Scenarios for African migration to Europe

European Union member states will have to negotiate a new pact on migration and asylum amid economic and political insecurity. The latest EU strategy revolves around reinforced border security in Africa to contain a potential post-pandemic migration spike.

In a nutshell

- Migration flows from Africa decreased before the pandemic

- More Africans could seek asylum due to security threats

- Third-party countries’ cooperation will prove crucial

Irregular arrivals into the European Union have been decreasing since 2015. In 2019, FRONTEX detected 141, 846 illegal border crossings along the EU external borders, a 92 percent decrease compared to 2015 when there were 1.8 million such incidents. However, migration management will remain a pressing and contentious issue.

EU member states will soon negotiate a new pact on migration and asylum in a volatile and delicate economic and geopolitical context. In addition to the short and medium-term effects of the Covid 19 pandemic, the security outlook is worsening in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa, so preparation for a potential post-pandemic migration spike is vital.

Facts & figures

Recent trends

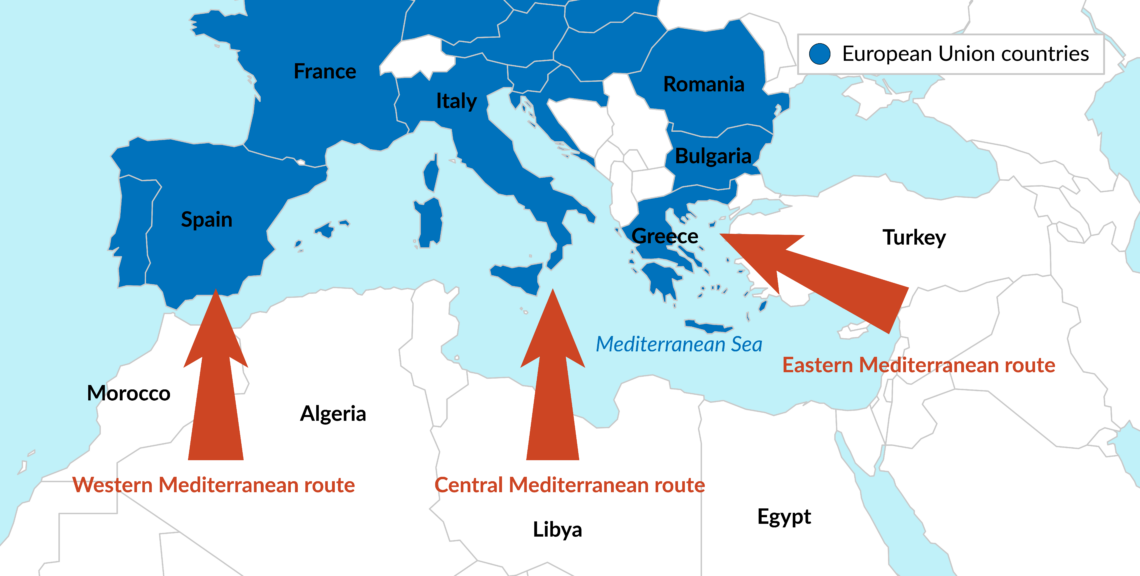

The year 2019 was characterized by a significant decrease in the number of irregular arrivals from Africa, in particular through the Western and Central Mediterranean route. (The number of migrants crossing through the Eastern Mediterranean route, however, has increased.) This trend reflects the effectiveness of border control measures and partnerships with origin and transit countries like Libya and Morocco. During the first six months of 2020, the number continued to decrease, mostly due to mobility restrictions implemented throughout the African continent and along the EU borders to contain the coronavirus.

In West and Central Africa, for example, regional migration flows have decreased by almost 50 percent. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) closed its internal and external borders for the first time in four decades. However, people continued to migrate and restrictions in key transit countries like Niger, Sudan, Ethiopia or Djibouti have led to a sharp increase in the number of stranded migrants. In Libya, where there are over 600,000 registered migrants and refugees coming mainly from Sudan, Chad, Egypt and Niger, the situation is particularly critical. In May, the number of migrants trying to enter the EU tripled, suggesting that as the obstacles to mobility to contain Covid-19 are removed, migration from Africa in a post-pandemic era will increase pressure on the EU external borders.

In 2019, Morocco managed to dismantle several human smuggling networks.

Also relevant is the fact that over the past years, the proportion of migrants eligible for asylum under EU criteria has been decreasing. In 2019, 612, 700 first-time asylum seekers applied for international protection in EU countries. The majority of applicants were from Syria, Afghanistan, and Venezuela, with Germany, France and Spain as the main destination countries. Approximately 38 percent of asylum requests were accepted. With regard to Africa, in July 2020, the highest number of asylum requests came from Nigerian, Somalian and Guinean citizens. Recognition rates for these requests were 11, 51 and 19 percent, respectively.

However, given the political and humanitarian issues in the Sahel – civil war in Mali, conflict in Burkina Faso and volatile situations in Niger and Chad – the already high number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees in the region will go up. While the vast majority of these IDPs and refugees will remain in the region, rising poverty, hunger and crime will collide with the EU’s ambitions to manage migration flows from the African continent.

The number of migrants and asylum seekers from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, driven mainly by economic reasons, is also rising. In June 2020, they accounted for a third of all African migrants arriving through Italy and Spain. In 2018, Spain became the main point of arrival for migrants coming from the Maghreb and West African countries – a result of increased patrolling activities by the Libyan coast guard along the Central Mediterranean route.

Between January and August 2020, Algerians and Moroccans accounted for more than 56 percent of arrivals by sea. Consequently, the Western Mediterranean route is becoming more expensive and dangerous for migrants, especially those coming from sub-Saharan Africa. In 2019, Moroccan authorities managed to dismantle several human smuggling networks. Migrants, in turn, are sent back to the country’s southern borders. Flows along the Eastern Mediterranean route have also increased in 2019, mainly consisting of Afghans, Syrians and Turks – at a time when relations between Brussels and Ankara are at a critical low.

Compromise solution

While there is much continuity, the New Migration and Asylum Pact recently presented by the EU commission introduces changes to both the rhetoric and practical approach. Emphasizing the differences between the 2015 humanitarian catastrophe and the more complex challenges of 2020, the document states that migration is both inevitable and positive if “well managed.” The new pact attempts to balance humanitarian goals, protectionist instincts and practical limits to the EU’s integration capacity.

The agreement seems to be undergirded by two ideas. First, “unmanaged” migration represents a threat not only to security but also to the EU political project, and different sensibilities on the matter must be granted recognition. Second, the current system no longer works – as acknowledged by European Commissioner for Promoting the European Way of Life Margaritis Schinas.

In practice, the pact confirms the reinforcement of border security cooperation with third-party countries. Despite the fragility of existing arrangements, the strategy has effectively contained migratory pressure in the past. In Niger, for example, the EU Capacity Building Mission (EUCAP- Sahel Niger) established in 2012 has been mandated to collaborate on migration management efforts, whereas FRONTEX has deployed a liaison officer in Niamey in 2017. Migratory flows through Agadez, a major transit point in the Sahel, have dropped by 75 percent.

The situation is problematic when it comes to subsidizing states like Libya, where power is disputed.

Given the rigid position on migration and asylum matters adopted by countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia and their reaction to the pact (sponsored by Germany and France), the negotiating process will likely be challenging. While welcoming the elimination of mandatory quotas and the emphasis on repatriation efficiency, these countries – Hungary in particular – insist on the need to establish processing centers for asylum seekers outside EU borders.

While collaboration on migration and asylum is mandatory and the amount due is calculated based on the gross domestic product (GDP) and population size, the proposed agreement gives member countries the possibility to choose how they collaborate. This flexibility is intended to address the disproportionate price paid by countries of entry, especially Greece and Italy, while offering acceptable options for countries that refuse mandatory relocation quotas.

Options include providing immediate operational support or taking responsibility for the return of rejected asylum seekers. The pact also earmarks 10,000 euros per refugee for member states. This solution may be attractive for countries like Portugal, where migration is not – at least not yet – a highly contentious or destabilizing factor.

Difficult partnerships

Finding a common migration policy within the EU has proven an arduous task. Implementing a joint strategy with origin and transit countries will be no less challenging. Such cooperation frameworks may generate unintended consequences that collide with the EU’s core values, and their efficiency depends on factors which are, to a great extent, beyond the EU’s control.

In some cases, diplomatic incentives like financial rewards or visa allocations will be sufficient to establish successful collaborations. For example, in 2019, the EU announced a 101.7 million-euro package to support Morocco in combatting human smuggling and managing irregular migration.

However, the situation is more problematic when it comes to subsidizing states like Libya, where power is disputed by different militias. Despite the cease-fire announced in August, the problem remains critical. The migrant smuggling business has expanded, generating a complex network connecting local militias, security officers and transnational criminal organizations. As the number of migrants stranded in the country increased, so did the number of detention centers, where detainees are exposed to extortion, violence or forced labor.

Scenarios

Migratory pressure on EU borders will remain, as the number of asylum seekers will continue to widely exceed the number of people the Union is willing or capable of accommodating. The effectiveness of containment strategies will depend on factors beyond EU control, not least the political will and stability of third-party states. In this sense, the EU-AU summit, which was delayed to 2021, may prove pivotal.

Africa-EU irregular migration is mixed and includes refugees, asylum seekers, and economic migrants. Because of the complex political and security conditions of origin countries, it is difficult to differentiate between refugees escaping conflict and economic migrants.

The pull factors of Africa-EU migration are expected to further decrease in the short to medium term. Job demand remains weak in low-wage and informal sectors, and migrants may face increasing competition from local workers. The financial cost and the risks of irregular migration will stay high due to short-term mobility restrictions and the more robust containment and return policies adopted by the EU in coordination with third-party countries.

Push factors such as unemployment, income differentials, poorer health and education services, and insecurity in origin countries will also remain high. Although initial scenarios on the impact of Covid-19 in Africa were probably too pessimistic, weak growth will affect economic opportunities and development, thereby further increasing pressure on the EU with a post-pandemic migration spike.

In poorer countries where there are armed conflicts, like Chad or the Central African Republic, there could be a short- or medium-term decrease in migration, as fewer people will have the capacity to migrate. The number of refugees and IDPs will continue to increase. At the same time, asylum applications from countries in the Sahel are expected to rise in the medium term, reflecting the deterioration of humanitarian and security conditions. While less alarming, the situation in the Horn of Africa could also worsen, as overall stability depends on a political equilibrium that remains fragile.

In higher-middle and lower-middle-income countries such as Algeria, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Ghana, Nigeria, or Tunisia, the adverse economic impact of Covid-19 will likely compromise developmental gains. Faced with a combination of high unemployment, slow growth and, in many cases, political instability, the number of people willing to migrate is expected to increase. While the EU has preemptively scaled up its support to North Africa through an assistance package – to protect migrants, stabilize local communities and respond to Covid-19 – such measures are not expected to deter those who have the financial resources to migrate. Consequently, migration pressure is expected to build up as barriers to mobility are lifted.

Fragile convergence

Under this first and slightly more likely scenario, the Migration and Asylum Pact presented by the European Commission will be approved with no significant changes. The EU will manage to renew or establish cooperation partnerships with origin and transit countries. However, the mobility frameworks established with countries like Morocco, Tunisia and – albeit more reluctantly – Algeria, will have to balance the needs and aspirations of both sides.

For these countries, where large and predominantly young populations face high unemployment, emigration to Europe will remain an escape valve. These third-party states will continue to contain migration flows to Europe through both coercive and integrative means. Morocco, for example, has implemented important immigration policy reforms.

The main challenges in this scenario would be managing migratory flows from Libya and Turkey – whose ambitions sometimes collide with EU policies. Moreover, whilst effective in containing migration, such deals could have long-term adverse effects, including the perpetuation of inefficient and authoritarian regimes.

Dangerous divergence

Under this scenario, the EU would fail to implement the Migration and Asylum Pact because of internal and external divergences. The Visegrad Four would block the plan, insisting on the externalization of migration management. This remains unlikely, as African countries would oppose the approach. The African Union, in particular, would object to restrictions on mobility among member countries, at a time when the region seeks further integration, which requires freedom of movement across the continent.

Furthermore, African leaders negotiating with Brussels would meet more popular resistance, given that remittances are the primary source of foreign exchange revenue for sub-Saharan Africa and a lifeline for many families. Remittance flows to the region have already been severely affected by the pandemic, decreasing from $48 billion in 2019 to an estimated $37 billion in 2020.

As for Maghreb countries, tensions caused by the coronavirus’s adverse economic impact will likely generate more migratory pressure. Given Algeria’s and Tunisia’s fragile political situation, – governments are not expected to exert violence against citizens to contain it. The rapid deterioration of the critical humanitarian and security conditions in the Sahel, combined with a collapse of the EU migration deal with Libya or Turkey, could dramatically increase pressure on the EU’s maritime borders.