Malaysia’s king becomes kingmaker

Following a tumultuous power transition, Malaysia finds itself in a political crisis. The power balance in the country stands to be determined by whether political factions turn to the parliament or the constitutional monarchy as a source of ultimate authority.

In a nutshell

- Malaysia's unelected government may have to step down

- The king has stepped in to stabilize the situation

- The current truce may not hold

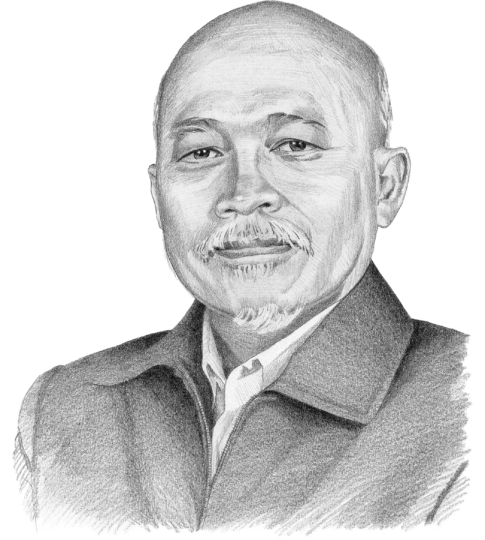

Malaysian politics, already in flux following a power grab in February 2020, has taken an unprecedented twist. On September 23, 2020, the opposition leader, Anwar Ibrahim, attempted to take over the premiership by informing the king that he had amassed a “strong, formidable and convincing majority” of MPs to form a new government. Exactly a month later, on October 23, the prime minister – fearing being deposed amid a worsening Covid-19 pandemic – proposed that the king impose emergency rule.

To everyone’s shock, King Abdullah – a constitutional monarch who enjoys largely ceremonial powers but whose assent is needed for major decisions like invoking emergency powers – rejected the prime minister’s executive plan. The king then urged all political leaders to “stop their politicking” and get down to tackling Covid-19.

The decision brought relief to many Malaysians, who had been kept on edge by the country’s latest political crisis. Had the king consented, parliament would have been suspended and national elections postponed. It would also have delayed the approval of the new government budget, which has taken on some urgency due to the massive funds needed to manage the pandemic. If the parliament were to reject the budget, it would amount to a vote of no confidence and the prime minister would have to step down.

It is a matter of contention whether the king can say no to the prime minister.

This royal display of constitutional independence, especially in rejecting emergency rule, had never happened before. It threw the premier’s ruling coalition – already wobbly because of its razor-thin, two-MP majority – into a tailspin. In an unexpected development, the king has emerged from the political turmoil as a kingmaker.

It is a matter of contention whether the king can say no to the prime minister. But, by refusing to endorse emergency rule so as to save the country from the political gridlock caused by the power struggle, the monarch has forced the competing political elite to rein in their power jostling and focus on tackling the pandemic. There have been proposals of national reconciliation, to which even the Anwar-led opposition responded positively. Mr. Anwar has reached out to the beleaguered prime minister for a bipartisan plan to save the country from the ravages of the public health crisis. But what kind of a deal will emerge from this imbroglio?

Constitutional authority

In rejecting the emergency proposal, the king decreed that there was no need to resort to such extreme measures since the government had so far proven its capability to manage the pandemic.

As an elective monarchy, Malaysia is ruled by a council of hereditary rulers of different states in the federation who elect the head of state from among themselves. Their joint statement shed more light on the monarchy’s decision. The rulers declared that the royal veto had been guided by the principles of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy. They also disclosed their concerns over “the serious implications [that] the emergency proposal would have on the image of the country; investor confidence within and outside the country; as well as on the livelihood of the people.”

Significantly, the rulers stressed the importance of “respecting the check and balance mechanism between the government and the King’s role” and the overarching need for “balancing the various competing demands so as to guarantee justice and contain any abuse of power.” Such references from the monarchs had never been heard publicly before in Malaysian political history. This unprecedented royal posture was widely seen as a slap in the face of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin, whose government had come to power after a political coup.

Reflecting a widespread sentiment, the publication Aliran quoted civil society group Monsoon Malaysia as saying: “The last thing the people want is emergency rule that smacks of authoritarianism, curbs democratic voices and instils fear and resentment among the population.”

Crisis in the making?

The political drama is far from over. Eager not to be seen as disloyal to the king, the country’s various political factions are now locked in a huddle to strike some kind of national reconciliation despite their growing mutual distrust. Prime Minister Muhyiddin, crestfallen after the royal rejection, contemplated resigning but was talked out of it by his coterie of allies. Given his flimsy majority, his immediate task of getting the new budget passed this month will sorely test his political and leadership skills.

The country’s political elite will have to grapple with fundamental questions about the role of the monarchy.

Complicating his position are the many enemies he has made since coleading the February power grab that toppled the previous government, led by Mahathir Mohamad. Mr. Muhyiddin’s unelected administration is still not perceived as fully legitimate, making this month’s budget vote crucial. Not only is there mistrust within his own coalition, the Anwar-led opposition is also ready to bring him down – even if it is currently abiding by the king’s decree. Despite having missed yet again his chance to become prime minister – at least for now – Mr. Anwar could still play a role in future developments.

If by some stroke of fate he does end up as prime minister, it would be a dramatic comeback by one of the most tenacious politicians the country has ever seen. In the 1980s, the firebrand youth leader was co-opted into politics during Dr. Mahathir’s first tenure as prime minister. In 13 years, Mr. Anwar became deputy prime minister – within reach of the most powerful position in the country. This rapid rise has earned him many foes.

But before this scenario can come to pass, the country’s political elite will have to grapple with fundamental questions about the role of the monarchy in the country. Traditionally, the king’s role has always been symbolic. A previous independent-minded king once tried to exercise his authority by withholding assent to parliamentary bills, causing problems to the executive. This led to the country’s first constitutional crisis with the royalty, which was only resolved when the Mahathir government amended the constitution to clip the wings of the monarchy.

The current crisis is of a completely different nature. Here the king is not the destabilizing power, the political elite is. This tussle began in February when an anti-Anwar faction conspired to block his rise to the premiership, in breach of an earlier agreement.

Given the resulting mess, the king then stepped in as savior in his first major intervention. But he is now treading on thin ice as he tries to steer the country toward stability by forcing, through a royal decree, the competing political elites to support the incoming budget. If the MPs go along, it would mean saving the embattled prime minister, who is desperate for a lifeline, through a royal decree.

Malaysians are now wondering whether the king is beginning to overstep his constitutional powers.

Scenarios

Malaysians are now wondering whether the king is beginning to overstep his constitutional powers. In a democracy where elected political leaders are the ultimate lawmakers, can and should parliament be “guided” by royalty? Should the monarch venture into this territory?

One lawyer has already filed a suit asking the court to determine if the king was legally allowed to block the executive’s “advice” to introduce a state of emergency. Does this legal action not amount to suing the king, and can the monarch be sued?

All these questions are fodder for a potential constitutional crisis. Given these new ambiguities, the MPs could decide to reassert their constitutionally-endowed power, vote down the government’s budget to remove the embattled prime minister – just to show that the parliament is where the center of political gravity lies.