Corruption in Latin America

The Odebrecht scandal, which started off as the Petrobras scandal in Brazil, has sent ripple effects throughout Latin America. It has brought down some regimes and even landed powerful leaders in jail. Perhaps the most important result is voters’ distrust of the traditional political forces.

In a nutshell

- The Odebrecht scandal has tainted nearly every government in Latin America

- Those less affected are in countries where the rule of law is strong

- Voter anger is leading to sweeping political change throughout the region

- Economies may sputter as governments scale back infrastructure investments

When the Worker’s Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT) came to power in Brazil in 2003, it and newly elected President Luis Inacio “Lula” da Silva rode a furious wave of anti-corruption sentiment. Finally, the PT promised, Brazil’s endemic, seemingly intractable corruption would be put to an end, thanks to a party committed to ethical, by-the-book governance. A new era seemed to be opening in Brazilian politics.

That story, we now know, was a fraud. Under the PT’s watch, corruption flourished. In fact, it spread on a vast scale across Latin America. The depth and breadth of the so-called Odebrecht scandal, which originated in Brazil and ensnared numerous Brazilian politicians and executives, has become the defining event of the past decade in the region.

The scandal is named for the construction company that was once was the hemisphere’s largest. Odebrecht served as the conduit for millions of dollars in bribes, much of it taken from the Brazilian national petroleum company, Petrobras. Almost three years after the scheme was first uncovered, new revelations about the extent of Odebrecht-related corruption continue to emerge. The episode will undoubtedly have lasting consequences for Latin American’s economy and political system.

The Odebrecht scandal began as the Petrobras scandal, as the Brazilian oil and gas company was looted of vast sums – estimated at nearly $5 billion – by PT members under Lula’s administration. The money went to party activists and members of congress whose votes were necessary to pass legislation. This financial drain virtually paralyzed Petrobras: production stagnated for two years and the company could not tap the international capital markets until late 2017, when it managed to resume normal activity. Odebrecht dipped into the illicit money flows through the vast construction contracts it held with Petrobras. From there, it was a relatively simple step to use the construction company’s vast network of contacts and contracts to bribe officials throughout the region.

At the heart of the Odebrecht scheme was an ingenious mechanism to win huge government infrastructure contracts.

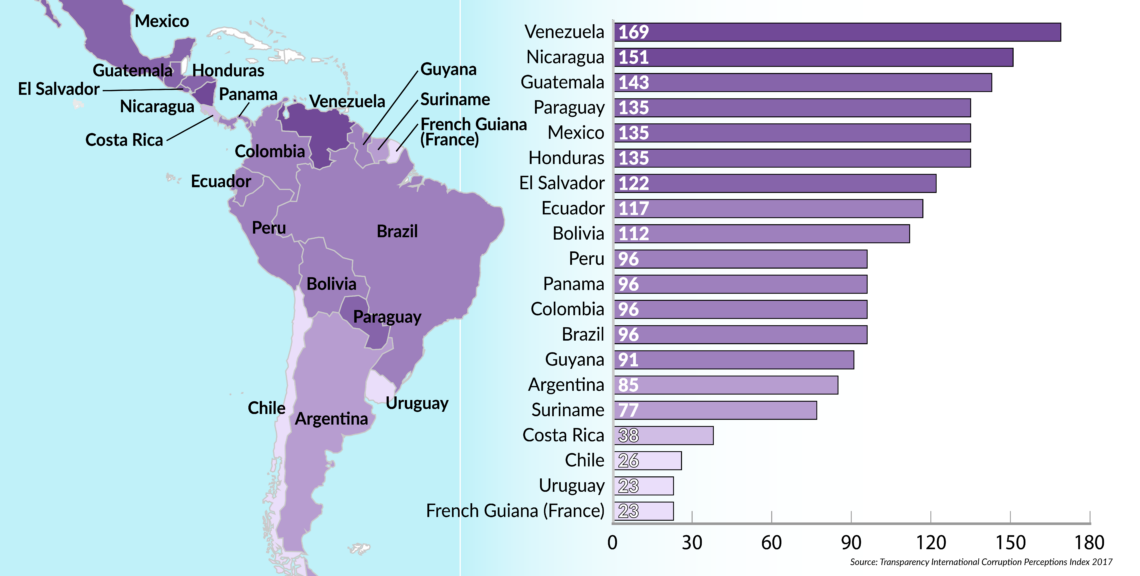

In February, Transparency International, a Berlin-based corruption watchdog, released its annual Corruption Perceptions Index, which ranks countries by their level of corruption as perceived by experts in business and governance. Except for Uruguay (which ranked 26th out of 180 countries), Chile (which ranked 28th), and Costa Rica (which ranked 38th), Latin America fares poorly in the rankings. These also happen to be the countries that were least affected by the Odebrecht scandal.

At the heart of the Odebrecht scheme was an ingenious mechanism to win huge government infrastructure contracts and then squeeze extra money out of them. Typically, Odebrecht would put in the lowest bid in a public-private partnership tender. Then, having won the contract, the company would start padding the costs through fictitious addenda, which were subject to considerably less oversight. Securing the approval of these expensive add-ons required a network of well-placed bribes. In total, Odebrecht is estimated to have paid $800 million in bribes across Latin America. The company has already agreed to an unprecedented $3.5 billion fine, and nearly 100 Odebrecht executives are cooperating with the authorities in exchange for reduced sentences. The tangled scheme is still being unraveled.

Brazil

In Brazil, which is tied with Peru, Colombia and Panama for 96th on Transparency International’s list, the Odebrecht scandal has triggered a nearly complete political collapse. Presidential elections will take place in October. Former President Lula has announced his candidacy, despite being formally barred from running due to a corruption conviction. That conviction was unanimously upheld by an appeals court in January, and Brazil’s Supreme Court ordered that he begin serving a 12-year prison sentence earlier this month, while he continues the appeals process.

In a political system so rife with corruption – most of Brazil’s prominent politicians are facing accusations of some kind – this is certain to anger the Brazilians who still revere Lula. To them, Lula’s conviction on what they consider a relatively minor corruption charge smacks of a political power play. The left has no other candidate with Lula’s name recognition or popularity.

If Lula’s corruption charge is not overturned, the results for the coming elections would be twofold. First, there would be a deep sense of illegitimacy among Lula’s supporters. “Either Lula is a candidate, or we are going out on the streets,” has been a common refrain from PT leaders. Second, the campaign would be an opportunity for a non-PT figure to emerge victorious for the first time in more than 15 years. Brazil’s system of political alliances could be fundamentally reshaped without Lula providing glue to hold the old coalitions together.

Peru

In Peru, also in the four-way tie for 96th on the Transparency International list, the Odebrecht scandal has already led to the imprisonment of two former presidents and the downfall of a third. In December 2017, then-President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (known as PPK) narrowly avoided impeachment after connections were discovered between Odebrecht and his business empire. Mr. Kuczynski had denied ever having done business with Odebrecht.

Nonetheless, he survived the impeachment vote by offering the opposition a quid pro quo pardon of imprisoned former President Alberto Fujimori. That devil’s bargain infuriated President Kuczynski’s supporters, who had elected him largely on the premise that he would not pardon Mr. Fujimori. In March this year, President Kuczynski again came under fire after Jorge Barata, formerly Odebrecht’s top executive in Peru, testified that he sent money to Mr. Kuczynski’s 2011 presidential campaign. He also admitted to sending Odebrecht money to opposition campaigns. PPK fell when videos were made public of his allies trying to buy the votes of opposition lawmakers in the congress.

In its rush to distance itself from Odebrecht, the Peruvian government canceled or suspended several large infrastructure projects.

Moreover, in its rush to distance itself from Odebrecht, the Peruvian government canceled or suspended several large infrastructure projects, dampening the nation’s economic growth by nearly 1 percent for fiscal year 2017. The government referred to this slowdown as the “Odebrecht effect.” Scaling back infrastructure projects in other countries will no doubt have a similar impact.

Ecuador

In Ecuador, ranked 117th by Transparency International, former Vice President Jorge Glas has been sentenced to six years in prison for his involvement in the Odebrecht scandal. It is estimated that Odebrecht spent $33.6 million on bribes in Ecuador alone to secure its projects. As vice president, Mr. Glas headed the Coordinating Ministry for Strategic Sectors, a department that oversaw major infrastructure investments. Among the Odebrecht projects found to have resulted from bribes are a hydroelectric dam, a major aqueduct and a refinery. None of these projects has been completed.

Mexico

In Mexico, ranked 135th on Transparency International’s index, President Enrique Pena Nieto’s administration has been the object of numerous corruption allegations, some relating to the Odebrecht scandal and some completely separate. Most notably, Mr. Pena Nieto’s campaign advisor, Emilio Lozoya, who subsequently became director of the state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), has been linked to over $10 million in bribes from Odebrecht, some of which was allegedly funneled into Mr. Pena Nieto’s campaign funds. The president himself is not clear of suspicion, either. His wife was forced to return a house worth more than $1 million, which had been purchased for her by a construction company. Others in his entourage have been implicated in corruption.

In response to these and other accusations, Mr. Pena Nieto reluctantly supported the creation of an anti-corruption watchdog group – with which he has subsequently refused to cooperate. Now, with presidential elections approaching in July, the three leading candidates all face corruption allegations.

A general election for the congress will be held at the same time. Candidates from the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) will face a tough road; auditors investigating Mexico’s finances between 2012 and 2016 have found nearly $375 million in diverted and misused funds, clearly cementing the PRI’s reputation as a bastion of corruption and kickbacks. No fewer than 16 state governors, almost all from the PRI, have either resigned, been indicted or are under threat of extradition to the United States on charges of corruption.

Underlying this pattern of public corruption is the open secret of drug cartels bribing local police and regional governments to buy their safety. The northeast of the country, for example, is dangerously close to becoming a narco-region where local governments are in the pocket of the drug traffickers.

Argentina

In Argentina, President Mauricio Macri used the corruption of his predecessor, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, as a powerful campaign weapon. Now in power, he is encouraging the judiciary to get on with the job of bringing her to justice. The extent of her corruption is not fully known, but it is estimated that between fraudulent real estate deals, money laundering and assorted schemes, the total could reach $2 billion.

Driving the anti-corruption campaign full-throttle has not been one of President Macri’s priorities.

The problem for Mr. Macri, in part, is that his own family fortune is hidden offshore and was revealed in the so-called Panama Papers leak. Congress (including members of his governing coalition) has demanded that someone from his cabinet testify as to the nature of his offshore accounts. Driving the anti-corruption campaign full-throttle has therefore not been one of his priorities.

Venezuela

Part of the difficulty in negotiating a peaceful transition to a more democratic government in Venezuela is the rumor, backed by assertions made public by the U.S. Treasury and Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), that key members of the Nicolas Maduro government are deeply involved in drug trafficking, in partnership with Colombian cartels. Others in the government have been accused of skimming public funds from programs to distribute food and medicine to the poor, especially in Caracas, where votes have been purchased for years in this way. To the extent that these rumors and accusations are true, the exit scenario for the Maduro government and its military allies becomes more difficult.

Lasting consequences

Looking forward, the Odebrecht scandal will have deep and lasting consequences for Latin American economies and political systems. Economically, perhaps the biggest risk (looking beyond short-term reductions in gross domestic product) is that much-needed infrastructure projects may be slowed or eliminated due to public skepticism about their worth.

A second long-term effect of the Odebrecht scandal may be to favor extremist candidates claiming to be “outsiders” who will put an end to corruption. In Brazil, where anti-corruption legislation has floundered in congress, despite being specifically recommended by the judicial task force that uncovered the Odebrecht scheme, it would be understandable for the public to conclude that more extreme, outside voices will act more bravely.

That tendency may explain the bizarre rise of far-right Congressman Jair Bolsonaro, currently running second in presidential election polling. “He is the only politician who has not stolen,” Mr. Bolsonaro’s supporters often claim. A search for Trump-like outsider candidates could inject new blood into the Brazilian political system, but also risks bringing an extremist to power due to loss of confidence in the existing mainstream parties.

A similar dynamic may be at work in Mexico, where Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has emerged as the leading candidate, claiming that he alone, as a maverick, can end Mexico’s endemic corruption.

Corruption is not cultural nor is it racial or gender specific. It is a function of weak government institutions and a lack of accountability. In countries where a small oligarchy, generally a landed elite, has held power over a long period more or less legitimately, they develop a powerful sense of entitlement to get what they want or need by any means. In several countries, this mode of semi-democratic government goes back generations.

Putting institutions in place that can provide oversight and accountability will not be easy. The power of groups like Transparency International, the European Union, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – which value the campaign to eliminate government corruption – is growing in the region. Specifically, Argentina and Colombia are making anti-corruption promises part of their applications to the OECD. And Argentina, as host for the G20 meeting at the end of this year, wants to improve its image among the world’s leading powers.

To the extent that the countries of Latin America want to be part of the larger global community, the malaise of corruption is a hindrance. It is also a powerful drag on economic development.