Moldova’s future is tied to Russia’s war in Ukraine

The tiny nation between Romania and Ukraine wants to join the European Union and regain control of its Kremlin-backed Transnistria region. Kyiv’s triumph could advance both aims.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s war in Ukraine offers Moldova new risks and opportunities

- The fate of the breakaway Kremlin-backed Transnistria region is in play

- Moscow’s success in war could halt Moldova’s Western integration

In June, amid the war in Ukraine, the European Union offered Moldova candidate status for membership in the 27-nation bloc. This was a big step with a hazy outlook. The former Soviet republic had long been kept off the list of applicants for good reasons, including endemic corruption and a frozen conflict in its Transnistria region.

The obstacle of corruption could have been overcome, much as similar concerns were overlooked when Bulgaria and Romania were admitted to the EU. But the frozen conflict – involving the long-standing presence of Russian troops – is a different matter. The decision to grant Moldova candidate status came as part of the same offer to Ukraine, which in turn was an attempt to provide security guarantees without a military component. The moral support in giving these two nations the prospect of joining the EU is important. But the move does take the question of enlargement into uncharted waters.

NATO has a general rule against accepting new members that have foreign military bases on their territory. If Brussels is now intent on opening negotiations with Kyiv and Chisinau on membership, it will have to factor in the possibility that both countries will have Russian troops on their territories, perhaps for the foreseeable future. Moldova, with less than 3 million people, encapsulates this problem in a more manageable size and location than Ukraine, with more than 40 million people.

The Soviet Union annexed the present-day territory of Moldova from Romania in 1940 and then constituted it as the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. When the USSR broke up, it followed the other 14 Soviet republics in proclaiming independence. That provoked an armed conflict with the Russian-speaking population in the eastern part of the country and Moscow’s intervention on their side.

Maintaining frozen conflicts constitutes an important tool of Russian foreign and security policy.

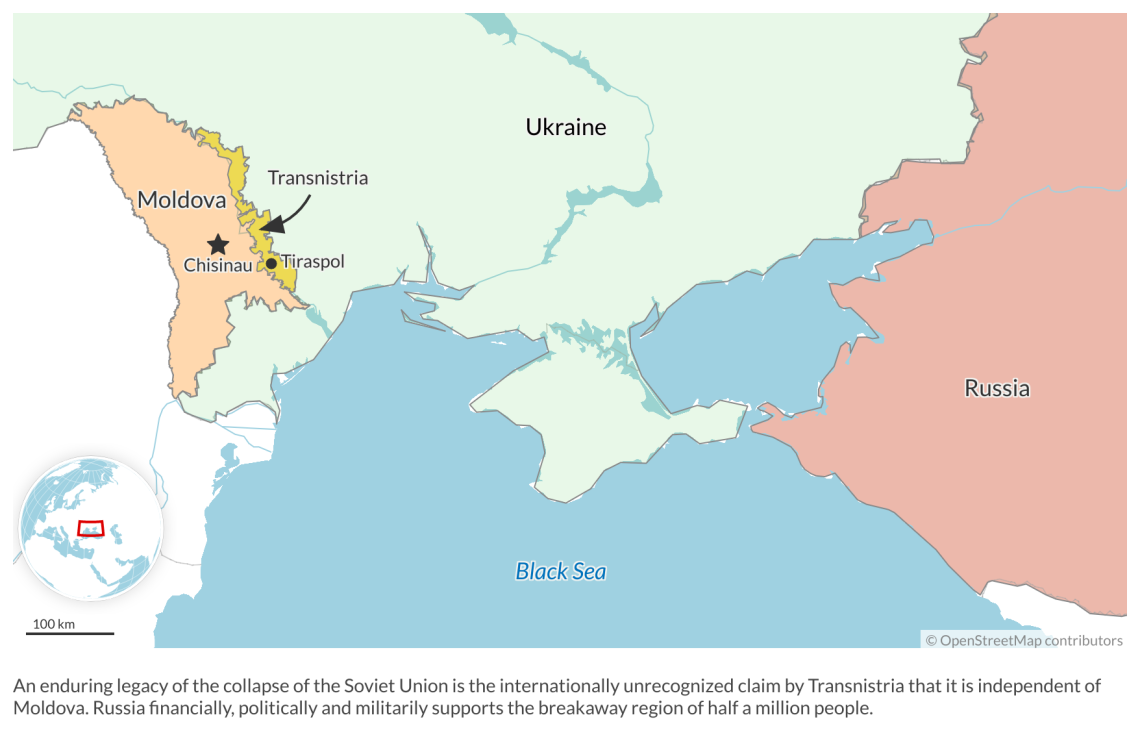

Controlling a tiny sliver of land along the east bank of the Dniester River bordering Ukraine, the rebel leadership announced the formation of the independent state of Transnistria and appealed to the remaining Soviet garrison for protection against Moldovan government forces. A military stalemate was quickly achieved, leaving the “government” in Tiraspol in charge of their “republic.” Three decades later, the political divide remains unresolved over the territory with half a million people.

Moldova wants the Russian troops removed and, like most of the world, does not recognize Transnistria’s independence, while the region’s “foreign minister” said joining the Russian Federation remains the goal.

See also by Stefan Hedlund

Nonrecognition and trouble in international relations

The Kremlin’s frozen conflicts

Maintaining frozen conflicts is an important tool of Russian foreign and security policy. Transnistria is not alone. Other examples range from Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan to the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, seized by Russia in its 2008 war, and the eastern Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine, captured during Russia’s 2014 military invasion.

The common denominator is that Russia intervenes in a conflict where it claims its “compatriots” are being maltreated. Instead of pressing for a military solution and outright annexation, as in the exceptional case of Crimea in 2014, the common practice has been to promote the formation of unrecognized state-like formations under its control.

There are two upsides for the Kremlin. One is leverage over governments in internationally recognized states that refuse to play the Kremlin’s game. And a second, much greater benefit comes from the existence of territories that are outside the control or legitimate law enforcement institutions.

Where crime and corruption flourish

The Republic of Chechnya is an example. It is run as a personal fiefdom by Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov. Territories such as these serve as incubators for organized crime and corruption. Given the high-level corruption that links Russian officialdom with Russian organized crime, the benefit of having access to such territories is obvious. Abkhazia and South Ossetia have played important roles as conduits for covert Russian finance of Ukraine’s Luhansk and Donetsk regions, while Transnistria has provided an important link to Russian-controlled criminal networks in Hungary and Austria.

Facts & figures

Fear of Russia evaporates

What is currently at stake for Russia goes beyond the battle for Ukraine. Irrespective of how that war ends, Moscow’s conduct has already had serious consequences. It has resulted in pariah status for Russia across much of the Western world, in humiliation for its armed forces, and in the degraded capability of its military-industrial complex. And as the fear of Russia evaporates, other countries see opportunities.

The Kremlin’s decision to purchase weapons and ammunition from North Korea proves that the “unlimited friendship” between Russia and China did not extend beyond Beijing pouncing on the opportunity to stock up on cheap Russian oil and natural gas.

Russia’s long-standing role as hegemon in Central Asia is being visibly eroded, as even its staunchest ally Kazakhstan is turning a cold shoulder. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev caused a sensation when he used a public appearance with President Vladimir Putin in St. Petersburg to declare he had no intention to recognize any Russia-sponsored “quasi-state formations” in Ukraine.

The frozen conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh was resolved by force in 2020 when Turkey provided military support for Azerbaijan to recapture much of the territory that had been occupied by Armenia since the early 1990s. Russian peacekeepers have since been forced to abandon their Armenian ally, and Azerbaijan rules the roost.

Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova

This leaves three conflicts.

One is in Georgia, where Abkhazia and South Ossetia have been protected by Russian forces ever since they proclaimed independence. As much of the Russian military has been sent to Ukraine, they are now low-hanging fruit, up for grabs if Tbilisi wishes to make a move.

The second is in Ukraine, where the Kremlin has lost all prospect of realizing its even scaled-back objective of fully conquering the eastern Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts. Its best remaining option may be to settle for a refreezing of the conflict as it was before 2022 – or face a total rout.

The third is in Moldova, where the conflict in Transnistria remains frozen. The reason why Russia wants to keep the status quo is simple to see. Having a foothold inside Moldova is imperative to projecting force to the border of NATO member Romania. Losing that foothold would be a major strategic setback.

At the time of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, there was concern that the Russian armed forces would roll across southern Ukraine and link up with the garrison in Transnistria. Given that Russia did not have sufficient troops mobilized, that was a far-fetched scenario. Yet, after seven months of fighting, Russia has been able to seize nearly 20 percent of Ukrainian territory – up from 7 percent taken in 2014. But its grand territorial aims have largely been frustrated and even rolled back with Ukrainian counterattacks in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Kherson.

The plan for southern Ukraine was to invade in two stages. The first stage had ground forces pushing west to capture key southeastern cities along the M-14 highway – Mariupol, Melitopol, Berdyansk and Kherson. That offensive was supported by forces pushing north from Crimea. Russia currently has a shaky hold on those cities.

Having captured the coastline along the Sea of Azov to just beyond Crimea, the second stage would have been for ground forces to make a further push toward Odesa, where they would be joined by marine infantry from Crimea making an amphibious landing. Once the prize of Odesa – the Black Sea port city with 1 million people – had been conquered, it would have been a walk in the park for Russia to link up with its garrison in Transnistria. The operation failed. Ground forces did not get much beyond Kherson and the planned amphibious landing since part of the aim to seize Odesa was deterred by advanced anti-ship missiles.

If Ukraine can regain its occupied territory from Russia in this war, Moldova will be safer from Kremlin aggression.

If it had been successful in Odesa, the Kremlin would have achieved two major objectives. One is that the entire north shore of the Black Sea would have been a Russian coastline, creating a stranglehold over the ports that are vital to Ukraine’s economy. The second is that the entirety of Moldova would have been placed under effective Russian control. Not being a member of NATO, it would have stood no chance of resisting Russian demands.

These events leave major questions over the outlook for Moldova and its Russian-controlled Transnistria region.

Scenarios

Security dimension

If Ukraine can regain its occupied territory from Russia in this war, Moldova will be safer from Kremlin aggression. Ideally, Kyiv seeks to regain full control of all of its internationally recognized territory, including Crimea and the eastern Donbas regions.

But even Ukraine’s ability to recapture some of the territories that the Russians took this year, coupled with the substantial degradation of Moscow’s military capabilities, has the potential to transform the situation in Moldova.

If a Russian military push is unlikely in the foreseeable future, the Kremlin-supported regime in Transnistria would have a strong incentive to come to terms with the legal authorities in Moldova. Being deprived of economic relations with Russia, the criminal and corrupt elites of Tiraspol would need to show greater transparency and accountability with Chisinau to survive.

Any such agreement would inevitably entail eviction of the Russian military garrison, with an estimated 1,500 soldiers, including local Transnistrians. A withdrawal would end any Russian hopes of retaining a military foothold west of Ukraine. In military terms, Moldova would become integrated with Ukraine and Romania into what may emerge as a new NATO neighborhood.

Political dimension

Assuming improvement in the security situation, the EU would have to confront the nonmilitary reasons why Moldova had not been offered candidate status before the war in Ukraine. Moldova is so small that the EU would have little problem absorbing it. But the challenge will be in overcoming the legacies of corrupt governance.

Bad outcome

A stalemate in the hostilities in Ukraine could happen if the warring sides exhaust each other: Russia would not have the strength to make further territorial gains and Ukraine would be unable to liberate its territory. For the Kremlin, an inconclusive struggle would be a victory, and negotiations for peace would likely entail the easing of Western sanctions. For Moldova, Russian troops would likely be able to stay put in Transnistria, keeping the conflict frozen into its fourth decade.

Prospects for integration of Moldova into the EU would worsen considerably. If Transnistria remains an incubator of corruption and organized crime, it will also remain integrated into Russian criminal networks and their offshoots in Hungary and Austria. This will inevitably have a corrosive influence on those institutions in Moldova that need to be brought up to EU standards.

Recent developments on the ground are hopeful for Ukraine. Kyiv says it has seized 6,000 square kilometers of its territory from Russian control this year, yet almost 120,000 square kilometers out of Ukraine’s 603,700 square kilometers – roughly 20 percent – are still in Kremlin hands.

The game is far from over.