China finds investment in Kyrgyzstan a risky necessity

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become a boon to Kyrgyzstan. There are big plans for the future, but also troubles on the horizon. Mounting anger over China’s predatory practices as a lender and investor, and concern for the abused Muslim Uighurs in China, have fed nationalistic, anti-China sentiment among the Kyrgyzstan population.

In a nutshell

- Bishkek’s and Beijing’s “strategic partnership” started in 2013 with the BRI infrastructure project

- Kyrgyzstan’s location allows shorter overland routes through mountainous terrain

- China owns nearly half of the Kyrgyz foreign debt and realizes the risk of further exposure

There was a time, in the early 1990s, when Kyrgyzstan – officially the Kyrgyz Republic – was depicted by some outside observers as Central Asia’s Switzerland. It was not only the Tian Shan mountain range, one of the most spectacular in the world, that attracted praise. Far more important was the belief that progressive domestic leadership, assisted with foreign investment and generous assistance, would allow the distant mountain republic, then inhabited by only four million people, to emerge as an economic and political success story.

A quarter-century later, Kyrgyzstan retains a well-earned reputation for natural beauty. The visions of economic and political success have long since been forgotten. As Western governments and donors withdrew their support and Russia’s role diminished, the country became beholden to China. Since the rollout of its massive infrastructure construction program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Middle Kingdom has become Kyrgyzstan’s largest trading partner and second largest investor.

While both sides emphasize that the future looks bright, there are good reasons to be skeptical. The downside for Bishkek is that China’s growing influence has caused increasing popular resentment. Beijing’s potential risk is that massive corruption in Kyrgyzstan, associated with lavish Chinese credits, is feeding into domestic politics and may seriously destabilize an already volatile situation.

Opportunities and risks

China owns nearly half of Kyrgyzstan’s foreign debt ($1.7 billion of the $3.8 billion total in 2018). Extending further credits will inevitably increase Beijing’s exposure to credit risk. With a gross domestic product (GDP) of just above $7 billion, the country’s debt ratio has not yet reached critical levels, but the contours of a financial trap are becoming visible.

Even so, there are significant grounds for optimism. Unlike neighboring Tajikistan, where BRI investments are mainly concentrated in the energy sector, the program for Kyrgyzstan also entails serious transport infrastructure. One example is the north-south motorway, currently under construction, to link the capital city of Bishkek in the north with Osh, the country’s second-largest city, in the south. Another key transport project, the long-discussed China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad, may soon be getting underway.

Kyrgyzstan is the closest to parliamentary democracy that you can get in the region.

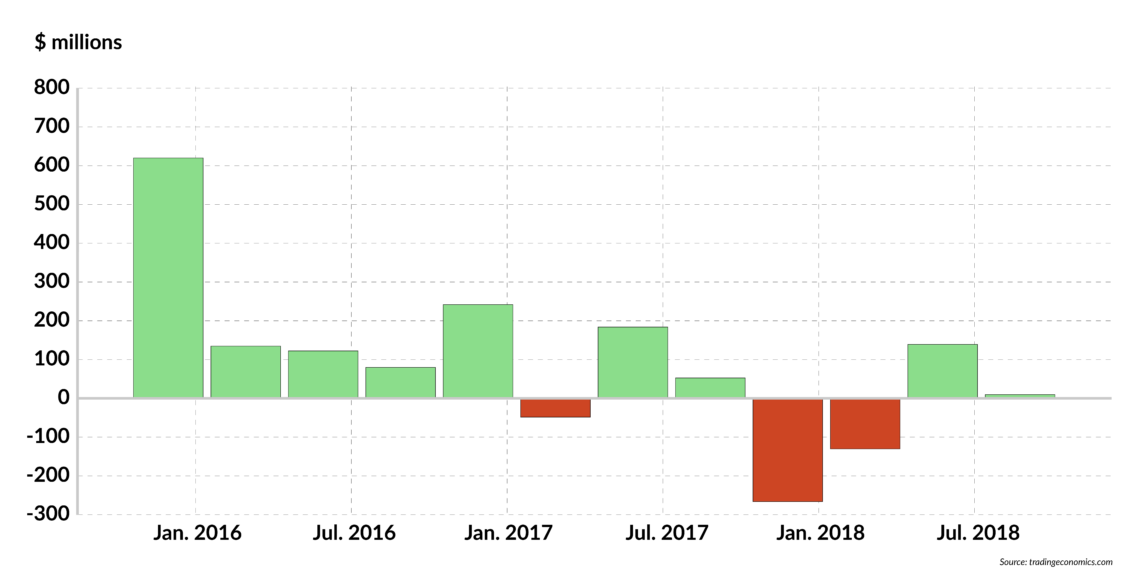

The risk profile for China in these ventures, on the other hand, is made worse by the fragility of the Kyrgyz economy. The country’s GDP per capita is $3,667, compared to $26,252 in Kazakhstan. Some 30 percent of this total is not generated at home but made up of remittances from the one million Kyrgyz working abroad, mostly in Russia. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has also dried up, with the inflow shrinking from $1.14 billion in 2015 to just $94 million in 2017.

While Kyrgyzstan is still the closest to parliamentary democracy that you can get in the region, endemic corruption and political instability, driven by conflicts between rival clans, add to systemic fragility. Two presidents have been deposed and forced to flee the country in violent rebellions: Askar Akaev (1990-2005) and Kurmanbek Bakiyev (2005-2010). The national parliament is often described as a marketplace for transacting corrupt deals. In Transparency International’s 2018 Corruption Perception Index, Kyrgyzstan is ranked 132nd out of 180 nations.

Turning point

The takeoff in relations with China occurred in 2013, when President Xi Jinping announced the BRI. Getting together on the sidelines of a Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting in Bishkek, President Xi and then Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev agreed to elevate the two countries’ links to a “strategic partnership.”

Facts & figures

Silk Road in Kyrgyzstan

The evolving relationship got an indirect boost in 2014, when the Kyrgyz government, under heavy pressure from Moscow, closed the Manas air base to the United States Air Force. The facility, which began operating in 2001 at the Manas International Airport, had served as a staging post for the U.S. military operations in Afghanistan. In exchange for its use, the American side paid a substantial rental fee, while USAID and other donors developed ambitious assistance programs for Kyrgyzstan. These money flows stopped with the installation’s closure, creating a void that China was only too glad to fill.

Kyrgyzstan’s current president, Sooronbay Jeenbekov (elected in November 2017), has set out to repair frayed relations with neighboring Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and he is also seeking closer ties with Turkey. Yet these overtures fade beside the importance of Kyrgyzstan’s strategic links with China.

At a June 2018 meeting between Mr. Jeenbekov and President Xi in Beijing, bilateral relations were described as at their “highest level in history.” In addition to cooperation on trade and economic issues, the two countries’ “comprehensive strategic partnership” provided that neither side would join any organization that might undermine the other. Bishkek also affirmed its support for Beijing’s paramount One-China policy.

Anti-China backlash

One potentially disruptive element is the growing popular discontent with China’s expanding influence in Central Asia. Two protest rallies held in Bishkek in January 2019 brought the message home. The demonstrators’ demands included deportation of illegal immigrants, restricting citizenship to ethnic Kyrgyz and inspections of companies that employ Chinese labor.

A contentious aspect of Sino-Kyrgyz relations is also the plight of the Muslim Uighurs in China’s Xinjiang province.

Following the first rally on January 7, the government warned that any attempt by activists to sour the relationship with China would be dealt with sternly. Following the second protest 10 days later, the state announced new legislation on job protection, a 20 percent cap on employment of foreign nationals by local companies, and a financial levy on all firms hiring foreign workers.

It bears noting that talk of Chinese migrants flooding the country tallies poorly with official visa statistics. The organizers behind the rallies – a group calling itself Kyrk Choro (Forty Knights), instantly recognizable for wearing kalpak felt hats, the traditional Kyrgyz headgear – has made a reputation for incendiary nationalist stunts. That said, popular discontent is on the rise and may prove difficult for the authorities to contain.

A more awkward challenge to the local establishment are demands for audits on how the Chinese loans have been secured and spent. Disclosures in this area could prove embarrassing to many Kyrgyz officials, given China’s practice of predatory lending.

Anti-corruption probes have already unearthed plenty of irregularities. One instance involves an $850 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China for the Bishkek-Osh motorway. On receipt of these funds, sources say, officials associated with then Prime Minister Sapar Isakov (2017-2018) colluded with the contractor, the China Road and Bridge Corporation, in inflating construction costs by several orders of magnitude.

Facts & figures

Kyrgyzstan Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) net inflows

Another case is a $386 million contract awarded without a proper tender to a Chinese company, the Tebian Electric Apparatus Stock Co., Ltd. (TBEA Co.), to overhaul the Bishkek Thermal Power Station. The loan financing was again provided by the Export-Import Bank of China, which is active across Central Asia. When the plant malfunctioned in January 2018, leaving residents of the Kyrgyz capital without heating for four days in temperatures close to 30 degrees below zero, the ensuing outrage led to the arrest of two former prime ministers, the aforementioned Mr. Isakov and Zhantoro Satybaldiyev (2012-2014).

A contentious aspect of Sino-Kyrgyz relations is also the plight of the Muslim Uighur population in China’s Xinjiang province. As international attention to Beijing’s crackdown on Uighurs has intensified, and United Nations reports warn up to one million people being abused in “reeducation camps,” Central Asian governments have preferred to look the other way.

Balancing act

Following the January 7 Bishkek rally, which raised the Uighur issue, Kyrgyz officials maintained that accounts of persecution in Xinjiang had been overstated. A Foreign Ministry press release said the alleged detention camps were “vocational education and training centers.” The fact that increasing numbers of ethnic Kazakhs and Kyrgyz have also been victimized in China’s system of repression is making the government’s position increasingly difficult to maintain.

The danger this explosive issue poses for Bishkek has been illustrated by Beijing’s swift and forceful response to Turkey after President Recep Tayyip Erdogan allowed his foreign ministry to rebuke China by calling the detention camps “a great shame for humanity.” Turkey shares linguistic and cultural similarities with the Uighurs and harbors many refugees from Xinjiang.

It was symptomatic that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, on a recent visit to Beijing, defended China’s right “to take counterterrorism and de-extremism measures to safeguard national security.” The crown prince then proceeded to sign $28 billion worth of deals. There is no question that China takes the Uighur question very seriously.

Scenarios

Despite these storm clouds, the Beijing rollout of the BRI appears to be on track. One reason is that Russia’s potential to act as a regional counterweight to China has been eroding.

Russian influence wanes. Cultural and linguistic ties still work in Moscow’s favor. Kyrgyzstan has the highest percentage of Russian speakers in Central Asia, and the Russian language is granted higher official status and greater respect there than in any other Central Asian country. And yet, there have been calls in Kyrgyzstan for legislation to remove this special status and enhance the role of the Kyrgyz tongue. This proposal is popular despite the apparent risk of prodding many of the country’s 500,000 Russian-speakers to leave, shrinking the pool of skilled labor.

The Ministry of Education recently ordered that people with documented proficiency in Kyrgyz be given preferential access to postsecondary education, a move that will close the path to career opportunities for some Russian speakers.

Kyrgyzstan’s membership in the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) is another asset for Moscow, providing a theoretically valuable edge in trade relations. But the downturn in the Russian economy has greatly reduced the attractiveness of EEU membership, and a simple comparison of its modest benefits with the BRI’s enormous financial muscle clinches the argument.

The key remaining Russian asset is the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which positions Russia as the key provider of security for Kyrgyzstan. Russia also operates an air base at Kant, in northern Kyrgyzstan. But the Kremlin’s ambition to enhance its military presence with a second base, following its pattern of beefing up forces in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, has made little progress.

During 2018, there were rumors about Russian-Kyrgyz talks on a second base. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov signaled his openness to discuss the subject during a visit to Bishkek in February 2019. Only days later, however, the head of the Kyrgyz Security Council announced that the issue was not under consideration. The likely explanation is that Russia has been unwilling, or unable, to come up with sufficient financial inducements.

China presses on. Kyrgyzstan’s claim to attention lies in its location on a key segment of the Silk Road. There are huge upsides to all concerned from less circuitous transport routes over mountainous terrain. However, these shortcuts also entail significant risks. The eventual success of the BRI is to no small extent contingent on Kyrgyzstan’s political situation, which is fragile. The anti-corruption probes recently launched by the Kyrgyz government for local consumption may end up exposing China as a sponsor and facilitator of the political elite’s ill-gotten gains.

Beijing may believe it stands to gain from loaning money that shaky governments may not be able to pay back. Indeed, China has made no secret about taking short-term advantage of cash-strapped countries, which have been forced to sign away natural resources, vital infrastructure and even territory. The downside is that China’s associated policy of noninterference in domestic politics, including turning a blind eye on corruption, may backfire now that it has extensive economic interests on the ground.

Serious embezzlement is said to have been standard practice under the six-year tenure of former President Almazbek Atambaev (2011-2017). Bishkek’s current anti-corruption drive may be viewed as a way for the new president to assert his power against the clique associated with his predecessor. But if this drive results in Beijing being held co-responsible for massive corruption among the domestic elite, it could trigger further outbursts against Chinese migrants and the crackdown in Xinjiang province.

These processes bear watching. Interestingly, Huawei Technologies recently opted out of an ambitious investment program, to be co-funded with China Telecom, that was supposed to transform Bishkek and Osh into “smart cities” with fast internet and extensive monitoring systems. The project would have further enlarged China’s economic footprint in Kyrgyzstan.

One encouraging development for Beijing has been a noticeable rise of China’s cultural and humanitarian profile. There are now four Confucius Institutes in Kyrgyzstan. Thousands of local residents are learning Chinese and many hope to study in China. Combined with the raw financial muscle of the BRI, this influence should keep the outlook positive for China’s interests in the region.