Nigeria’s cautious leader faces hard choices

The first-term record of the reelected president of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari, was mixed, at best. He made modest progress in curbing corruption and the activities of the Boko Haram terror group, but his statist approach to the ruling has not been helpful in Nigeria.

In a nutshell

- Nigeria’s economic potential remains hostage to structural problems and growth-constraining policies

- President Buhari’s statist inclinations have manifested themselves in also in hostility to investors

- His reelection in February 2019 is not expected to mark the beginning of a new era in Nigeria

In February 2019, Muhammadu Buhari was reelected President of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, rich in natural resources, but socially challenged and underperforming economically. While the balance of his first term in office is far from great, the 76-year-old Mr. Buhari managed to deliver limited results on the two key issues of his 2015 campaign: corruption and security.

On the corruption front, a national anti-corruption strategy was implemented; special anti-corruption courts were created; high profile politicians were prosecuted; and stolen assets recovered. However, the problem of grand and petty graft persists in Nigeria, and accusations of politicization have marred Mr. Buhari’s war on it. On the security front, while the operational capacity of the notorious jihadist terror organization Boko Haram has decreased, new threats have emerged.

Rough start

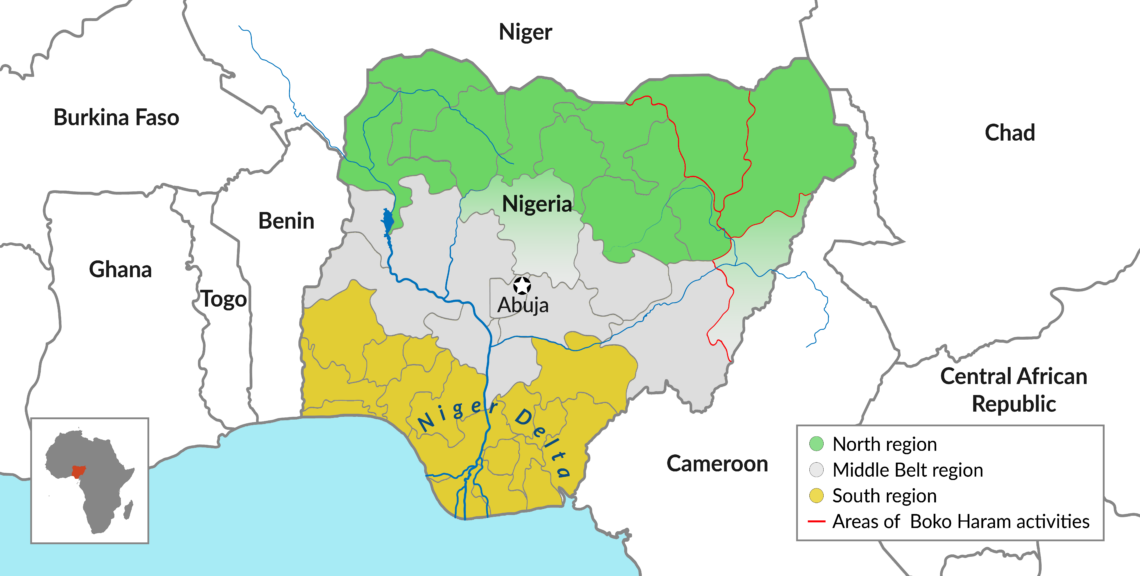

In the country’s North, a split within Boko Haram has led to the emergence of the Islamic State-West Africa (ISIS-WA), which may aggravate the security challenge in the medium to long term. In the Middle Belt region, violence between occupational and religious groups (predominantly Christian farmers and mainly Muslim herders) has escalated into a conflict that claimed more than 2,000 lives in 2018.

Mr. Buhari’s record on the economic front is also mixed. Extremely adverse conditions marked the beginning of his first term. In 2016, for the first time in 25 years, the country’s economy contracted by 1.5 percent – the combined effect of a severe currency shortage, the collapse in oil prices, the declining capacity utilization of Nigeria’s refineries and rising insecurity in the oil-producing Niger Delta. President Buhari’s tack in this hard situation was a strange combination of inertia and statist measures. To his credit, though, the government has also taken some sensible initiatives. Legislation called the Secured Transactions in Movable Assets Act was enacted to foster growth in the private sectorand the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (2017-2020), a development strategy based on diversification, job creation and macroeconomic stability, was launched.

Some economic indicators improved. The services sector registered growth in retail and wholesale trade, telecommunications, banking and motion pictures. The external ratio of debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio improved.

According to the World Poverty Clock, Nigeria has overtaken India as the world leader in extreme poverty.

Overall, however, Nigeria’s economic potential remained hostage to structural problems, growth-constraining policies and negative signals coming from the top of the power structure. President Buhari’s statist inclinations manifested themselves in hostility to investors (according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD),Ghana overtook Nigeria as West Africa’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment in 2018), as well as in protectionist measures, the imposition of currency and capital controls, and the refusal to remove budget-busting fuel subsidies. According to Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics, unemployment soared from 10.4 percent in 2016to 23.8 percent in 2018. By the third quarter of 2018, the combined unemployment and underemployment rate was estimated at 43.3 percent. According to data from the World Poverty Clock, Nigeria has overtaken India as the world leader in extreme poverty. About half of the Nigerian population, or 87 million people, live on less than $1.90 a day.

Challenges ahead

Despite this depressing picture, Mr. Buhari managed to get reelected, defeating Atiku Abubakar from the People’s Democratic Party by a margin of around 4 million votes. Interestingly, in these elections – and contrarily to what has been prevalent in Nigerian politics – divisions were not over ethnic, religious and regional cleavages: Messrs. Buhari and Abubakar are both Muslims from the Fulani ethnic group in the north. The contest this time was all about political orientations and moral qualities. Mr. Abubakar is a successful businessman (though allegations of corruption mar his accomplishments) who defended privatizations and called for a drastic reduction in the corporate income tax rate. Not surprisingly, he managed to win in the more affluent southern states.

Facts & figures

Nigeria's predominantly Muslim North and Christian South

The incumbent’s victory was due to a combination of factors: a record low turnout (35.6 percent) especially in the southern regions, and Mr. Abubakar’s implication in a series of corruption cases. Mr. Buhari’s second term, however, will be defined by how effectively he tackles the country’s substantial economic and security challenges.

To succeed on the economic front, President Buhari would need to change his policy philosophy. Markets do not seem to trust him: on the news of his reelection, the Nigerian stock market lost 85 billion nairas ($238 million), with the benchmark index falling 0.7 percent. The economy, however, is in recovery mode now and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently revised its growth projection upward to 2.1 percent. In any case, the context of excessive regulation, high unemployment, widespread poverty and strong unions remains in place. The protectionist reflexes of the ruling class and pressure from unionized labor seem to be the main reasons behind Nigeria’s reluctance to sign the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement (ACFTA).

A crucial issue facing President Buhari is fuel subsidies, which the IMF is demanding to be phased out.

In November 2018, the Nigerian Labour Congress managed to secure a 67 percent increase in the national minimum salary (to $83 per month), which is to be applied both in the public and private sectors (excluding businesses with less than 25 employees). This may not be sufficient to assure social peace, as both laborers and employers face massive retrenchments and deteriorating living conditions. A crucial issue facing President Buhari in his second term is fuel subsidies, which the IMF is demanding to be phased out. Officially, there is talk of gradually removing the subsidies, but, so far, no immediate plan to do it. In 2019, the cost of fuel subsidies is expected to reach 305 billion nairas (about $1 billion), according to the state budget.

Evolving security landscape

As for internal security, President Muhammadu Buhari faces two grave challenges. The first one is a rise in communal violence between farmers and herdsmen in Nigeria’s Middle Belt region. While tensions between these groups over access to land and water are not a new phenomenon, violence has escalated in recent years, for several reasons. Among them, environmental degradation and insecurity in the north (which pushed nomadic herdsmen further south), the failure of security forces and the justice system to prevent clashes and punish attackers, and the impact of new legislation banning open grazing in some states. Similarly to what happened in the North, local populations are reacting to government inaction by creating their own militias, backed by local leaders. Religious cleavages are now becoming more relevant, as predominantly Catholic farmers fear the increasing presence of Muslim herdsmen in a region where land and water are increasingly scarce resources.

The second challenge for the reelected president is the emergence of new security threats in the northeastern states. Since 2013, the Boko Haram insurgency has claimed tens of thousands of victims and triggered a huge humanitarian crisis, with 1.9 million displaced people and 4.5 million in need of food assistance. The operational capacity and lethality of Boko Haram has been decreasing since 2015, reflecting not only the efficiency of the counterinsurgency operations led by the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) but also the group’s inherent fragilities and contradictions. Still, according to the 2018 Global Terrorism Index, Nigeria remains the third most terrorized country in the world, after Afghanistan and Iraq.

There are reliable indicators, however, that new – and potentially even more severe – threats are emerging. In 2016, Boko Haram split into two distinct factions: Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’Awati Wal-Jihad led by Abubakar Shekau (commonly referred to as Boko Haram) and the Islamic State-West Africa (ISIS-WA) under the command of Abu Musab al-Barnawi, and supported by the Islamic State. Besides the competition for power within Boko Haram, the two men also diverged on fundamental strategic options.

The reelection of Mr. Buhari is not expected to mark the beginning of a new era in Nigeria.

Abubakar Shekau alienated many local populations by conducting attacks against both military and civilian targets, including Muslims. The strategy triggered resistance from the local communities, with many young men joining anti-Boko Haram militias (the so-called Civilian Joint Task Force). In this context, Boko Haram was seen as a brutal force which exerted a predatory power over the populations under its control, and consequently, its attractiveness and recruitment potential were drastically reduced. Abu Barnawi, in turn, wants attacks to be directed against military targets.

Nigeria is a giant with feet of clay. A country with immense potential, but also with high risks and very different prospects. It stretches from Lagos – its affluent commercial capital – to the ethnically and religiously diverse states of the Middle Belt, to the impoverished north. While the reelection of Mr. Buhari is not expected to mark the beginning of a new era in Nigeria, possible scenarios emerge.

Scenarios

Business as usual

Under this first and most likely scenario, President Buhari will readjust some of his policies but abstain from significant reforms, which means the country will continue on its trajectory of economic underperformance. Two indicators for this scenario are the retention of the fuel subsidies and the indefinite delay of the ACFTA (after Gambia’s ratification, the pact has reached its 22-member threshold and the free trade area will begin to function). While such decisions as the recent minimum salary increase and the presence of fuel subsidies (gasoline costs Nigerians less than $0.48 per liter) may buy the government some period of social stability, this scenario is expected to have a negative long-term impact on the country’s stability and security. Nigeria’s economy will continue to be outpaced by population growth, leading to further increases in poverty. With a population estimated at some 203 million and an annual demographic growth of 2.7 percent (between 2010 and 2015), Nigeria is expected to exceed the 300-million-people mark by 2050, becoming the third-most populous country in the world.

According to the 2018 Global Hunger Index, Nigeria ranks 103rd out of 119 countries and the proportion of undernourished has been rising since 2010. Within this context, economic underperformance will lead to a deterioration of security, as deprivation is expected to reinforce the tensions in the Middle Belt and increase the recruitment potential of terrorist groups like ISIS-WA. A rising poverty and popular contestation in the South’s urban centers combined with higher insecurity in the Middle Belt and the North would test the strength of the Nigerian state to its limits.

Economy first

This is a less likely scenario, as meaningful changes in policy orientation usually require changes in leadership. In Nigeria’s case, President Buhari would need to follow the example of some other African leaders and renounce the statist approach to the economy, adopt investor-friendly policies in key sectors (including energy, banking and technology), and allow the market to determine prices, drive growth and create jobs. Among poor societies, however, free-market policies are a hard sell.

In this context, the Nigerian market has a huge potential, due to its size: energetic, positive signals from the government would most likely help to attract significant FDI. Such a government policy inevitably would bring significant risk of social stability in the short and medium term. The removal of fuel subsidies, for example, would trigger strong popular resistance, resembling the 2012 Occupy Nigeria protests.

Even under the most favorable scenario of economic reforms and liberalization, any process of starting an economic renaissancein Nigeria promises to be slow and uneven.