Peru’s precarious stability

Peru has outpaced its neighbors, achieving robust economic growth despite numerous political crises. Its informal economy has helped fuel that growth, but now poses a huge risk due to the coronavirus pandemic.

In a nutshell

- Peru’s economy has been growing despite political crises

- There are signs momentum could be slowing

- A unique set of challenges will test the country’s leadership

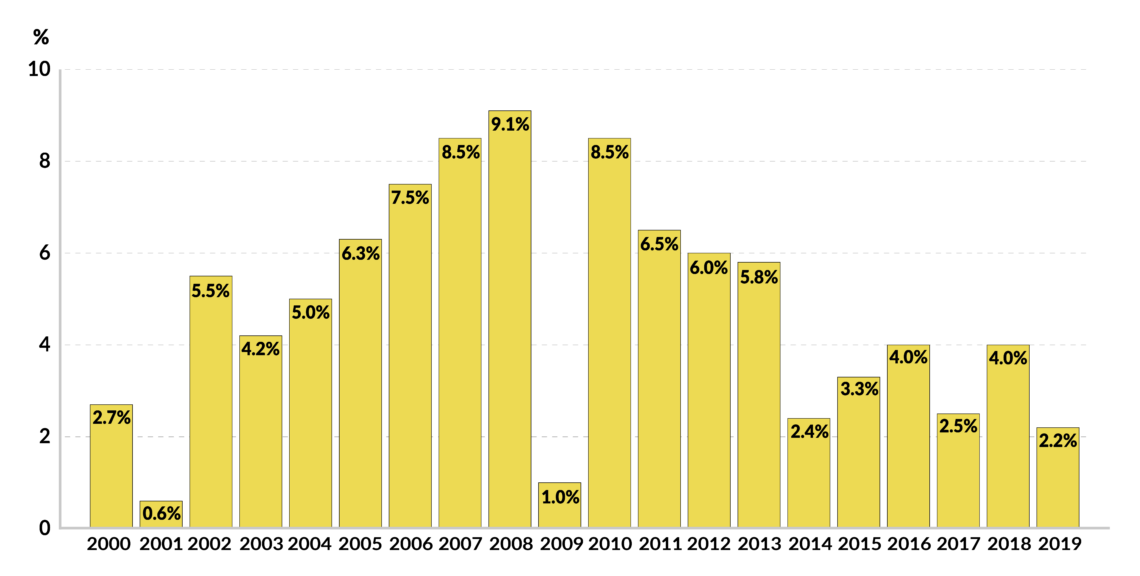

In April 2021, the people of Peru will choose their next president and members of congress, the ninth such national election since the end of the country’s military dictatorship in 1979. Over the past four decades, through rises and falls in commodity prices mainly dependent on demand from China, Peru’s economic growth has frequently outpaced the rest of Latin America. The country’s secret to success is not a unique endowment of resources, an extraordinarily talented labor force or farsighted leadership.

Instead, since 1990, Peru’s politics and economy appear to have existed in separate spheres. During this period, politics played out like a reality television show that veered between the ridiculous and the sinister, while the economy has grown steadily. No political crisis had a significant negative effect on the economy, nor did any change in leadership alter the basic shifts that began three decades ago.

Economic anomaly

The growth surge was based on two factors. First, the country started from a low base. There was a dramatic lack of infrastructure and public services, few institutions to stimulate the market and significant resources left unexploited. This general malaise became a crisis in the first presidency of Alan Garcia (1985-1990), when hyperinflation brought the economy to its knees.

In the following decade, international institutions offered aid in exchange for basic financial reforms. The government created a pension system, overhauled the tax system and made the central bank more independent. It created regulatory and oversight organizations that were crucial for the country’s development. Peru also joined several trade groups, including the Pacific Alliance.

The country’s poverty rate fell from 55 percent to 21 percent. Primary health and education services expanded to reach parts of the population that had been underserved in the past.

In the long run, informality slows down development. It signals limited state capacity and hinders the rule of law.

The second factor that separated the economy from politics is the extraordinary informality of economic activity – that is, off-the-books businesslike peddlers selling odds and ends off the street, professionals working without state licenses and unregistered businesses. In Peru, there is more informal economic activity than formal activity – estimates put approximately 60 percent of the labor force in gray-market jobs.

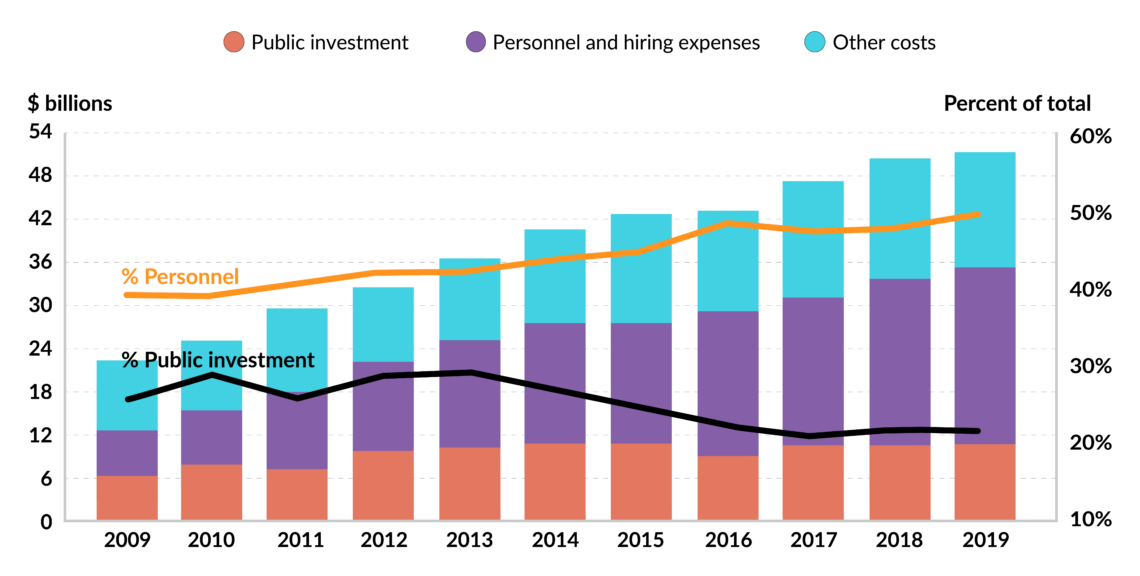

While the informality may have helped keep economic activity immune to political instability, it hurts the state’s ability to raise revenue through taxes. Almost all of Peru’s government revenue comes from indirect taxes, such as value added tax (VAT), customs duties (especially export taxes) and taxes on mining production. VAT is severely regressive while the others inhibit productive activity. Even though tax collection has improved over the past few years, the largest 80 tax-paying companies still make up nearly a third of the total business taxes collected.

In the long run, informality slows down development. It signals limited state capacity and hinders the rule of law, in addition to obvious limitations on the training of the labor force. Along with low tax collection, it undermines Peru’s competitiveness. The country’s geography is particularly challenging, making the construction of road, rail and other transport infrastructure extremely expensive. Without significant tax revenue, the government cannot afford such outlays.

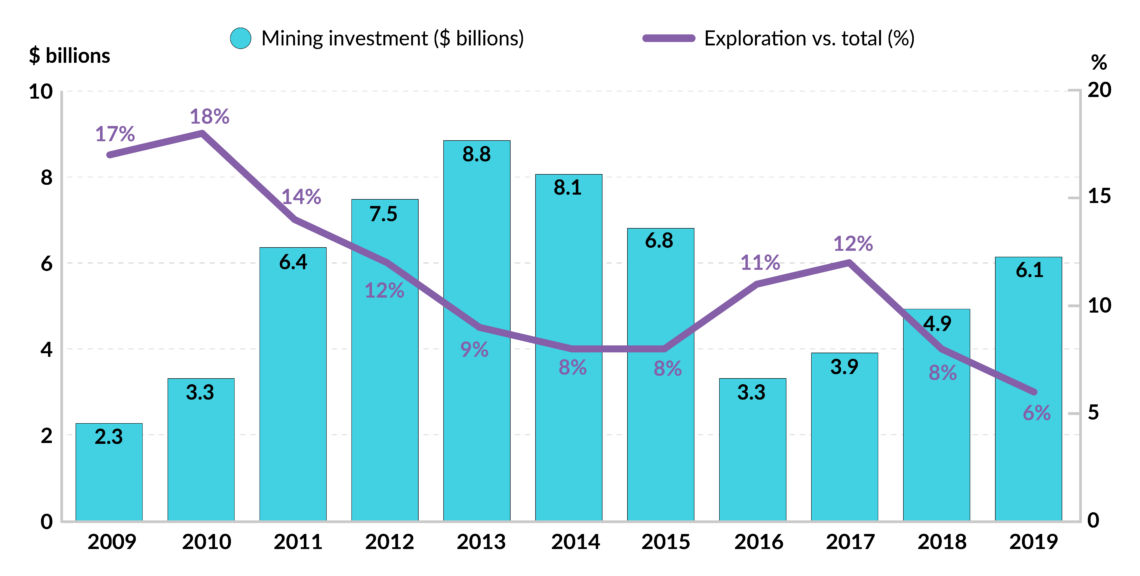

Attracting private investment – both domestic and foreign – would help, but it will prove a major challenge in the months ahead. Except for Chinese companies, foreign businesses have so far shied away from investing in any sector outside of mining, where there are tangible assets to back investments.

Test of leadership

There is evidence that without political stability and strong leadership, the economy could lose its edge. The COVID-19 pandemic will be a cruel test for the country’s leaders and its inadequate infrastructure. There are four major warning signs: the decline in the nation’s competitiveness, a growing portion of public expenditure going to personnel, less investment in exploratory mining and a drop in production from the fishing industry, the country’s second-largest industrial activity.

Facts & figures

Since the 1990s, little has been done to strengthen or improve upon the reforms that international financial institutions then imposed on Peru. Worse, two recent corruption scandals in Latin America – Odebrecht and Car Wash – have shown how ineffectual and unaccountable the Peruvian state has become.

Since opposition leader Keiko Fujimori set out to undermine then-President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski a few years ago, the executive and congress have not been able to agree on anything of substance. Ms. Fujimori accomplished her goal with President Kuczynski’s ouster in March 2018. He was replaced by his vice president, Martin Vizcarra, who began his administration with a campaign against corruption. As part of that campaign, Ms. Fujimori herself landed in jail.

That did not help President Vizcarra’s efforts to work with congress. Finally, he dissolved congress on September 30, 2019 and called the people to the polls on January 26, 2020. The newly elected members of congress will sit only until their successors are inaugurated in July 2021. Meanwhile, the congress is fragmented into nine parties. Some of these have agreed to cooperate with the president, who, like Mr. Kuczynski, has a small number of direct supporters holding seats. Even with the parties that have agreed to work with him, President Vizcarra will only barely reach a majority.

The new congress will consider the 62 emergency decrees that Mr. Vizcarra has issued over the past six months. Some of these are of minor consequence, such as the dedication of public funds to the Peruvian film industry. Others, however, hold great significance for governance in Peru: the recomposition of the Electoral Tribunal, reform of the criminal justice system and the return to a bicameral legislature. Meanwhile, the public expects congress to deal with issues like public security, the fight against corruption and improving public education and health services.

China is now the largest investor in Peru’s mining sector and its biggest export market.

While none of the parties has a commanding position in the legislature, it is worth noting the appearance for the first time of Frepap, an evangelical party with a demographic base among the indigenous population in the country’s south. In contrast to the other parties, Frepap is highly cohesive and refuses to cooperate with the executive or with other parties. Similar political groups have appeared in Central America and in Brazil, where they have a major influence on President Jair Bolsonaro’s government.

At the same time, several people have appeared as front-runners in the 2021 presidential elections. While many of them have yet to define their agendas, they offer a variety of positions, from populist to conservative to progressive.

Missing from this group is Veronica Mendoza, who leads left-wing party Nuevo Peru. Ms. Mendoza lost her traction and much of her political influence in October 2019, after partnering with the radical politician Vladimir Cerron.

COVID-19 and China

There are two other considerations that may weigh on the coming campaign. One is that President Vizcarra could influence the proceedings by advancing or blocking judicial proceedings against one candidate or another. Yet he also wants to complete his term in office and protect himself from the kind of postelection persecution that has complicated the lives of his predecessors.

It is impossible to consider the current situation in Peru without mentioning the possible impact of COVID-19. President Vizcarra declared a state of emergency, which will have short- and long-term effects on the country’s supply chains and financial system. Ironically, while informality worked as a buffer against political and social turmoil, it could become a dangerous accelerator for the spread of the virus. Nearly 12 million Peruvians make a living day to day and will be unlikely to obey quarantine regulations for a lengthy period. As of this writing, Peru has reported more cases of the virus than any other country in the region except Brazil. President Vizcarra has called out the military in an attempt to enforce his quarantine.

Facts & figures

Another key factor generating uncertainty is the role that Chinese capital might play. China is now the largest investor in Peru’s mining sector and its biggest export market, passing the United States and Canada, which had held the top two spots for a century. China also plays a key role in the country’s mining infrastructure megaprojects, such as Las Bambas and Toromocho, and is backing a whole host of projects still on the drawing board.

Scenarios

The uncertainty caused by the pandemic complicates forecasting. The most likely scenario for the next few months is that President Vizcarra will move forward with great caution, while demonstrating his determination, even in the face of what might well be a public health catastrophe. The most significant move has been the announcement of an enormous stimulus program, worth $26 billion – about 12 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. Now, distribution of this money will be the key to President Vizcarra’s success or failure.

There are two less likely scenarios. One that we might call optimistic would see the president and his cabinet demonstrate strong leadership, stimulating both public and private sector activity, taking as their model the recovery measures employed in the U.S. and many of the countries in Europe. Argentina, Chile and Colombia have acted in this manner and might serve as models in the region. That would accelerate the process of reform that has been idling since the burst of change in the 1990s.

The other, more pessimistic scenario, would see the government lack leadership. Given the unruly fragmentation of the congress, the central government would prove impotent in the face of the post-pandemic crisis. At the moment, this outcome appears unlikely.