Mali’s two wars

Mali is waging war against terrorists based in the north of the country. But Bamako is also conducting a political campaign against ethnic populations who want more autonomy. Though France’s involvement has kept the Malian government stable, increasingly, officials are asking why it should continue.

In a nutshell

- Mali faces huge problems, including violence and poverty

- Terrorist groups have allied with northern ethnic groups who want autonomy

- International troops, led by France, help keep the Bamako government in power

- As Bamako antagonizes northern populations, France questions its commitment

Mali’s presidential election, held this past July, is unlikely to improve the country’s lot. Instead, the reelection of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, known as IBK, and the legislative elections scheduled for October 28, will surely add further pressure to Mali’s fractured society. But the country has some urgent challenges that must be addressed, including poverty (Mali is the 17th poorest country in the world), systemic corruption, human trafficking and, above all, the ever-growing cleft between its north and the south. France, which has a military presence in the country and is stabilizing the regime at arm’s length, is trapped in a situation of increasing hopelessness.

In June, just over a month before the presidential election, French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian explained that the Algiers agreement – an accord signed between rebel forces in the north of the country and the government in the capital, Bamako – “contains everything needed to restore peace in Mali and in the entire Sahel region.” Less diplomatically, he added: “The political will to make the agreement a reality is still needed. … I hope that it will be [there] after the presidential election.”

Indeed, more than five years after the military operation to counter the rapid rise of armed groups in the country, nothing has been resolved in this enormous, fragile and composite country of 1.2 million square kilometers. While this half-decade has brought no convincing political results, it has revealed the growing divergence of objectives between Paris (as well as the international community as a whole) and Bamako.

Paris ‘saves’ Bamako

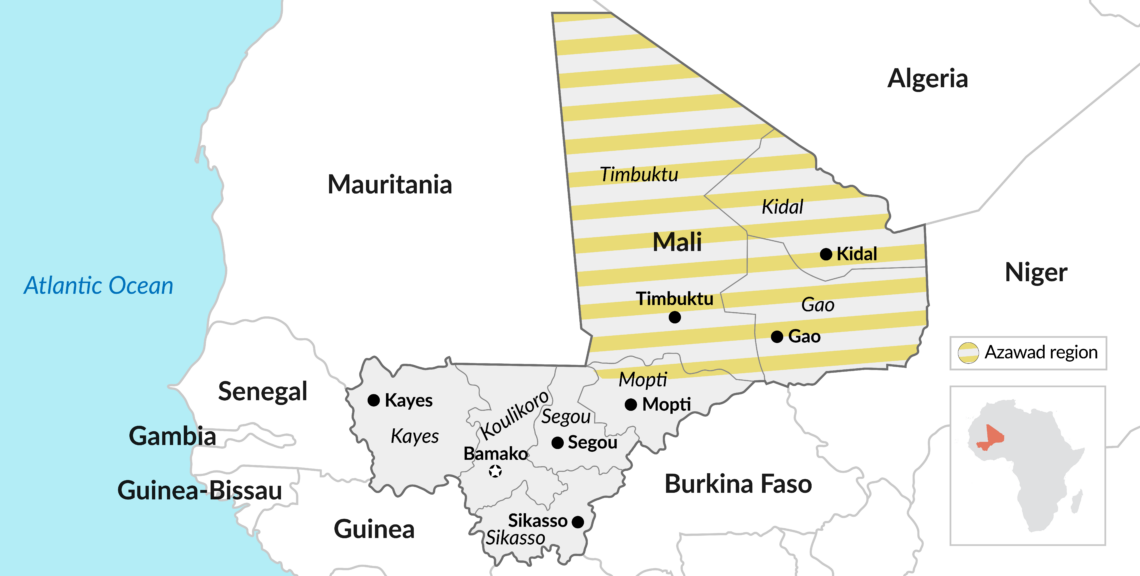

In January 2013, France intervened to “save” Bamako from various armed groups. At the head of these groups was the Salafist movement Ansar Dine (allies of convenience with the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, MNLA). The groups came from the Azawad region, in the country’s northern Sahel, which includes the administrative regions of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. The 3,500 man-strong Operation Serval halted their progress and pushed them back to the north.

Paris is asking Bamako to start the political process set out in the 2015 Algiers agreement.

The initiative was renamed Operation Barkhane in August 2014, following the integration of forces from neighboring countries. France’s goal was to eliminate the jihadist groups and disperse them as much as possible, weakening their presence throughout the vast Azawad territory, while at the same time securing the border with Niger to stop the flow of men and arms, especially those coming from Libya. There are still 1,600 French soldiers in Mali today, and more than 4,000 active throughout the Sahel region (in Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad). On a tactical level, they conduct intermittent, targeted strikes on groups, convoys or jihadist sites.

The sheer size of the region makes it impossible to control entirely. This is why Paris is asking Bamako to take over and deploy its army but also, crucially, to start the political process set out in the 2015 Algiers agreement.

The ‘Tuareg problem’

The issue still plaguing Mali is the historic mistrust between the Tuaregs of the north and the Bambara of the south. If France has been carrying out a “war on terror” for the past five years, then Bamako has been waging a political, economic and social war against the demands for autonomy by groups in the north – not only the Tuaregs but also the Fula. A key problem for Mali is that very diverse populations, both ethnically and culturally, inhabit the country. The Tuaregs, who are nomadic Berbers, do not feel that they have anything in common with the people of the south.

Historically, the Tuaregs, or the “blue people” (the indigo-dyed clothes they wear often stains their skin), also known as the “people of infinite space,” have always lived in the vast desert areas of the Sahel. Borders, often artificial and drawn up during decolonization, mean nothing to them. They trade and lead their herds across frontiers without a second thought. Times have changed, of course, and the Tuareg population is being gradually diluted by black farmers and Fula nomads – but the group still preserves its unique character. The “Tuareg problem” remains and has been waiting for a solution since Mali’s independence in 1960.

Between 1960 and 2010, there were four conflicts between Bamako and the northern regions: in 1963-1964 (with major massacres of civilian populations), in 1990-1996, in 2006 and in 2007-2009. These are conflicts that have created very serious disputes between the two parties – decades during which the Malian state has neglected the development of the north.

Algiers agreement

It was against this backdrop that a fifth conflict erupted in January 2012, when the Malian Army faced off against the Tuareg rebels of the MNLA and Ansar Dine (allied to other Islamist movements). The MNLA demanded self-determination and the independence of the Azawad region, which the Malian government refused in the name of territorial integrity. Alongside its military intervention in 2013, France strongly pushed the parties to negotiate. This led to the 2015 Algiers agreement, to which Foreign Minister Le Drian has reiterated his commitment.

The agreement underlines Mali’s territorial integrity and bars any chance of greater autonomy for the northern regions.

The agreement has not produced significant results, which comes as no surprise: it underlines Mali’s territorial integrity and bars any chance of greater autonomy for the northern regions, only recognizing Azawad’s unique status in vague terms. Moreover, the Algiers accord did not build on the 1992 and 2006 agreements which, had already allowed for the creation of regional assemblies and responsibility for a share of security at the local level.

Between a rock and a hard place

France and the international community are thus faced with an impasse. The international military forces in Mali are in an impossible situation, unable to act in an ethno-regional conflict of a scope beyond their ability to manage. They continue their intermittent “cleanup” operations against jihadist targets, but lack the structural and long-term means to counteract the root causes of the issue: Tuareg irredentism, which now includes Islamist terrorism.

The French military presence is therefore becoming increasingly meaningless, given that the government that it is trying to support is pursuing objectives which are divergent or even contradictory from French ones. Why is France staying in Mali? What are the aims of its mission today? What is France’s agenda in the medium term? These questions, being asked by more and more generals, are embarrassing French politicians who clearly do not want to pressure IBK into finally respecting the Algiers agreement.

Intelligent federalism

There is a potential solution to the problem. In a country of such diverse populations, clouded by age-old mutual mistrust, the hierarchical centralism inherited from the French colonial administration is doomed to fail. Only an intelligent federalism adapted to local conditions could reinvigorate the stalled peace process.

The solution to Mali’s problem is therefore institutional. Paris, however, embarrassed by its colonial past and fearing accusations of interference, does not dare to push such an agenda. Bamako, meanwhile, sees no reason to embark on a path that would lead to a weakening of its power.

It is also true that Mali is facing difficulties of such a magnitude that make it wary of taking on such a project. The ethnic tensions that arose in early 2018 in the center of the country – in which the Dogons (a sedentary people) accused the Fula (nomads) of links with terrorist groups – further complicate the problem.

Still, while the institutional question may be taboo in Mali, it is also unavoidable.