Regime change: postelection scenarios in Malaysia

The election of Malaysian Prime Minister Mohamad could make way for a change in politics after throwing out the coalition that had ruled Malaysia since independence. Meanwhile, the opposition is embroiled in a debate over its own identity. Beyond the country’s borders, the government approaches its neighbors, like China and Singapore.

In a nutshell

- Back as prime minister for the second time, Mahathir Mohamad is shaking up Malaysian politics

- The new government will push an ambitious reform agenda, while the opposition is struggling to find a new identity

- Mahathir is already taking a new line in foreign policy, finding common cause with Indonesia and raising concerns with China

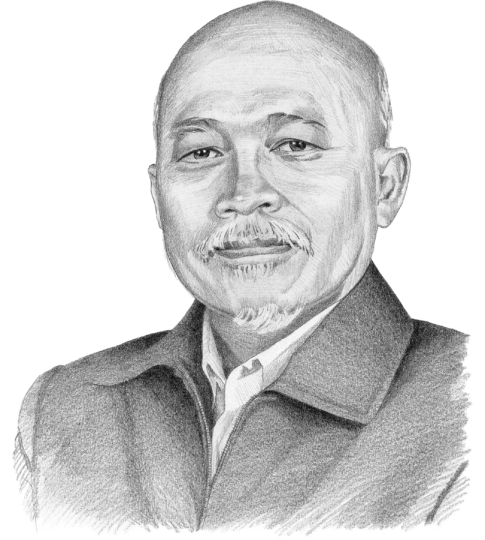

Twenty days after he was elected to the country’s highest office for the second time, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad made an official visit to Indonesia. By the standards of Southeast Asian diplomacy, that was fast. Mr. Mahathir received a red-carpet welcome from Indonesian President Joko Widodo, 40 years his junior and a political neophyte compared to the Malaysian nonagenarian.

During his stay, Mr. Mahathir made a geopolitically significant proposition: Malaysia and Indonesia should join forces to oppose pressure from Europe on the global palm oil industry. As the world’s top producers, the two Southeast Asian economies dominate the palm oil market. “Our palm oil is threatened by Europe and we need to oppose them together,” he said at a joint press conference with Mr. Widodo.

“European countries used to be covered with forests but they’ve cut them down and nobody argues with them about it. But when we clear land they say it pollutes the climate,” Mr. Mahathir complained. Within weeks, the Malaysian and Indonesian foreign ministers met to follow up on a plan to counter the EU’s move to phase out the use of biofuel in transport fuels.

Making history

Fifteen years after stepping down from the job, Prime Minister Mahathir is back with a bang. During his first tenure in the office, from 1981 to 2003, he was known for his combative style of defending his country’s national interests. Now, Southeast Asia and the world will again be hearing more from the outspoken Malaysian leader.

The return of Mr. Mahathir at the age of 92, long past when most leaders decide to call it a day, is almost surreal. It is also catapulting him to the status of a political icon, if not a legend, in Malaysian politics. In so doing, Mr. Mahathir scored many firsts.

The coalition in control since 1957 finally lost power at the hands of the country’s most potent political duo.

No former prime minister had ever come back to dethrone his preferred successor. At the ballot box, Mr. Mahathir threw out the government of former Prime Minister Najib Razak, whom he accused of being a kleptocrat who must be defeated at all costs for the sake of the country. He was determined to remove Mr. Najib, who was widely alleged to be behind the country’s biggest corruption scandal, linked to the state-backed fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB. The dethroning of Mr. Najib also meant that Mr. Mahathir is now the world’s oldest prime minister.

Another first: never before had Malaysia gone through a game-changing “people’s uprising,” and a peaceful regime change at that. This was exactly what Mr. Mahathir triggered when, with his surprising support for the jailed politician Anwar Ibrahim – and with the latter’s equally remarkable backing of the new prime minister – the two leaders patched up their long-standing differences and led the opposition to a stunning electoral victory. The ruling coalition had never lost power since independence in 1957, but it finally did at the hands of the country’s most potent political duo.

In the context of these events that have followed the historic polls of May 9, 2018, there are three possible scenarios going forward.

Scenario 1: A new order?

Over the next several years, if the newly-elected coalition government known as the Pakatan Harapan (PH, Alliance of Hope) lasts at least two terms, we will see a different political order take hold. The people’s rejection of the Barisan Nasional (BN, National Front) regime is a new phenomenon in Malaysian politics.

Increasingly, the emerging narrative is that of a “New Malaysia.” What this New Malaysia is, however, has yet to be defined, and it means different things to different people. The popular view is that the concept is simply the antithesis of the old era; anything that was bad about the old must not be part of New Malaysia. If the old era was exclusivist, for example, “New Malaysia must be inclusive and encourage participation of all parties who wish to contribute towards efforts to rebuild the country,” said Syahredzan Johan, an official in one of the component parties of the PH coalition.

Even Mr. Mahathir himself, who ruled the country for two decades, has called for a break from the past. Weighing in on a debate over financial penalties against the family of the ousted former prime minister, Mr. Mahathir said that “the New Malaysia should even be an improvement on the period during which I was prime minister for 22 years.” The government should “have to go back to democracy and the rule of law and respect the wishes of the people,” he said.

Two challenges face the new government. First is cleaning up the mess of corruption left behind by the Najib administration. Reformism will be the order of the day, possibly leading even to some form of systemic change. Ironically, Mr. Mahathir, who was known as an autocrat, has become the “New Reformer,” embracing Anwar Ibrahim’s battle-tested platform of Reformasi.

Second, Mr. Mahathir and his team will be under pressure to prove that the new government can fulfill the expectations. The inherently disparate alliance must try to put their previous divisions behind them and remain united.

Scenario 2: Existential crisis

All of that said, the regime that the PH alliance overthrew is not to be trifled with. At the core of the dethroned BN coalition is the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the linchpin party that had been in power since the country’s independence in 1957. Once thought to be invincible, BN disintegrated as soon as it lost control. Several partners deserted it, leaving only three original component parties, the core of which is UMNO.

UMNO is itself facing an existential crisis. It is under threat of being deregistered for failing to hold internal party elections, in breach of political regulations. Should this happen, the political impact will be far-reaching, as the party symbolizes the aspirations of the majority ethnic group.

Politics will move away from primordial attachments toward a common center, with greater acceptance and tolerance.

In this battle for survival, UMNO is going through an internal debate over direction and its own identity, giving rise to two contending groups. One of them comprises the old guard that wants to defend the original mission of UMNO as a party for the majority Malay and indigenous communities. The other group rallies a younger, more reform-minded generation that wants to open up the party to all groups, regardless of ethnicity or identity.

The tussle between these two factions was eventually settled when the old guard won and dominated the most recent party elections, throwing the reform-minded members on the defensive, but not necessarily out of action. The future of UMNO now depends very much on how far the younger generation will succeed in the effort to take over the leadership and chart a new course. Nevertheless, the introspective search for another identity for UMNO is unprecedented, reflecting the new terrain that the country has entered.

The course taken by UMNO will partly be influenced, if not defined, by the broader political landscape now dominated by the leadership combination of Mr. Mahathir and Mr. Anwar. Collectively, the dynamic duo has come to symbolize a political ethos around “post-identity.” Malaysian politics will increasingly move away from primordial attachments toward a common center, where greater acceptance and tolerance of each other will be the new norm. This may happen without changing the traditional characteristic of Malaysia as a Malay-dominant polity that remains pluralistic, with Malay and Muslim aspirations as the stabilizing center.

Scenario 3: Beyond the border

The political shifts do not stop at Malaysia’s border. As one of the most developed economies in Southeast Asia, the country’s political dynamics –especially those that affect its stability and security – will be of importance to its neighbors in the region and beyond.

Nothing can underscore this better than Prime Minister Mahathir’s wooing of Indonesian President Joko Widodo for a partnership over European pressures on the palm oil industry. With neighboring Singapore, Mr. Mahathir also created some ripples when he threw into doubt a joint high-speed rail project signed by the Najib government. He also suggested renegotiating the long-standing supply of water from Malaysia, a strategic resource to Singapore.

Mr. Mahathir’s biggest challenge is further afield, in Beijing. China is at the heart of some financially troubling megaprojects initiated by the Najib government. The new prime minister has taken issue with the Asian giant for financing these projects, which were placed under investigation in Kuala Lumpur following the defeat of the previous regime.

At issue is a Chinese model that emphasizes loans over investments and deadlines rather than deliveries.

Underscoring his seriousness, Mr. Mahathir himself traveled to Beijing in August for a five-day visit to discuss with Chinese leaders the China-funded projects in Malaysia. He wants to renegotiate many of them, as part of a larger goal of cutting down on the massive national debt inherited from the previous government. Dispatched in advance to China was the prime minister’s trusted aide, Daim Zainuddin, who carried a letter to the Chinese leadership. His task was to pave the way for the top leaders’ talks. At around the same time, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Kuala Lumpur. Mr. Mahathir has already frozen more than $24 billion-worth of China-funded infrastructure projects linked to 1MDB.

At the end of his trip, Mr. Mahathir announced at a press conference in Beijing that Malaysia would now cancel the frozen projects, in a decision he said Chinese leaders had “agreed” on. “We do not want a situation where there is a new version of colonialism,” said the Malaysian leader after his meeting with Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang.

More than the particular projects, what is at issue is the Chinese model for economic collaboration. One aspect of that is Beijing’s preference for extending loans with high interest rates rather than investing directly in the projects, and for payments based on timelines rather than project deliveries.

Another is the Chinese propensity to use their resources, workforce and expertise for the projects they are involved in, instead of relying on local firms and creating jobs domestically. This Chinese model has also been questioned in several countries in Asia and Africa for the problems and social tension they generate.

Mr. Mahathir, however, is striking a careful balance in his approach to the problem of the mountain of debt left behind by his predecessor. Preserving good relations with a rising economic superpower that is a significant market for Malaysian products is also on the prime minister’s agenda. “We do not blame the Chinese government because their companies signed an agreement or several agreements with Malaysian companies under the auspices of the government of the day,” Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah said in a July interview with Singapore’s Straits Times. “So you can’t fault the Chinese government for that.”

The political earthquake in Malaysia is also creating reverberations globally. Before he finally calls it a day (again), Mr. Mahathir is likely to make more waves as he brings his assertive persona to the international stage.