The fragile state of Pakistan

Economic, political and security challenges are mounting for Islamabad ahead of general elections expected in October. The prospect of military interference looms large.

In a nutshell

- Severe flooding compounded problems for a weak and indebted economy

- The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan has exacerbated security challenges

- Pakistan’s embrace of China cools relations with United States and India

Pakistan enters 2023 in a perilous state. The coalition government that took over in April 2022 is finding it difficult to calm domestic politics, rescue the economy, bolster national security and craft effective foreign policy in the nuclear-armed South Asian nation of 231 million people.

The country’s all-powerful army has a new chief after six years, but it is not clear how he might influence the course of events. The fiery rhetoric of populist former Prime Minister Imran Khan, banned from holding elected office for five years because of alleged campaign finance violations, has cooled somewhat. But his attempts to dissolve two provincial assemblies where his party is in power are stoking political instability.

In August 2022, the $1.1 billion tranche of the International Monetary Fund bailout loan failed to stabilize Pakistan’s economy. The next tranche in the $7 billion agreement is on hold amid fears that yet another bailout may be needed in the near future.

The return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan has created more dangers. A resurgent Pakistani Taliban has launched attacks across the nation, including a suicide bombing in the capital Islamabad. Pakistan’s relations with India are frozen in time, with the constant possibility of a flare-up in the event of a terror attack.

Pakistan’s strategic embrace of China at a time when the United States views Beijing as a competitor complicates Islamabad’s preferred policy of seeking a balance between the two global powers.

Ex-premier Khan stokes political volatility

Last year witnessed heated political struggles featuring Mr. Khan, the cricketer-turned-politician. He has been battling other political parties, the judiciary and the military-intelligence establishment, which engaged in behind-the-scenes manipulation to sideline him. Unable to countenance losing a vote of no confidence in parliament in April 2022, Mr. Khan spent the next few months firing up his supporters with unsubstantiated claims of a U.S.-backed conspiracy against him involving the top brass of the Pakistan army.

Mr. Khan’s hope is to force early general elections and ride a wave of popularity to a parliamentary majority for his party and select the next army chief. But his actions have damaged Pakistan’s relations with the U.S., deepened the political chaos and worsened the economic crises. And he has so far failed in his aim.

Mr. Khan’s rhetoric softened a bit following gunshot wounds sustained after an assassination attempt at one of his rallies on November 3, 2022. He is now seeking early elections in two provinces where his party currently holds a majority – Punjab, Pakistan’s largest province, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. While the chief ministers of both provinces are reluctant to dissolve provincial assemblies, Mr. Khan’s activities will ensure continued chaos, with moves and countermoves both in the provincial assembly and the court.

The coalition government led by Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) has found it difficult to govern or improve the economy, beset by a persistent balance-of-payments crisis. The August 2022 tranche of the bailout loan from the IMF staved off default. But while the government initially agreed to the strict IMF conditions, it now is insisting it cannot implement tough reform measures, including erasing chronic debts in the energy sector.

Rising debt and sluggish economy

Pakistan has seldom fulfilled IMF conditions. But unlike the previous 22 times since 1959, the IMF is now less willing to make concessions and reluctant to release the next tranche unless the government keeps its promises. An oft-announced $13 billion loan from Saudi Arabia and China has yet to materialize and, even if it did, it will only add to the country’s $130 billion debt in a country with only a $376 billion economy in 2022 – amounting to just over $5,000 per person, even when purchasing power parity is factored in. The nation, meanwhile, is making plans to go another $10 billion in debt to China with a significant upgrade of the national railway.

Extensive flooding in 2022, brought on by monsoon rains and melting glaciers, killed 1,700 people and caused billions of dollars in damage.

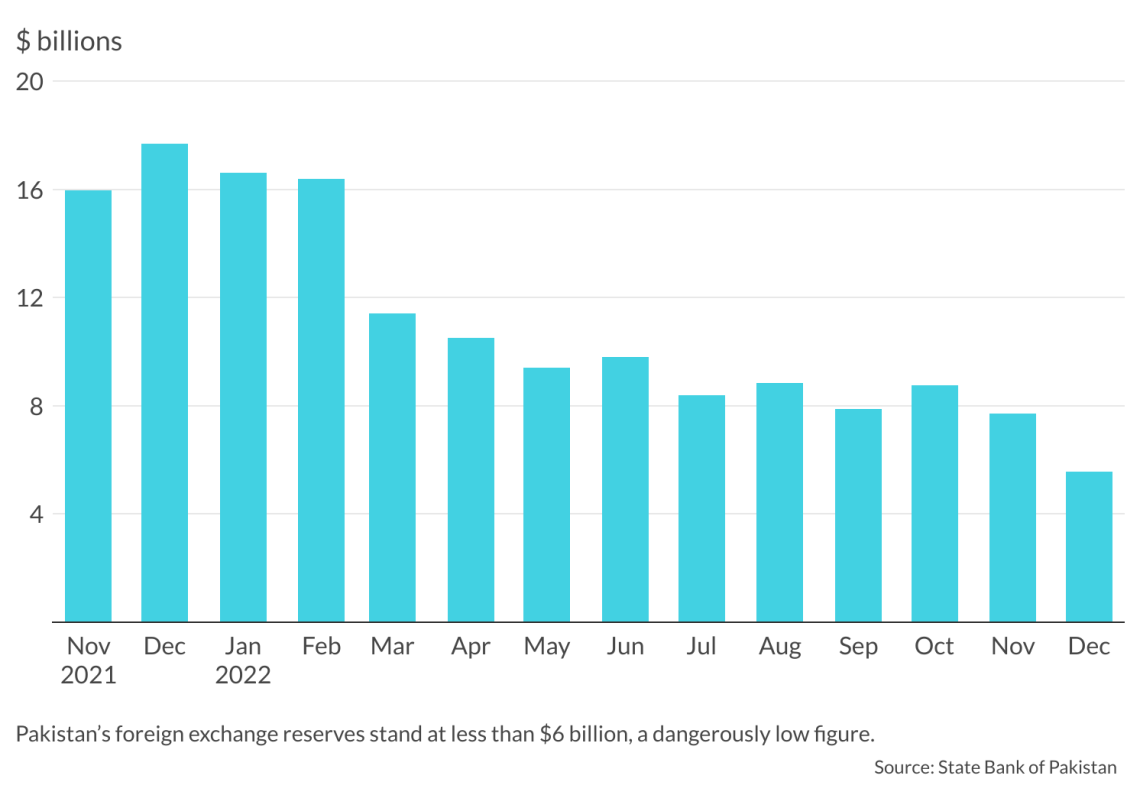

In 2022, Pakistan’s economy grew at an abysmal 2 percent and its foreign reserves now stand at a perilously low amount of less than $6 billion, not enough to cover even one month of imports. Extensive flooding in 2022, brought on by monsoon rains and melting glaciers, killed 1,700 people and caused billions of dollars in damage. The waters devastated agriculture and livestock, infrastructure and two million homes. Unable to get access to electricity and natural gas, many industries including Pakistan’s primary export – textiles – shut down their factories. Pakistan is seeking a $16 billion flood-relief package from international donors.

If the economy does not improve before the next general election, currently scheduled for October, the electorate will likely forget Mr. Khan’s role in causing the economic crisis, leaving the incumbent government with all the blame. The PMLN hopes that the impending return to Pakistan of exiled three-time prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, will galvanize their base and lead them to electoral success.

Whether that happens may depend to a large extent on two actors – the judiciary and the military – both of whom would prefer a weak coalition government to a PMLN majority government.

Read more by Aparna Pande

Crisis and instability threaten Pakistan’s economy yet again

New army chief

After six years, Pakistan has a new army chief, General Asim Munir Shah. The new chief is a dyed-in-the-wool institution man. He is also the first army chief to have been head of both Military Intelligence and Inter-Services Intelligence. Like army chiefs before him, who took office following either direct military rule or public interference by the army, General Munir will seek to lower the military’s public profile. This does not mean that the army or intelligence services will stop their interference, but rather they will do so in a more subtle manner.

The Pakistan army views itself as the nation’s savior and prides itself on its popularity. The institution is therefore concerned by the vitriolic public criticism of Mr. Khan’s supporters, some of whom have military backgrounds. General Munir may prefer to follow Ashfaq Parvez Kayani (2008-2013) – also a former intelligence chief – who became army chief after Pervez Musharraf’s dictatorship and undertook a similar lowering of the military’s profile.

The appointment of a new army chief will not resolve Pakistan’s security challenges. The return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan in August 2021 was viewed by the Pakistani army and intelligence establishment as its victory. Pakistan’s policy in Afghanistan had centered on ensuring a pro-Pakistan, anti-Indian, Islamist, Pashtun regime. This victory has, however, turned out to be pyrrhic.

The Taliban challenge

The Taliban’s reluctance to soften their ideological beliefs – whether on gender rights or other issues – means Afghanistan is now receiving only basic international humanitarian aid. In effect, Pakistan is having to carry the burden of not just its own economy but that of Afghanistan.

The Afghan Taliban are also proving to be challenging allies for Pakistan. There are regular skirmishes along the border with mounting casualties. The Taliban are also unable to provide security, highlighted by an attack on Pakistan’s Embassy in Kabul by the Islamic State – Khorasan Province (IS-KP) in early December.

The most likely scenario is that the coalition government will muddle along, helped by a military establishment and judiciary that seek stability to ensure an easing of Pakistan’s economic suffering.

Pakistan’s internal security has worsened ever since the resurgence of the Taliban, especially attacks by the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). In June 2022 the TTP agreed to a temporary cease-fire with the Pakistani government but in November they reneged on that and unleashed a series of attacks targeting Pakistan’s security forces. The TTP militants appear better armed, thanks to support from their Afghan counterparts. Fervent diplomatic engagement by Pakistan has yet to bear fruit.

Facts & figures

Cooler relations with the U.S.

U.S.-Pakistan relations are in a better place than in early 2022 but they are far cooler than Pakistan desires – a function of Pakistan’s close relations with China and the U.S. shift to India as its partner of choice in the competition with China. Pakistan remains as close, if not closer, to China than before and its adversarial view of India has not changed. The coalition government has raised the rhetoric against India.

Scenarios

The key actors in Pakistan remain the same: the political parties, the military-intelligence establishment and the judiciary. Pakistan’s constitution requires that elections, likely in October, be organized by a caretaker government appointed by the president after consultation with the prime minister and the leader of the opposition. If there is no consensus, the president appoints a caretaker prime minister in consultation with the Election Commission of Pakistan. Historically, technocrats or retired justices have been the preferred candidates for a caretaker government. This government stays in power for around two or three months to ensure free and fair elections are held.

The most likely scenario is that the coalition government will muddle along, helped by a military establishment and judiciary that seek stability to ensure an easing of Pakistan’s economic suffering.

If the army avoids overt interference of the kind that took place in 2018, like in 2008 and 2013, then there is a likelihood of reasonably free and fair elections.

In an honest contest, the current coalition is likely to return to power, barring the possibility that PMLN sweeps the polls and secures an absolute majority, as happened in 1997 and 2013. Pakistan’s security establishment would prefer a coalition government to a PMLN majority and is likely to work behind the scenes to ensure that outcome. There is a small chance that they could just let the chips fall as they may.

The less likely scenario is that Mr. Khan retains his popularity, and the continued crises allow his party to emerge victorious. As of now, he has been disqualified for five years because of illegal electoral financing. For the ex-prime minister to run and win, he would have to avoid imprisonment and win relief in the courts. In this event, the role of the judiciary and military establishment will be critical.

The least likely scenario remains the possibility that the risk of economic collapse prompts the army leadership to step in. They could, then, impose an interim caretaker government that implements tough economic measures and helps get the economy back on track before holding elections. The likelihood of a direct military coup remains low unless the situation becomes so dire that the army believes that is the only option left.