the remnants of Forza Italia, or perhaps absorb it, and avoid bargaining. But all told, this ploy is much easier to describe than to execute.

In the meantime, anything can happen to the Italian debt. Based on past experience, the informed guess is that nothing will happen. Yet a political crisis could also bring instability, increases in spending, a decrease in revenue and mounting regulation. In such a situation, the implosion of the Five Star Movement would no longer be good news, but the beginning of very serious trouble.