In Peru, the pace of progress slows

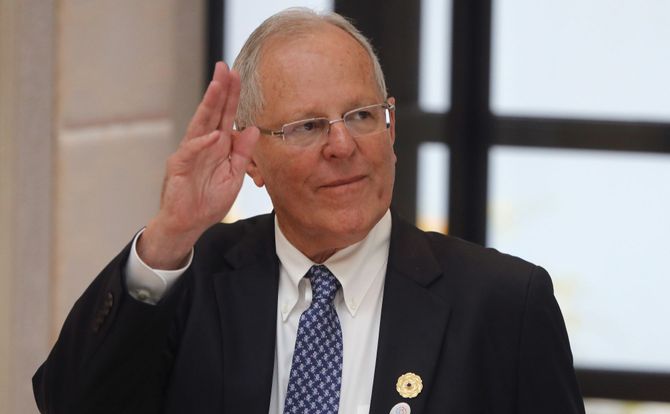

In Peru, President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski is wrangling with a fractious, majority-opposition congress. Having just narrowly escaped impeachment proceedings, he offered a presidential pardon to the controversial former President Alberto Fujimori.

In a nutshell

- Political turmoil has hamstrung the government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski

- He has made a risky move by pardoning a controversial former president

- The fate of his government is tied to the prices of the commodities Peru exports

In 2017, Peru’s economy and political system were subjected to disruptions both natural and man-made: severe flooding crippled the country and caused widespread damage throughout the spring, while the continent-wide Odebrecht bribery scandal has led to criminal charges against a stunning proportion of Peru’s political elite, including three former presidents. Meanwhile, President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s 15-month old government has been repeatedly hamstrung by an unsupportive congress that by December had threatened him with impeachment.

Flooding throughout March in Peru’s coastal areas, particularly in the northwest of the country, left nearly 150 dead and 700,000 homeless. Crucial transportation corridors were knocked out of commission, which in turn caused mineral exports, the bedrock of Peru’s economy, to grind to a halt. It is estimated that the floods cost Peruvian gross domestic product (GDP) at least 1 percentage point of growth this year, and the price tag for recovery will likely surpass $8 billion.

Odebrecht scandal

Meanwhile, scandals surrounding the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht have led to further economic stoppages and political woes. An ever-expanding web of bribes and backdoor payments has been discovered in Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and Peru. Odebrecht is now understood to have illegally arranged over 100 deals in 12 countries with nearly $800 million in bribes, producing over $3 billion in ill-gotten profits.

When the scandal broke in Peru early last year, President Kuczynski (known as PPK) called a halt to several local Odebrecht projects, including a major oil pipeline. The resulting standstill led to a further economic slowdown in the second quarter of 2017 and complicated Mr. Kuczynki’s efforts to fuel growth with public infrastructure projects, since Odebrecht has been the recipient of numerous contracts over the past decade.

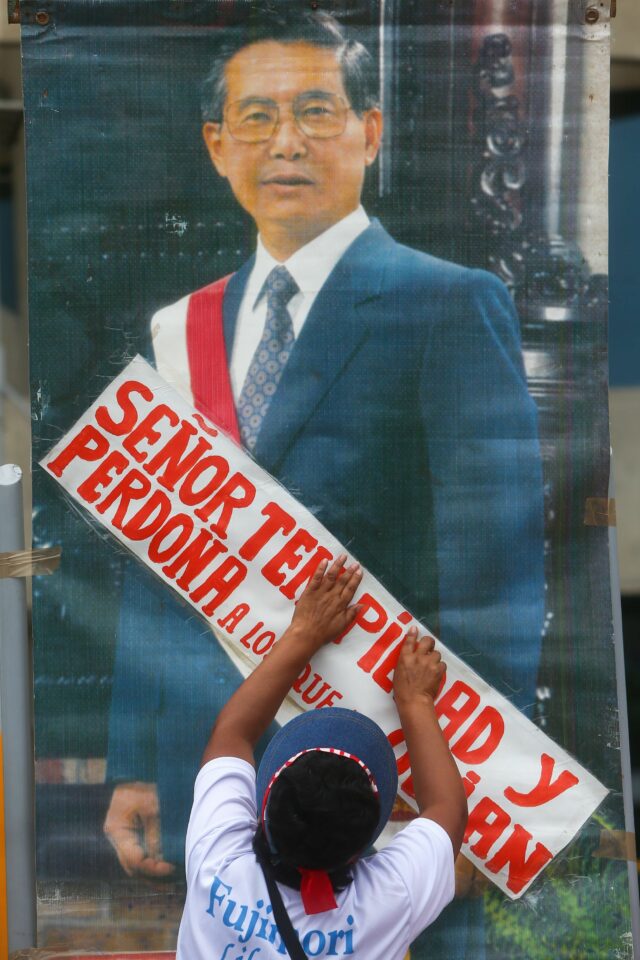

Three former presidents have been implicated in a continent-wide corruption scandal.

The political consequences of the Odebrecht scandal have been at least as far-reaching. Several Peruvian officials have been implicated in Odebrecht’s bribery scheme, including three former presidents. Ollanta Humala (2011-2016) and his wife have been arrested on money laundering charges that relate to Odebrecht. Meanwhile, Alejandro Toledo (2001-2006) has been charged with even greater collusion with the Brazilian company, but has avoided arrest by fleeing to the United States, where he has mounted a public relations campaign in the press and social media protesting his innocence. He stands accused of having accepted more than $20 million in payments, and the charges provoked suspicions against President Kuczynski, who served as Mr. Toledo’s prime minister and finance minister.

Additionally, Peruvian public prosecutors have opened a case against former President Alan Garcia (1985–1990, 2006–2011) for financial irregularities involving Odebrecht’s construction of the Lima subway system during his tenure. Already, five Garcia-era ministers have been arrested on related charges. With a fourth former president, Alberto Fujimori (1991-2001), already imprisoned in Peru for human rights violations and corruption, it is safe to say that the Odebrecht scandal will have lasting implications for trust in public institutions in Peru.

Uncooperative legislature

Although PPK has not been ensnared in the corruption scandal, his administration’s ability to govern has been limited by an uncooperative legislature in which the opposition party, Popular Force, holds 71 of 130 congressional seats. In 2016, PPK was elected by a razor-thin margin of victory over Keiko Fujimori, head of Popular Force and daughter of former President Alberto Fujimori. In that race, Mr. Kuczynski won 21.1 percent of the vote in the first round, well short of Ms. Fujimori’s 39.9 percent.

In the second-round runoff, however, he eked out 50.1 percent of the vote, gaining the presidency by a margin of 40,000 votes out of 17 million cast. PPK essentially triumphed by virtue of being anyone but Ms. Fujimori. His party fared considerably worse in the legislative elections, though, winning just 14 percent of congressional seats. It was clear from day one of his term that PPK would have serious hurdles to overcome to pass any meaningful legislation.

Ms. Fujimori’s Popular Force lost no time in throwing wrenches into the Kuczynski government machinery, primarily by removing members of the president’s cabinet using mechanisms available to them under Peruvian law. The situation came to a head in September, when opposition efforts to remove President Kuczynski’s second education minister (he dismissed his first education minister just four months into his presidency) culminated in a vote of no confidence for the entire cabinet.

In response, PPK replaced his prime minister, naming Mercedes Araoz his new head of government. Ms. Araoz, in turn, reappointed 13 of President Kuczynski’s cabinet members, but replaced five – most notably the heads of the education, health, and justice ministries – with officials more likely to appeal to the Fujimorista opposition. Moreover, Ms. Araoz is widely respected across the political spectrum.

The no-confidence vote undoubtedly bolstered the widespread impression that PPK is weak, a sort of lame-duck president who still has four years left in office. And his approval ratings have dropped below 20 percent. But his position has also strengthened in one way. If the Fujimorista opposition decides to call another no-confidence vote, Peruvian law allows Kuczynski to dissolve congress entirely and call new elections. With such an overwhelming majority already established in Congress, Popular Force has no incentive to risk what it has achieved. Instead, they will bide their time, and hope to take the presidency from Kuczynski in 2020.

Impeachment and Fujimori pardon

The question consuming the Peruvian political class in 2018 will be the presidential pardon for former President Alberto Fujimori issued the day before Christmas 2017. The pardon is an extremely delicate maneuver for PPK, given that his election relied on a coalition of voters that agreed on just one thing: the corrupt, authoritarian legacy of “fujimorismo” needed to be relegated to the past. Pardoning Mr. Fujimori – something his own daughter, Keiko, promised not to do in her campaign – could alienate the extremely amorphous and disparate base that PPK relies on to govern.

The pardon came following PPK’s narrow escape from impeachment when Kenji Fujimori, the younger brother of Keiko, broke with his sister and brought his bloc to support the president. The ostensible reason for the impeachment request was a consulting fee paid to Westfield Capital Ltd, a U.S. firm that PPK had started during his years as a banker in the U.S. PPK claimed that the fee was paid without his knowledge and that he had had nothing to do with the transaction. Whatever the truth, much of the public saw the transaction as evidence of the same type of corruption that his predecessors are suspected of.

The split between the two Fujimori children could win PPK some support from the opposition.

Upon his release, Alberto Fujimori asked for forgiveness from the Peruvian people and called for national unity. It is possible that the split between the two Fujimori children could win PPK some support from the opposition. The differences in program between Mr. Kuczynski’s followers and Popular Force are, in fact, minimal. Both groups largely accept the neoliberal, free-market policies that defined the Fujimorista platform.

There are certainly policy areas in which collaboration seems possible, including infrastructure investment and increasing participation in the formal economy. Only a quarter of Peru’s labor force is active in the formal economy; PPK has outlined a goal of achieving 50 percent participation by 2021, primarily by relaxing rigid labor laws that make informal hiring desirable.

The cracks in Popular Force, by far the strongest political party in Peru, might open the path for Kuczynski’s party, Peruvians for Change (whose intentionally misspelled Spanish name, Peruanos Por el Kambio, shares his initials: PPK) to return to power in 2020, when PPK will be 82. On the other hand, the pardon infuriated the political forces on the left and led more than half of the cabinet to resign in protest. PPK will have to reconstitute his cabinet and his tiny party to form a base from which to negotiate with the Fujimori clan.

Economic prospects

Economic growth dipped in 2017, but is expected to improve this year. Peru’s central bank estimates GDP in 2017 grew by about 2.8 percent, down from 3.9 percent in 2016. The third quarter of 2017 showed improvement, with both private and public investment rebounding. Growth expectations for 2018 are around 4 percent, with a boost from increasing copper prices and a strong mining sector.

In early November, the government reached an accord with indigenous communities to continue oil extraction in the Block 192 region, on the Ecuadorian border. The area is the source of nearly 20 percent of Peru’s oil. Operations had been halted for several months as the communities protested their lack of voice in the process, the absence of adequate health care and compensation, and the environmental harm created by the drilling.

Peru’s growth numbers are disappointing compared to the 6 percent growth it recorded in 2012.

However, all of Peru’s growth numbers are disappointing compared to the 6 percent growth it recorded in 2012, before global commodity prices collapsed. Copper, zinc and gold make up over 60 percent of Peru’s exports, so its fortunes wax and wane with their prices. To the relief of both Peru and neighboring Chile, the price of copper is on the rise.

In other sectors, such as logging, the government has struggled to rein in illegal activity in regions with minimal state presence, and the U.S. has recently moved to block certain Peruvian timber imports due to their dubious provenance. For Peruvian goods to retain their credibility in the global marketplace, President Kuczynski will need to expand his efforts at economic formalization and anti-corruption into these sectors.

Foreign policy

PPK has enhanced his credibility by taking a strong stand against the increasingly authoritarian Venezuelan government. Working with his former foreign minister, Ricardo Luna, PPK has hosted international meetings seeking regional consensus on how to deal with the deteriorating situation in Venezuela. The new foreign policy chief, Cayetana Aljovin, who previously held the positions of minister of energy and mines and minister of development and social inclusion, is expected to continue this assertive policy and add a modicum of progressive perspective to the cabinet.

He also has asserted regional leadership in the negotiations between China and Peru’s neighbors to bring the ambitious project of a transcontinental railroad to fruition.

Scenarios

Scenarios for Peru’s future hinge on two questions. The first is the global commodity market. If prices continue to rise – and indications are that they will – President Kuczynski will be well-placed to implement his strategy of infrastructure projects and economic inclusion, while also overseeing a period of robust growth.

But that will depend on his ability to get legislation through the congress. Now that he has pardoned Mr. Fujimori, he will count on support from a faction of Popular Force, which would help push through economic reforms that both sides can agree on. This is a high-risk strategy that brings no guarantee of success in the remaining years of PPK’s term in office. He does not appear to have any alternative in the coming year. With every increase in the price of copper on the international market, PPK will have more room to maneuver both with the fractious congress and with the modernizers in his party and his cabinet.