How North Korea’s neighbors are quietly stepping up

The threat posed to international security by North Korea’s nuclear posturing will not be resolved in a flashy manner – neither by an American military strike at Pyongyang’s arsenal nor by Chinese economic pressure on its rogue ally.

In a nutshell

- The North Korean leadership treats its nuclear weapons as the ultimate guarantee of regime survival

- Beijing worries that accepting North Korea as a nuclear state will trigger a dangerous regional arms race

- Notwithstanding the bellicose language coming from Washington, the key to defusing the crisis is in China’s hands

In his presently overused metaphor, Winston Churchill famously described Russia as “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” adding: “but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” This description fits North Korea quite well, too. Of course, for “national interest” one needs to substitute the interest of the Kim dynasty. In recent times, the world again has witnessed sudden twists and turns in Pyongyang’s international posture. One thing, however, seems never to change: the nearly total impenetrability of the world’s most secretive country.

The difficulty in trying to understand what makes North Korea tick stems not only from the isolation of the country. It is also due to the fact that the regime in Pyongyang is truly unique. When one analyzes Syria’s dictator Bashar al-Assad, for example, parallels can be drawn to other Middle Eastern autocrats like Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi. To understand the phenomenon of Venezuela’s despot Nicolas Maduro, references to other caudillos, like Fidel Castro or Juan Peron, can be made. Kim Jong-un stands alone.

Historical baggage

No other country in the world has a political system even remotely similar to North Korea’s. One key element is that the regime is a Confucian monarchy, founded by the eternal Kim Il Sung, who established the dynasty and ruled from 1948 to 1994. In addition, the oppressive system in North Korea is Stalinist in its nature. Then, there is an oligarchy occupying the upper echelons of the ruling party, the military and the state. Finally, the ambiance in the country reminds one of something akin to a sect.

The deep wounds caused by World War II and by the Korean War have not been healed in the Far East.

While the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is most certainly an enigma, the motive that drives the North Korean leadership in their pursuit of nuclear warheads and of long-range ballistic missiles is not. The regime in Pyongyang has learned its lesson from recent history in the Middle East. Kim Jong-un has seen that regime change became possible in Libya and Iraq because neither Muammar Qaddafi nor Saddam Hussein possessed nuclear weapons. Would the West have acted in the same assertive way, if these two states could have resorted to nuclear retaliation in the case of being invaded by foreign armies?

To shed some light on possible scenarios for the Korean Peninsula, one needs to take into account history, geopolitics and system survival. History has a continuous presence in today’s politics in the Far East. This is so, because the deep wounds caused by World War II and by the Korean War have not been healed. Europeans, in particular, should know the weight of historical baggage and the value of dealing with it in a competent, constructive way. No sane person will doubt that the reconciliation between France and Germany has been an anchor of peace and stability in continental Europe. This kind of reconciliation has not happened in the Far East: not between China and Japan, not between the two Koreas, not between North Korea and Japan, not between South Korea and Japan, and not between the Koreans and the Chinese.

Unexpected turns

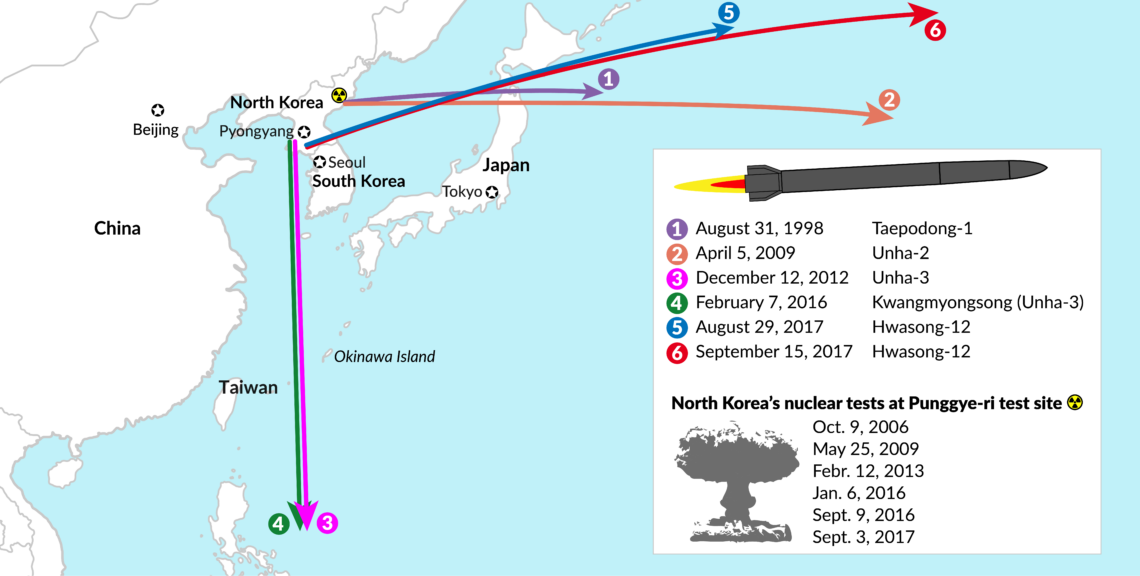

In the light of this, North Korea’s nuclear ambitions are a particularly explosive issue. Beijing keeps advocating a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula knowing fully well that North Korea’s acceptance as a nuclear state would over time motivate South Korea and Japan to acquire their own nuclear capabilities. In the case of Japan, the nation’s technical prowess would allow it to become a major nuclear power very fast. If South Korea went down the same path, a dangerous arms race and high volatility in the region would be the result.

Most recently, there have been both instances of bellicose language as well as cautious conciliatory steps in the conflict over North Korea’s military posture. When it comes to the United States, Pyongyang’s rhetoric knows no limits and is sometimes met with equally childish and provocative language from U.S. President Donald Trump.

For a long time, it looked as if North Korea was bent on ruining the atmosphere of the 18th Winter Olympics hosted by South Korea in the mountain resort of Pyeongchang. Pyongyang has played the spoiler in the past. In 2002, when a world football championship was hosted jointly in South Korea and Japan, the originally planned transmission of matches to North Korea was suddenly canceled by the regime. (In another context, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who originally was not going to attend the Winter Olympics because of friction between Japan and South Korea over the “comfort women” issue, remarkably reversed his position.)

As it turned out, the Pyeongchang games were the scene of some surprising gestures from the North, including the appearance of the dictator’s sister at its opening ceremony. This charm offensive, however, hardly altered things on the ground. The Korean Peninsula continues to be the most dangerous crisis spot on the globe. While it is impossible to get a clear picture of what the North Korean government is planning next, the positions of the major political forces in South Korea are much clearer. For a long time, there have been conservative and progressive camps. The conservatives were in power under President Park Geun-hye from 2013 until her unceremonious dismissal in spring 2017. She has been replaced by a progressive liberal, Moon Jae-in.

The South’s quandary

Of course, relations with the North are South Korea’s national issue, where party politics plays a limited role. Nevertheless, liberal South Korean politicians traditionally have favored a softer approach. The first South Korean president to visit North Korea (in 2000), former dissident Kim Dae-jung, even received the Nobel Peace Prize for that decision. His critics would soon see their skepticism about the North vindicated, as the visit did not lead to any lasting detente between the two countries. On the watch of Ms. Park (whose father Park Chung-hee had dominated South Korea from 1962 until his assassination in 1979), relations with the North hit a new low. Only recently, under President Moon Jae-in, has there been some easing of tensions.

The key to the enigma of North Korea’s security policy is in China’s hands.

While reasonable people are keen to restore calm to the Korean Peninsula, President Moon’s position has not won universal approval. Influential voices are criticizing his attitude as too weak toward Pyongyang. Some critics believe that he has been too quick to give Kim Jong-un a platform. As in the past, the question remains whether South Korea will find its open attitude toward the North rewarded in any way. Sudden turnarounds in these relations, seen repeatedly in the past, provide ammunition to the skeptics.

Scenario: ‘manageable crises’

Looking into the future, it should first be emphasized that, more than ever before, the key to the enigma of North Korea’s security policy is in China’s hands. The Trump administration’s heated rhetoric may on occasion add fuel to the fire, but there are no reliable indications that it is any closer to containing the dictator’s nuclear and missile programs than its predecessors. This skepticism applies to an open military confrontation as well: no one but the most rabid warmonger would see such an option as anything but a nonstarter, far too costly not only for all South Koreans but also for the locally deployed American forces.

If Beijing holds the key, one must carefully analyze the signals coming from the Chinese leadership, most notably President Xi Jinping. The most important signal came last November, when President Xi consolidated and extended his five-year rule at the19th Chinese Communist Party Congress. Having collected the country’s most influential power positions, both civilian and military, party and state, Mr. Xi is poised to run China for far longer than another five-year term. He now has an even greater vested interest in stability. Recent signals about a substantial thaw in China’s bilateral relations with Japan point in this direction. In this scheme of things, it matters that Prime Minister Abe won a clear mandate in the lower house during the October 2017 snap elections. This means that Japan, too, has a government that can afford to take a longer view in its foreign and security policies.

Putting these puzzle pieces together, one concludes that the most likely scenario is for China to continue making sure that no systemic disaster befalls Pyongyang. For example, whatever sanctions remain in place, Beijing will prevent them from producing a collapse of the North Korean regime. At the same time, the Chinese will be careful to contain any fallout from the crises that are likely to break out from time to time, such as missile launches or nuclear tests by the North. Obviously, Beijing is fully aware that Kim Jong-un sees these missile and nuclear programs as his regime’s ultimate life insurance and an asset he will not give up under any circumstances.

For this scenario of “manageable crises,” constructive relations between China, South Korea and Japan are crucial. It is therefore a positive sign that trilateral summits between these neighbors are going to resume, as both the Japanese and Chinese media report. Bearing in mind the complexity of the security issues in the Far East, nobody should expect radical or even substantial moves. The best hope is for an incremental easing of tension. Pyongyang is a keen and competent observer of security concerns and political shifts in the region and beyond. The possible gains from greater predictability and a longer-term view emerging from consolidation of political power in Seoul, Tokyo and Beijing may not be entirely lost on Pyongyang, too.