Courage and leadership in short supply

The chaotic exit from Afghanistan, a debt crisis in China and a political mess in Germany all have one thing in common: they were caused by years of poor leadership. As the Western-centric world order winds down, when will governments begin making the difficult decisions?

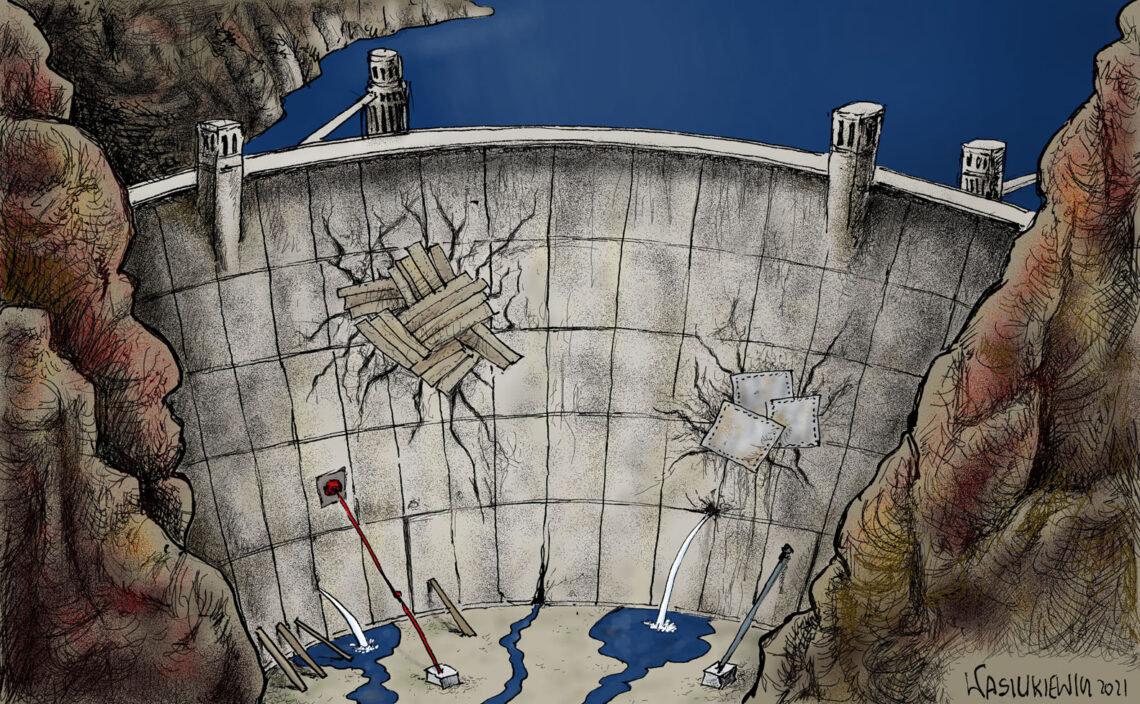

Like a can of worms being opened, events in recent weeks have revealed the consequences of problems that have remained unresolved due to a lack of leadership, courage and statesmanship around the world. We have watched the chaotic exit from Afghanistan, the beginnings of a debt crisis in China with the difficulties of property developer Evergrande, and the messy results of the German elections. Although these three events might appear unrelated, they all came about because difficult issues were not addressed in time. Instead, they were left to fester, papered over and ignored, because their solutions might be unpopular, inopportune or difficult.

As anyone who has a house knows, there are constantly things that require repair – and sometimes you may need to adapt to new situations. Often, such problems can be mitigated in the short term with temporary measures: a new coat of paint, an extension cord, putty to plug a hole, and so on.

Likewise, someone running a company can be complacent for a time, continuing business as usual without being attuned to changing circumstances. You can live through stagnation, creating an illusion of stability. Flaws in the business can be mended through temporary measures like tapping into reserves or taking out a loan. All this is like taking a painkiller to relieve the symptoms of a serious disease rather than undergoing the difficult medical procedure needed to treat it.

Eventually, the dominoes begin to fall. Geopolitically and economically, we have now reached such a moment.

In the above examples, the homeowner or businessperson can be lulled into a false sense of security. Eventually, though, the dominoes begin to fall. Geopolitically and economically, it appears that we have now reached such a moment.

Irresponsible economics

About 10 years ago, Greece’s deep financial troubles kicked off the European sovereign debt crisis. It became clear that governments were growing too big, and that nations’ debts were ballooning out of control. Justified by German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s motto that “if the euro fails, Europe will fail,” huge transfer payments (mainly from northern European countries) stabilized the finances of the countries under duress, institutionalizing the trend toward ever-increasing deficits. Rarely did governments take any steps to reduce public administration or excessive bureaucracy. All this remains a problem today – not just in Europe, but around the globe.

Two “remedies” were implemented to address these issues. The first was to reduce interest rates to zero or even make them negative, which amounted to a hidden tax on savers. The second was for central banks to buy up copious amounts of public debt. That strategy was dubbed “quantitative easing,” but it is really just printing money. These moves encouraged countries everywhere to continue their irresponsible spending policies.

The long-term problem of oversized administrations remained – not just costing money, but also sucking talent from productive parts of the economy in services and manufacturing to the public sector, which was constraining business as it grew. A vicious cycle emerged, in which increasing red tape added to companies’ costs while also limiting innovation and entrepreneurship. As the bureaucratic measures increased, public administration required even more people, further reducing the labor pool for private firms.

The new remedy has been more centralization or the elevation of decision-making to the supranational level.

Recently, the new remedy has been more centralization or the elevation of decision-making to the supranational level, where democratic accountability gets lost.

Other issues that political leaders have left unaddressed include migration and demographic shifts, especially aging populations and the rising pension and healthcare costs that come with them. Energy presents its own challenges: in an effort to transition to a greener future, Germany decided to phase out all of its nuclear power. The result was more coal burning, reduced energy security and the highest energy costs in Europe, jeopardizing the country’s industrial competitiveness.

Tight control

These problems arise in autocratic societies as much as they do in democracies. China, for example, has made huge economic progress since the end of the Mao Zedong era by allowing private property and entrepreneurship. The median income has risen dramatically. But with state-owned enterprises dominating the business landscape and no real capital markets, the Chinese have had difficulty finding places to invest their savings. People began putting money in the residential market, where prices rose almost continually. The government kept blocking the creation of a real capital market to keep tight control over business.

In 2017, President Xi Jinping warned that “houses are for living in, not for speculation,” but his regime provided no alternative. Recently, the government has introduced measures to keep housing prices in check, disrupting the only tenable investment market and setting off the crisis at Evergrande. It is likely that other businesses will follow.

Germany’s mess

In Europe’s largest economy, having the same leadership for 16 years is being credited for having provided “stability” and “predictability.” In truth, stability is being confused with stagnation and predictability with avoiding tough decisions.

Chancellor Merkel has made several choices detrimental to her country in an effort to gain political support. One example was phasing out nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster, a clear ploy to siphon off Green party votes. As she abandoned the Christian Democratic Party’s sound principles, its credibility was eroded, and its voters estranged. It is astonishing that the blame for all this has been heaped on the party and not on the chancellor herself. While party bureaucracy made it difficult for strong personalities to rise up the ranks to challenge Ms. Merkel, she also deliberately marginalized many potential competitors.

The Christian Democrats’ defeat is the result of this mess, created by the policies of the last 16 years.

As the sun sets on her chancellorship, Germany faces several enormous challenges: It could become almost solely liable for all European debt. Its energy market is dirty and expensive. Its business environment is overregulated, holding back entrepreneurship and digitization. Its road, bridge and railway infrastructure is outdated. And its immigration problem remains unresolved. The Christian Democrats’ defeat in last weekend’s elections is the result of this mess, created by the policies of the last 16 years. It is not the fault of Armin Laschet, who led the party’s campaign. Unfortunately, several other countries – both in Europe and further afield – share a malaise similar to Germany’s.

Geopolitical missteps

So far, we have highlighted social and economic issues – but on the geopolitical scene, it is no different. Certainly, the United States-China confrontation is a difficult one to resolve. Over the last 20 years, so-called “convergence theory” allowed for a comfortable complacency. It was taken for granted that rising prosperity in China would result in democracy and the acceptance of Western liberal standards. That idea has been proven wrong.

However, there are also other geopolitical matters which could have been handled much better. For example, Europe and the U.S. have disagreements about trade, foreign affairs and security. For four years, European politicians took the easy way out, blaming Donald Trump for all of the problems instead of addressing these issues head-on and negotiating in good faith.

Instead of crying over spilled milk though, the time has come for difficult decisions.

Another issue is the sanctions imposed on Russia, which have done nothing to resolve the conflict in Ukraine. Meanwhile, Western countries spent 20 years fighting a poorly conceived war in Afghanistan. In Europe, there was little debate about whether entering that conflict even made sense.

There is much talk about preventing mass migration from Africa to Europe. Governments are pumping money into Africa to support such efforts, and organizations hold conference after conference to discuss the problem. But what would a solution really require? Certainly, more efficient border control than European border agency Frontex is now providing. Yet one potential move that is often overlooked could significantly boost African economies and keep people at home: reducing Europe’s protectionist measures and opening up its markets to African products.

Tough choices

The lack of courage and leadership has dire consequences. Democracies are supposed to reinvigorate themselves through political competition and voter engagement. Unfortunately, many political parties are actively hindering democracy’s regenerative qualities. Parties have become a bureaucracy. Once they gain power, most politicians do not independently oversee the administration they are supposed to be governing – they are not serving the people, nor are they leading a dedicated civil service. Instead, they themselves become part of the bureaucratic machine.

On both sides of the Atlantic, we hear lamentation about the end of the “rule-based global order.” Indeed, the world order that was led by Europe and the U.S. has come to an end. Instead of crying over spilled milk though, the time has come for difficult decisions – about how to rein in government, open up economies and think level-headedly about international relations. Doing so, however, will likely be politically unpopular, and today’s global leaders seem not to have the courage or ability to do what is needed.

Unfortunately, it seems there may be more chaos to come. Expect more energy blackouts, further declining internal security and rising inflation before governments decide to rethink the system. Two outcomes are possible. The first is radicalization. The second is a return to more personal responsibility, a leaner state and more subsidiarity. Decentralization would bring decision-making closer to citizens, providing outcomes more likely to meet their needs.