Prospects for Latin American economies in 2019

Latin America’s economies are facing a series of problems in 2019. Countries that failed to prepare for the current downturn in prices deal with a loss of revenues and foreign investment. Corruption and quality of life issues have presented other challenges, and the benefits of a recent trade deal with the EU are neither immediate nor assured.

In a nutshell

- The region’s economies face common problems this year

- Low prices are exposing an overdependence on commodities

- Foreign investment lags, and domestic issues like corruption make policy solutions more difficult

Talking about a region as diverse as Latin America has its perils. With that warning in mind, there are a few generalities that can help us understand what is happening in the Western Hemisphere south of the Rio Grande. These generalities can be thought of as a statistical mean, revealing the countries deviating from these trends that might have better or worse prospects for dealing with the region’s common problems.

Overdependence

A striking feature of the current situation in Latin America is a broad dependence on the production and export of primary materials: the resource curse. Only Chile and Colombia have reacted to the boom in commodities prices over the last decade by setting up national reserve funds to protect against the inevitable downturn in prices. Chile’s reserve was exhausted after a year of the government drawing from it, and Colombia never got around to stashing any money into its fund. The geopolitical issue here is the vulnerability of a country to an external situation over which it has little or no control. Commodity prices are notoriously cyclical, which poses the question – what will you do when prices fall?

During the commodity boom, the only countries that instituted policies to diversify the economy beyond raw materials were Mexico and Brazil. (And Mexico relies heavily on links to the United States, which, under President Donald Trump, carry their own form of risk from external events.) On the other hand, all of the countries in the region took advantage of the price boom to create or expand existing generous social welfare programs, many of which were targeted at potential voters.

With the end of the boom at the beginning of this decade, and the sudden end or decline of such programs, there have been anti-government backlashes in several countries, particularly Venezuela and Argentina. The economies of both countries actually contracted in 2018 and Venezuela’s will do so again in 2019, while Argentina may avoid doing so by the slimmest of margins. In Venezuela, the most exuberant example of social spending was former president Hugo Chavez delivering one million washing machines to his followers in the shanty towns around Caracas. Today, the government of his successor, Nicolas Maduro, cannot keep electricity or water flowing into those shanties to run the washing machines.

Seeking investment

The decline in commodity prices has been a double whammy for Latin America because the potential buyers of those products, who are also the potential investors in the region, have been distracted by cheap money and their countries’ sluggish growth. Historically low interest rates in Europe and the U.S. have persuaded investors to keep their money in hard currency countries rather than accept the higher risks and higher returns that come with South American debt. It remains the case that the countries formerly called “underdeveloped” or “developing” all need capital, whether via buyers of their public debt or from foreign direct investment (FDI). The lack of FDI over the past year has been perhaps the most significant headwind keeping the region from making economic progress.

Low interest rates in Europe and the U.S. have led investors to keep their money in hard currency countries rather than accept higher-risk South American debt.

In the current external context, the collapse of Odebrecht, the largest construction company in Latin America, has magnified the influence of multilateral banks such as the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF), the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), and the Chinese-dominated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The CAF is playing the most important role, with $24 billion in loans made – twice the amount lent by the IADB and five times what the AIIB has put into the market.

With Odebrecht’s collapse, countries in Latin America seeking loans or investment capital must operate through the state and adhere to standards imposed by the lending institution, doing without the $800 million in bribes paid out by Odebrecht to get infrastructure projects over the last decade. In the case of the CAF and the IADB, this means significant attention must be paid to the environment and to issues of inclusion. These standards can, especially in the case of mining on lands claimed by indigenous people or in the Amazon, provoke civil conflict, which puts stresses on very weak states. The lack of state capacity is also apparent in the difficulty some countries have in formulating coherent development plans to satisfy the requirements of the lending institutions. Previously, neither Chinese state agencies nor Odebrecht paid much attention to national development plans.

Quality of life

There is another problem with commodity-driven growth, one that has particular consequences for the internal context of countries in the region. As gross domestic product (GDP) increases, as it has for most of the countries in the region over the past decade, there is a growing lag in what is called “well-being outcomes” by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

The region outperforms expectations, given its GDP per capita, in terms of life expectancy, primary education coverage, social connection and air quality. On the other hand, violence and income inequality remain relatively high, the prevalence of “off-the-books” jobs or activities is still a problem, and real wages have increased at a slower pace than in other countries with similar GDP per capita. Moreover, labor productivity has declined over the past decade, relative to OECD countries.

These are problems with immediate political repercussions. In reviewing the economies of Latin America, the OECD referred to four “new” development traps: the productivity trap, the social vulnerability trap, the institutional trap and the environmental trap. These are domestic problems, not associated with the external context, and while they can be ameliorated by well-targeted domestic policies, such policies are difficult to formulate in weak states.

Facts & figures

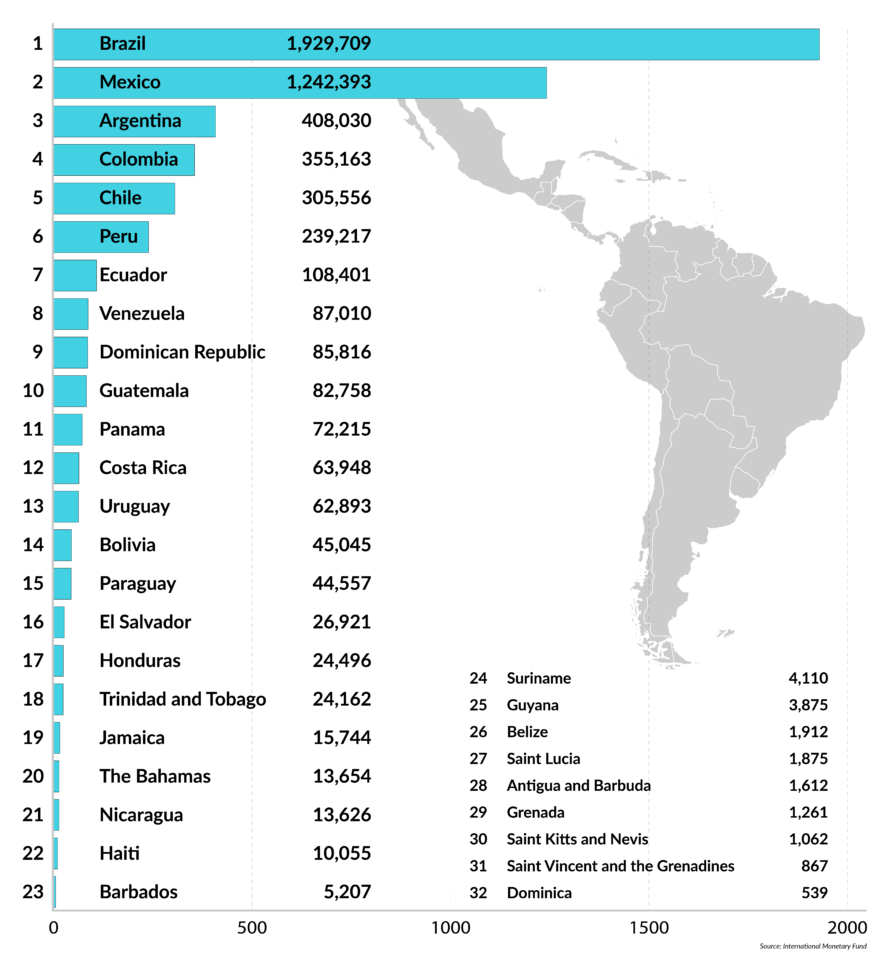

Latin America and the Caribbean, nominal GDP

millions of $US

Trade deals

It is tempting to consider the recent trade agreement between the European Union and Mercosur a game-changer. However, before we wax too enthusiastic, we must remember that the pact must first be approved by governments on both sides of the deal. Second, while there is no doubt that the agreement is a strong statement in opposition to the rise of protectionism, it is by no means a declaration of free trade between the two groups.

Lastly, assuming the agreement is ratified, most of the real progress in the short term will be in the increased sales of primary products by members of Mercosur to EU countries. What the agreement makes possible in the long term is more trust between the two parties, leading to greater investment by Europeans in South America. That, indeed, would be a significant boost for the Mercosur region.

One model for how trade agreements can boost economic growth is the Alliance of the Pacific, which includes Chile, Peru, Colombia and Mexico. The formal agreement makes little mention of specific goods, whether primary or manufactured, focusing instead on the process of trade. At first glance these appear to be very modest steps, but they improve the domestic (state) capacity of the participants, make bureaucratic and regulatory rules more transparent, and buttress the institutions involved in each country.

The Alliance has served to increase trade without altering the existing tariff structure among the participants, mainly by decreasing the transaction costs of doing business and building trust among members. Dealing with tariffs will come at a later stage for the Alliance countries. Meanwhile, increased efficiency and transparency make the participating countries more attractive to potential investors.

Internal corruption

While the external context has not been favorable to Latin America, the internal context has been positive in some cases and negative in others on the issue of economic growth. Corruption and a weak regulatory framework are important inhibitors of FDI. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, the highest-ranking country in Latin America is Uruguay, at 23. Close behind is Chile, at 27, and both countries enjoyed a good year in 2018 (although both are relatively small economies).

By contrast, among the larger economies, we find Brazil at 105 on the Transparency International index, Mexico at 138, and Argentina at 85. These countries, which would hope to attract significant amounts of FDI, are much less appealing because of the complications created by endemic corruption. To compound their difficulties, both Argentina and Brazil are going through periods of political instability.

Certain aspects of state capacity are significant factors in whether a country can formulate effective development policies. If corruption is an indicator of state weakness, so too is a lack of revenue. If you can provide for your citizens’ welfare only when the price of your principal export is high, you are in trouble.

Facts & figures

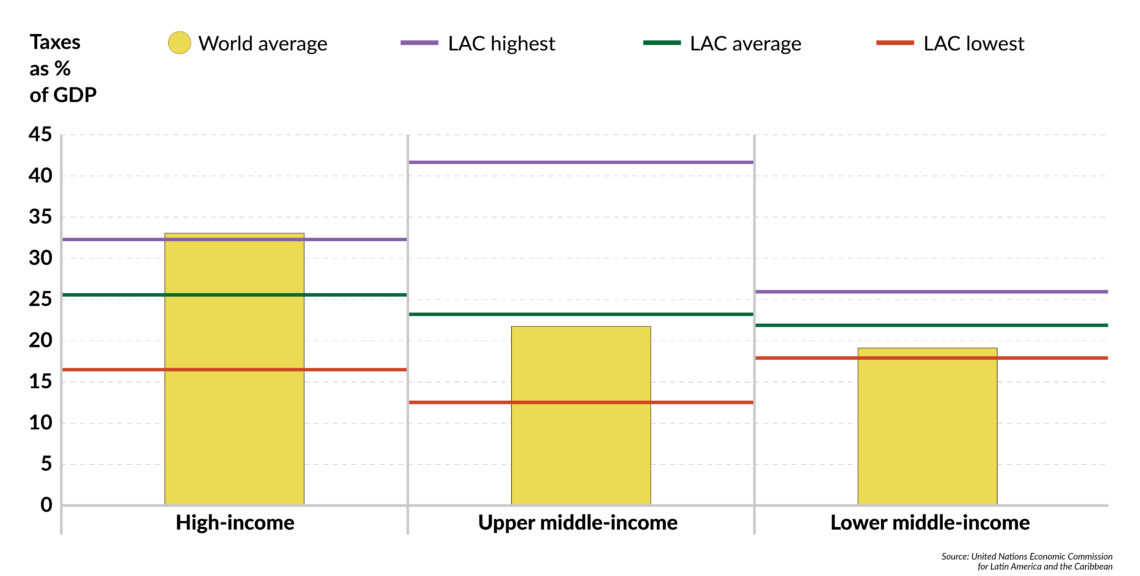

Tax-to-GDP ratios in Latin America and the Caribbean by income group vs. world averages

A good indicator of a state’s capacity and an index of the will and commitment of the country’s political leaders’ to seek the revenues necessary to govern is the taxes collected by its government. The countries of Latin America do not tax their people much. Chile and Colombia, both members of the OECD, are the two members with the least amount of taxes collected. For other countries in the region, like Brazil and Argentina, the comparison to some of the more advanced countries in northern Europe is even more striking. Collecting taxes and maintaining a coherent regulatory framework are critical preconditions to attracting FDI.

Scenarios

There are glimmers of hope for several Latin American countries. A few of the smaller economies, notably Uruguay and Costa Rica, have kept their houses in order through fiscal prudence, relative transparency in their regulatory frameworks and rule of law. They should be able to attract the FDI they need in the coming year. It is not an accident that both of these countries have also begun to prepare their labor forces for the challenges of globalization and to provide incentives for innovation.

Among the larger economies, Argentina has done the most to prepare for the new challenges. Unfortunately, the current government has not been able to deal with the mess left behind by its predecessor. Still, President Mauricio Macri has the country moving in the right direction, and in the coming year, Argentina should see a return to growth. Whether this positive turn will come in time to save Mr. Macri in the October elections remains to be seen.

In Brazil, the region’s largest economy, the question is whether the new president, Jair Bolsonaro, can get pension and tax reforms through congress. Brazil is poised for a surge in growth – perhaps the only country in the region with an adequate supply of domestic capital – and is waiting for its political leaders to get their collective act together.

Among the middle-size economies, Chile and Peru are doing the best and should enjoy significant growth in the coming year. Chile has the advantage in attracting FDI because it has shown a willingness to contain corruption and make its regulatory framework more transparent. The current government in Peru has made the battle against corruption its principal objective. It does not hurt either of these two countries that the prices of their principal exports, copper and other metals, are stable at levels that provide the government with revenue.

For those who enjoy risk, there is sovereign debt for sale. Goldman Sachs was shown last year to be bottom-feeding on distressed Venezuelan debt. Sanctions imposed by the U.S. Treasury have ended that game for U.S. investors, but the debt is there waiting for the next buyer. Argentine debt, which now has the backing of the International Monetary Fund, is less risky. Even though the country’s political risk numbers do not inspire confidence, the likelihood is high that the situation will improve by the third and fourth quarters of 2019.

The truly dark scenarios would only be realized through gross political failure. For example, if President Ivan Duque in Colombia cannot hold together a fragile peace with the guerrillas, that country will see a surge in organized crime and violence that will paralyze its economy. In Bolivia, President Evo Morales could bring his country to its knees by bulldozing his way to another term as president, in violation of the constitution. This would precipitate a surge of public displeasure that would be extremely disruptive.

Venezuela is the extreme case, facing political paralysis, a deteriorating petroleum company producing less than 50 percent of its capacity while it is still expected to provide 90 percent of the government’s revenue, and a humanitarian crisis worse than any in the region in the past century. The contraction of the Venezuelan economy distorts all regional indicators.