South Africa’s new leader launches plan to accelerate growth

Following South Africa’s “lost decade” under the chaotic, often controversial leadership of former President Jacob Zuma, his successor faces challenges that are both daunting and delicate. President Ramaphosa needs to restore basic functionality of the South African state while its ruling party is divided between reformers and radicals.

In a nutshell

- The new leader is banking on growth to make South Africa a well-functioning state again

- President Cyril Ramaphosa has impressive credentials; investors and financial markets have welcomed his first decisions

- If the new government’s “New Deal for Jobs, Growth and Transformation” agenda fails to work, radicals are likely to gain power

During the era of Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s fourth president, who ruled from 2009 until his resignation on February 14, 2018, the country descended into a deep economic crisis with major social and political consequences. Cyril Ramaphosa, chosen by the parliament’s National Assembly to replace the controversial veteran of the anti-apartheid fight, is a decade younger and a participant in the same struggle who went on to become a trade union leader and businessman. He is respected for his negotiating skills.

The head of the African National Congress (ANC) and now president of South Africa tasked with making it a functional state again, Mr. Ramaphosa will need to rely a lot on his famed ability to reconcile differences. He presides over a ruling party and a multiethnic society increasingly divided between radicals and reformers.

Forced resignation

His victory over the former president’s ex-wife in the contest for the ANC’s top position signaled an approaching end of the Zuma years in South Africa. At the party conference, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma represented its left wing and stood for a “radical economic transformation” and “continuity” in the country. Cyril Ramaphosa, in contrast, personified the most moderate and liberal factions. His opponents claimed he was an agent of “white” (or, depending on the accuser, “black”) capital.

The ANC has seen much of its legitimacy and popularity melt away.

As the ANC’s new president, Mr. Ramaphosa initiated a delicate process of removing Mr. Zuma from office. The party’s “Top Six,” a group of high-ranking members with significant decision-making power (it includes both Mrs. Zuma and Mr. Ramaphosa), were split over Mr. Zuma’s destiny. In the end, fears prevailed that with the controversial president remaining, the ANC would risk a historic defeat in the 2019 general elections.

Although it remains the country’s leading political party, the ANC has seen much of its legitimacy and popularity melt away during the last decade. President Zuma’s poor performance in the face of South Africa’s economic failings and demographic challenges cost the ANC control over some key constituencies, including in the cities of Johannesburg and Pretoria, and in the municipality of Nelson Mandela Bay, in the 2016 local elections. The embattled President Zuma was forced to resign after the party finally announced its intention to bring forth a motion for a vote of no-confidence in him.

‘Lost Decade’

Once a fighter in the ANC’s armed wing, Jacob Zuma liked to present himself as a man of humble origins and no formal education. In 2009, his popularity and commitment to “radical economic transformation” earned him the support of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) which, together with the ANC, form the Tripartite Alliance – the backbone of the country’s ruling system. The alliance was forged in 1990 to fight the apartheid system. Once elected president, however, Mr. Zuma failed his enthusiastic supporters, as he turned out to be a populist leader marred by corruption scandals.

In 2013, Julius Malema – who had made his name in politics as the firebrand leader of the ANC youth wing – created the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), presenting himself as the only true champion of a renewed fight against colonialism and “white” capitalism, and trying to claim the ANC’s mantle of “radical economic transformation.” In the meantime, the Democratic Alliance (DA), consolidated its position as the main opposition party and an alternative to the ANC.

External factors have contributed to the South African economy’s disappointing performance in recent years. They included a global recession, China’s economic slowdown, a slump in commodities prices and a severe drought that compromised many communities’ water, food and energy security. However, the impact of these factors has been aggravated by calamitous governance.

According to Statistics South Africa, unemployment in 2017 stood a 36.6 percent (including both the unemployed searching for work and discouraged workers). A 2017 research project by the University of Pretoria revealed that eight out of 10 fourth grade pupils could not read at an appropriate level; reading scores have not improved since 2001. The country’s health system is inefficient, and more than 80 percent of the population has no medical insurance. South Africa ranks 71st in the Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (in 2001 it was 38th). And, according to a report by Oxfam (an England-based coalition of organizations focused on alleviating poverty), inequality levels in South Africa today are higher than they were during the apartheid era.

As if these problems were not enough, Mr. Zuma’s presidency was marked by corruption scandals.

The poor performance of the economy and growing inequalities have led to polarization and the racialization of political discourse in South Africa, particularly among the left.

Enter graft

As if these problems were not enough, Mr. Zuma’s presidency was marked by corruption scandals. In 2014, the Public Protector’s office accused the president of spending nearly $250 million in taxpayer money on his rural home in Nkandla, allegedly for “security upgrades.” In 2017, revelations about a role of the wealthy, Indian-born Gupta family members in a reshuffling of Mr. Zuma’s cabinet prompted acrimony that the South African state was captured by a patronage network. These suspicions were augmented by the president’s commitment to a questionable nuclear plant deal with Russia which would cost South Africa more than $73 billion – approximately equal to the country’s annual fiscal revenue.

Another scandal illustrated how pervasive that patronage network, and how fragile the postapartheid South Africa, could have become. In 2016, the British public relations agency Bell Pottinger was hired by the Gupta brothers’ flagship Oakbay Investments company to orchestrate an “economic emancipation” campaign. Based on slogans like “economic apartheid,” “economic emancipation” and “white monopoly capital,” the campaign was allegedly designed to divert the public’s attention from the Zuma-Gupta connections.

Political challenges

President Ramaphosa, the man Nelson Mandela had seen as the best candidate to succeed him, has a CV which lists such roles as activist lawyer, key negotiator of South Africa’s democratic transition, and founder of the biggest and most powerful trade union in the country, the National Union of Mineworkers. As he moved from politics to the economy, Mr. Ramaphosa became a poster child of South Africa’s black economic empowerment program. On the strength of his political accomplishments and negotiating skills, he joined the ranks of South Africa’s most successful – and richest – businesspeople.

His 2018 ascent to the country’s presidency sparked a national wave of optimism. However, the new leader faces stiff political challenges, including uniting the fragmented ANC, redefining the Tripartite Alliance, dealing with opposition parties and addressing the land question.

Mr. Ramaphosa won the party’s leadership position by a narrow vote margin. The former president still has many supporters within the ANC, particularly among those who benefited from his policies. In the short term, his successor has to make sure that the party stands behind him – which normally means avoiding major changes. In the medium term, though, the ANC must try to regain its credibility with the electorate, which entails removing from positions corrupt or incompetent members.

As for the backbone Tripartite Alliance, the president, the COSATU, and the SACP have jointly committed to eradicate the Zuma-era patronage system. Mr. Ramaphosa’s business-friendly political philosophy, though, may start posing a problem for his partners. In a country where low productivity, a rigid labor market, and frequent strikes are often cited as the leading obstacles to growth, maintaining this particular alliance may prove a tall order.

Many political and social groups defend land expriopriation as a necessary step to revert colonial wrongs.

The president’s third challenge will be to consolidate the ANC. The party’s internal and international credibility is linked to the idea of South Africa being an example of a successful democratic transition and reconciliation, anchored in a progressive and solid constitution. However, disappointing growth levels and persisting inequalities pose a threat to the ANC’s legitimacy. The party has seen an erosion of its support base to the benefit to both the DA and the EFF.

Faced with these political risks, President Ramaphosa will also have to ensure that violent street protests, like the ones that recently erupted in the town of Mahikeng, do not compromise his announced goal of attracting $100 billion in new investment over the next five years. Protesters in Mahikeng were demanding jobs, housing and – above all – immediate removal of North West Premier Supra Mahumapelo, an ANC politician implicated in yet another corruption scandal with Mr. Zuma. While such protests undermine stability in the country, they are not aimed against the president. In fact, the scandal gives Mr. Ramaphosa additional leverage to start reforming the ANC.

The land question

Julius Malema’s greatest political victory thus far has been the National Assembly’s adoption of his motion on land expropriation without compensation (EWC). The ANC supported it, too. Land expropriation was one of the hot topics of the December ANC conference and Mr. Ramaphosa accepted this in principle, in an attempt to soften his pro-business image among the ANC’s more radical factions. He has consistently mentioned, however, the need to be cautious about land redistribution ideas and keep in mind other imperatives, including food security. The EWC will now be referred to the National Constitutional Amendment Committee.

The matter has a deep resonance in South Africa. Although the pattern of land ownership has changed a lot since the end of apartheid and the country’s population is increasingly urban, land expropriation remains a potent political issue. Like in neighboring Zimbabwe, many political and social groups defend it as a necessary step to revert colonial wrongs. Some argue that Mr. Ramaphosa may be the best leader to preside over the debate and ensure that potential implementation of a land reform is done without compromising the property rights.

Positive signs

President Ramaphosa’s first political nominations were an unequivocal message of change. Nhlanhla Nene, an experienced public servant and finance minister whose arbitrary firing by Mr. Zuma in 2015 led to turmoil in financial markets, returned to the post. South Africa’s business circles also welcomed the appointment of another respected former head of the finance ministry, Pravin Gordhan, dismissed by Mr. Zuma in 2017 for opposing the nuclear deal, as minister of public enterprises.

Considering the sorry financial shape of some of the country’s state-owned companies, this is also a critically important post. Mr. Gordhan is expected to try to partially privatize firms in this sector, although this will be opposed not only by President Ramaphosa’s political opponents such as EFF but also by some of his allies within the Tripartite Alliance. To help to bridge a gap in the government’s budget (it stands at 4.3 percent of gross domestic product, (GDP), in the 2017/18 fiscal year), the Ramaphosa team has made a daring decision to raise South Africa’s sales tax (VAT) from 14 percent to 15 percent, the first such hike in the postapartheid era.

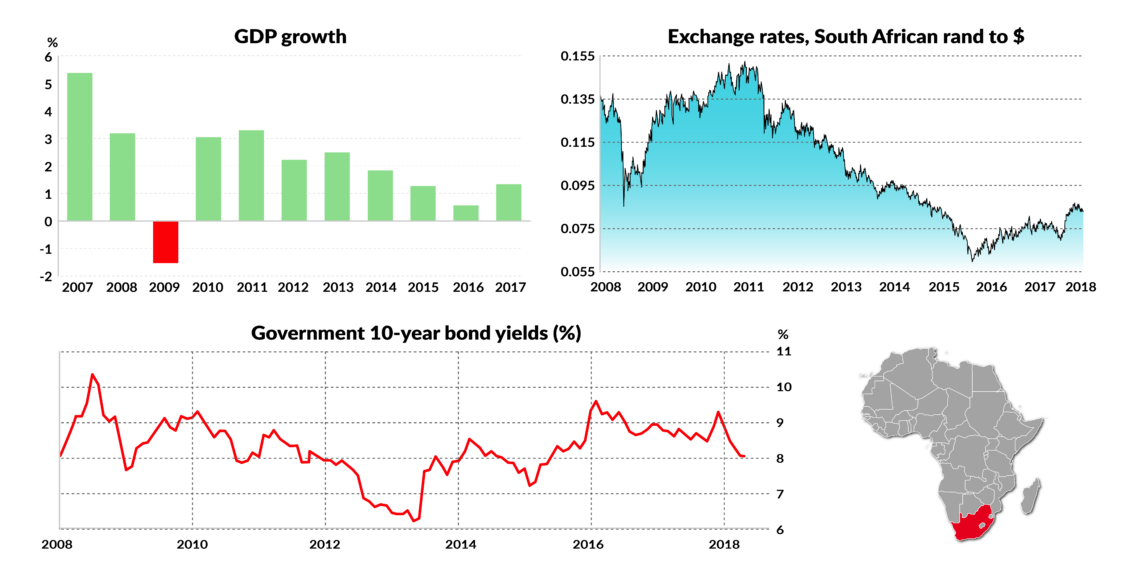

President Ramaphosa’s leadership has already triggered positive market reactions. Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s has doubled its forecast for South Africa’s GDP growth, from 1 percent to 2 percent in 2018, on the basis of renewed confidence among national and international investors. Moody’s, in its turn, refrained from downgrading the country’s debt to junk on the assumption that the country’s institutions would regain strength under more transparent and predictable policies. Also, the International Monetary Fund, in its April 2018 report, raised its growth forecast for South Africa from 0.9 percent in 2018 and 2019, to 1.5 percent and 1.7 percent, respectively.

Scenarios

Following President Zuma’s resignation, the outlook for South Africa’s 2019 general elections has changed. The most likely scenario is that of a comfortable ANC victory.

Some divisive issues remain, the most important of them being the implementation of a national minimum wage system, land expropriation, privatization of state-owned enterprises, and the former president’s corruption charges. They will continue to create tensions within the ruling party and the Tripartite Alliance. However, no major disruptions are expected before the 2019 balloting.

A scenario of a smaller victory, which would force the ANC to seek ruling coalitions with smaller parties remains feasible, though less probable.

After the elections, however, South Africa is very likely to find itself once again at a turning point. Two different scenarios emerge for that period. The factor which will determine the country’s future, in the long run, is the shape of its economy. Continued stagnation will deepen political polarization and spur unrest. An economic recovery, on the other hand, will likely pave the way for political stability.

Under the first scenario, more possible within the context of a comfortable ANC victory, South Africa will peel away from the “Radical Economic Transformation” agenda to embrace Mr. Ramaphosa’s “New Deal for Jobs, Growth and Transformation” project. This new deal calls for – and depends on – a stretch goal of a 3 percent GDP growth in 2018 and 5 percent by 2023. If the government manages to retain the confidence of investors, the project may work. Under this scenario, however, the political Tripartite Alliance will likely break up.

Under the second scenario, political polarization and weak recovery will compromise the new president’s pro-growth agenda. As the initial wave of support and optimism around his ascent to power dissipates, Mr. Ramaphosa will be forced to seek alternative ways to legitimize his rule. He will have little choice but to pursue compromises with the more radical elements both within and outside the ANC. In such circumstances, Mr. Malema of the EFF will press forward with accusations that the president is a stooge for “white capital” and the idea that decolonization is “unfinished business.” His calls for land expropriation and nationalization without compensation of mines and banking could prove effective in the environment of ongoing economic crisis and high youth unemployment.