A rising Ivory Coast faces an eventful 2020

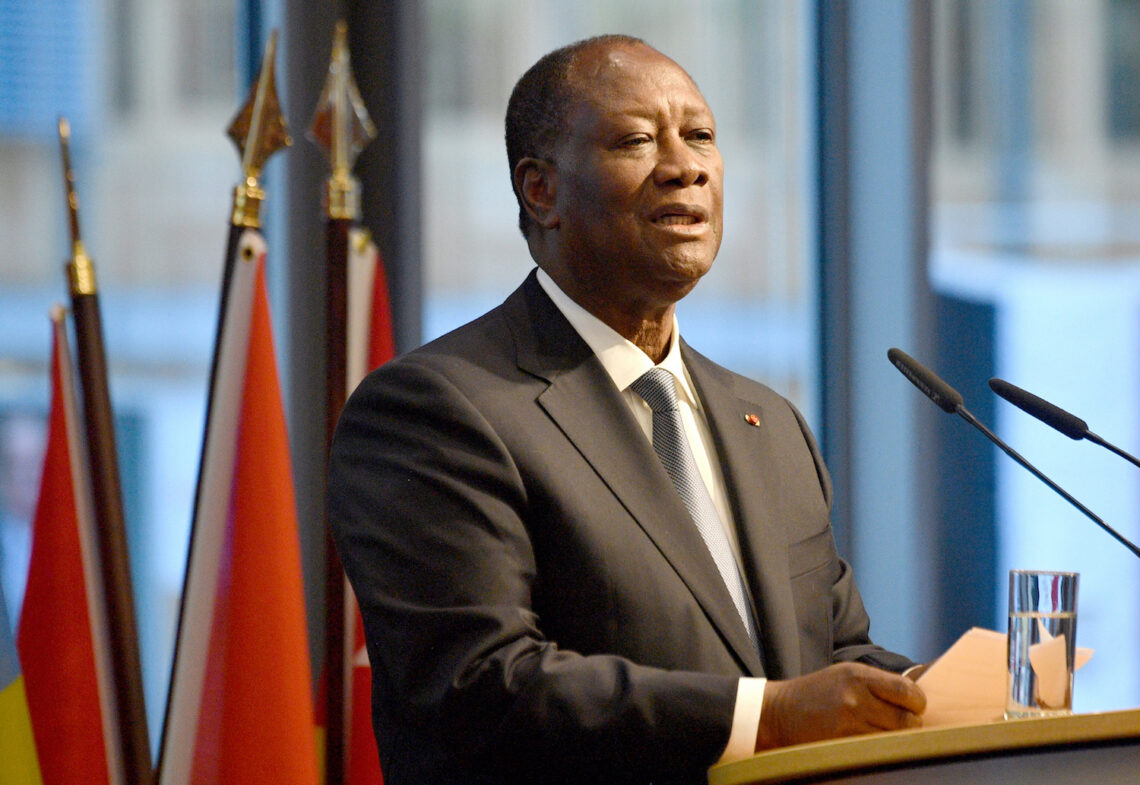

After years of instability, Ivory Coast has become a regional rising economic star. However, presidential elections in 2020, together with rising social discontent, may keep President of Ivory Coast Alassane Ouattara away from remaining in power. He will have to balance various considerations to maintain the country’s stable trajectory.

In a nutshell

- After years of civil war, Ivory Coast has become a regional star

- President Ouattara faces new political challengers

- Inequality and polarization could jeopardize recent progress

- The outcome of next year’s presidential elections will be critical

In less than two decades, Ivory Coast has experienced two civil wars (2002-2007 and 2011), an eventful power transition (2011) and, at long last, eight years of increasing political stabilization and robust growth (2011-2019). The country, which was immersed in a conflict involving rebel militias in 2011, has now become an example of Africa’s economic potential and a regional powerhouse.

However, as the 2020 presidential elections approach, that recent progress is being put to the test. It becomes clear that despite the achievements, old political dynamics and rivalries have persisted and will likely become determinant over the coming year.

Success drivers

After a “lost decade” (2000-2010) during which growth averaged 0.9 percent and the total investment rate fell below 10 percent of the GDP, Ivory Coast has, since 2011, experienced an average growth rate of 8 percent (among the fastest in the world) and is now the largest economy in the West African Economic and Monetary Union. It is an impressive achievement — especially considering that, unlike some other fast-growing countries on the continent, Ivory Coast’s economy has not intensively exploited natural resources to drive growth.

Growth has been driven by public investment; by increasing exports earnings from traditional products like cocoa, rubber or palm oil and from natural oil and gas; productivity increases in the relatively diversified and expanding manufacturing sector; and private sector engagement and expansion in the telecommunications, agribusiness and construction sectors, which have attracted increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) flows. To be sure, the economy remains vulnerable to external shocks. Ivory Coast is the world’s leading cocoa producer and exporter, accounting for 40 percent of the global supply, and a fifth of the country’s 25 million population is estimated to depend on cocoa for their livelihoods. But the overall trends suggest that the economy will become increasingly resilient.

The investment and business climates have dramatically improved after a series of reforms.

The main factor in this remarkable economic performance has been efficiency. President Alassane Ouattara, who had previously served in the International Monetary Fund and the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), made fixing the economy his first priority after coming to power in 2011. His National Development Plans (2012-2015), (2016-2020) have been taken seriously, and the country’s installed electrical generation capacity has increased by 56 percent. The investment and business climates have dramatically improved after a series of reforms; between 2011 and 2019, the country rose 46 positions in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business ranking.

Another crucial element of Ivory Coast’s achievements has been the legitimacy enjoyed by Mr. Ouattara, allowing the president to focus on the economic front and implement a developmental and reformist plan without making significant concessions. This legitimacy, both internal and external, derived from a combination of factors. During the 2010 presidential elections, Mr. Ouattara won 54 percent of the vote against the incumbent Laurent Gbagbo’s 46 percent. Then, Mr. Gbagbo refused to abandon power and resorted to a campaign of violence. The winning political coalition, known as the Rally of Houphouetists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP), united the conservative Democratic Party of Cote d’Ivoire (PDCI) and Mr. Ouattara’s liberal Rally of the Republicans (RDR). The government’s legitimacy was reinforced in the 2015 elections when President Ouattara — now running as the RHDP candidate — was reelected with 83.7 percent of the vote.

Factors of destabilization

However, the pillars of Ivory Coast’s stabilization are now at risk. The PDCI has left the RHDP coalition, as party leader and former president Henry Konan Bedie has announced his intention to run for the presidency in 2020. Meanwhile, former president Laurent Gbagbo – who had been accused of war crimes by the International Criminal Court (ICC) – was acquitted, and has expressed the wish to return to Ivory Coast ahead of the presidential elections.

This environment of political fragmentation and polarization will likely be exacerbated by rising social discontent, as the country faces a critical socioeconomic juncture. Poverty has declined and the quality of and access to services like health and education has expanded. However, the poverty rate remains high, at 46.4 percent (in 2011, it was estimated at 51 percent). Moreover, perceptions of inequality have become more politically charged, especially in urban centers. Even if absolute poverty has decreased, the politics of inequality may drive further popular contestation and weigh on the current trajectory of stabilization and growth.

More disturbing, it has become evident that old habits persist under a fragile peace and the slow reform of the security sector. The militarization of politics, with the return of former players, is becoming increasingly likely — as indicated by a series of 2017 mutinies that revived memories of a country split between the Ouattara-controlled north and Mr. Gbagbo’s southern strongholds. Moreover, recent events suggest that for political decision makers, the presidency seems to remain the only game in town. That makes the upcoming elections a potential zero-sum game, in which regional cleavages and patronage dynamics may prevail over governance.

Eternal return?

While Alassane Ouattara does not fit the “president for life” stereotype, the prospect of him running for a third term has become more likely. While the constitution establishes a two-term limit, it is possible to argue that the 2016 constitutional change reset the count, allowing him to run again in 2020 (and in 2025). The fact that he has postponed a decision until the beginning of 2020 suggests he will run if he decides that power may fall in the wrong hands.

President Ouattara’s chosen successor would be Prime Minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly, a close ally and a fellow technocrat. However, the fact that Mr. Gon Coulibaly is a low-profile politician lacking Mr. Ouattara’s charisma casts doubt on whether he could win a presidential runoff, especially if the opposition forms a coalition opposing him. But while there are indications that such a negative coalition is being formed, it is still not clear who will lead it.

Guillaume Soro was the first to announce his candidacy. Despite being relatively young (at the age of 47), Mr. Soro has an extensive background of both conventional and unconventional experiences. Besides serving as prime minister under former president Gbagbo and President Ouattara and as president of the National Assembly, he was also the leader of the rebel forces that occupied the north until 2011. Trying to distance himself from his rebel past, Mr. Soro has created the Generations et Peuples Solidaires movement. His vague, mostly social media-based campaign has focused on the need for generational turnover, reconciliation and engagement with the diaspora.

Another probable (though still unconfirmed) candidate is Henri Konan Bedie, president from 1993 to 1999, who has abandoned the RHDP coalition to become the face of the opposition to Mr. Ouattara. But he may be entering into a new alliance, which could destabilize the country’s political and security outlook.

While Mr. Ouattara does not fit the “president for life” stereotype, the prospect of him running for a third term has become more likely.

In July, Mr. Bedie visited former president Gbagbo in Brussels (where he remains on conditional release) and both agreed that the PDCI and Mr. Gbagbo’s Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) would “work together on specific objectives for the 2020 presidential election.” In other words, while each party would have its candidate in the first round, they plan to unite forces against the ruling RHDP in a runoff scenario. In September, even though both leaders are outside the country, the two parties held a joint rally in the capital Abidjan, with an estimated 10,000 participants.

However, aside from their shared aversion to President Ouattara, the leaders of this alliance have little in common. The political profile of former Mr. Gbagbo – in line with other leaders of postindependence Africa – reflects a combination of socialism, anti-imperialism and (sometimes aggressive) nationalism. Despite being the man responsible for the violence that occurred in 2010-11, which led to the death of 3000 people, Mr. Gbagbo still has a significant base of support, as evidenced by the enthusiastic reaction to his acquittal at the ICC. A past of mutual hostility and the lack of common ideological ground between Mr. Bedie and Mr. Gbagbo suggest that the opposition to President Ouattara and the RHDP may be more anchored in personal ambitions, resentment and patronage than in the construction of an alternative agenda.

Scenarios

Despite the sustainable progress attained over the last eight years – especially on the economic front – Ivory Coast seems to find itself between a rock and a hard place. Under any scenario, the upcoming year will be eventful, with elections scheduled for 31 October 2020. There will be consequences for the country’s political, security and economic outlooks, as uncertainty regarding candidates and potential alliances, and an expected increase in social contestation will likely affect investors’ decisions.

Three main scenarios must be considered. Under the first, slightly more likely projection, Alassane Ouattara – pressed by his party and resorting to a particular interpretation of the constitutional order – will announce his presidential candidacy in early 2020. More political polarization will follow as the opposition contests the constitutionality of Mr. Ouattara’s bid, which may compromise his political legitimacy. However, despite its intolerance of illegal power grabs, the judicial complexity of the situation and President Ouattara’s regional leverage suggest that the Economic Community of West African States would not take a firm stand against such a move. Under this scenario, instability and violence would likely occur in the likely event of a runoff between Mr. Ouattara and Guillaume Soro or Henri Konan Bedie, as remaining opposition parties and leaders (including Laurent Gbagbo) would rally behind the current president’s eventual opponent.

Under the second, less likely script, President Ouattara would remove the 85-year-old Bedie from the race, by introducing age limits through a constitutional amendment. In this case, Mr. Ouattara would also leave the race, and the RHDP candidate could be Prime Minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly. While this scenario would avoid the revival of old cleavages associated with the “eternal return” hypothesis, instability would still remain likely in case of a runoff between the RHDP candidate and Guillaume Soro. That man, despite his young and liberal appeal, still has the capacity to unleash violence via informal networks. Also possible under this scenario is President Ouattara, ahead of the elections, resorting to the recently created post of vice president to integrate parts of the opposition in the RHDP.

Under a third, rather unlikely, scenario, Laurent Gbagbo would join the presidential race. While Mr. Gbagbo has been cleared of crimes against humanity, the ICC’s chief prosecutor has appealed the ruling and the former president is now in Belgium, awaiting the end of the process. His lawyer has recently asked the ICC to “immediately and unconditionally free him,” stating that he should be allowed to participate in the 2020 elections. Considering the fragility of the peace process, the persisting strength of both conventional and unconventional armed forces and the polarization generated by his candidacy, this scenario would likely have strong negative consequences, reversing the path of stabilization and growth initiated in 2011.