Portugal: The economy is Costa’s next big test

Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa has helped keep populism in check by “taming” radical leftist parties. He has avoided austerity, making him popular and likely to win October’s elections. After that, he will need to solidify recovery in Portugal with deeper economic reforms. The question is whether he can do so with his far-left partners.

In a nutshell

- Prime Minister Costa is popular for avoiding austerity

- He “tamed” populist parties by including them in his coalition

- The economy is recovering but far from healthy

- To tackle Portugal’s structural problems, he needs new partners

Portugal has been praised in European circles as a successful example in containing political radicalism and – among European socialists – as proof that there are alternatives to austerity. As Prime Minister Antonio Costa reaches the end of his first term in office, it is unclear whether his governing coalition, dubbed the “contraption,” remains sustainable. The next big test for the left, however, will not be in the ballots, but on the economic front.

Hard times, clean exit

Since the end of the Estado Novo regime (1933–1974), Portugal has never been a top economic performer, despite its accession to the European Economic Community and the adoption of the single currency. The new millennium has not been auspicious: following seven years of stagnation, a combination of external shocks and internal frailties – weak growth, low productivity and high sovereign debt – submerged the country deep in crisis, forcing Prime Minister Jose Socrates (2005-2011) to request financial support in 2011. While the request was made by a Socialist Party government, the program would be implemented by a center-right coalition led by Pedro Passos Coelho, the leader of the Social Democratic Party (PSD) that won the legislative elections that year.

The government strictly complied with the 78 billion-euro bailout program agreed upon with the “troika” of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The scheme was based on a threefold goal: financial stability, fiscal consolidation through limits on public expenditure, and structural economic reform by liberalizing key sectors. The government found it extremely difficult to find a balance between implementing the program and mitigating its negative effects, especially on low-income groups.

The troika years had a deep impact on the country: company bankruptcies peaked at 41 percent in 2012, while unemployment reached 17.3 percent and the poverty rate rose to 19.5 percent in 2013. Between 2008 and 2016, an estimated 320,000 Portuguese emigrated.

In 2014, Portugal made a ‘clean exit’ from the bailout program. The economy was rebalanced and market confidence restored.

In 2014, Portugal made a “clean exit” from the bailout program. The economy was rebalanced, market confidence restored and access to international capital markets regained. Labor regulations were altered – coming closer to those practiced across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – and the country moved up 25 positions in the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking, from 48th place in 2010 to 23rd in 2016.

The Portuguese exception

The 2015 elections occurred against a backdrop of moderate optimism. While the negative effects of the troika’s decisions still stung, the economy was undoubtedly recovering and there was a general feeling that the worst was over. The coalition “Portugal Ahead” (PaF) led by Prime Minister Passos Coelho, emerged victorious with 38.5 percent of the vote. However, the troika years had reenergized Portugal’s far left, represented by the Left Bloc and the Unitary Democratic Coalition (CDU), led by the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP). These groups – which aggressively opposed the bailout program – managed to capitalize on the discontent of those it affected most. Portugal’s parliament now had a leftist majority.

In a surprising move, Socialist Party leader Antonio Costa declared that he would “bring down the Berlin Wall of Portuguese politics” by establishing a governance agreement with the far left. The agreement, widely known as the “contraption” (geringonca), was negotiated separately between the Socialist Party and each of the other two groups.

While the solution received acclaim internationally, there are reasons to be cautious. For one thing, Portugal has avoided political extremism and populism due to many factors that go beyond Prime Minister Costa’s deal. Moreover, we still do not know whether his solution remains viable or how it will impact the economy.

Economic performance

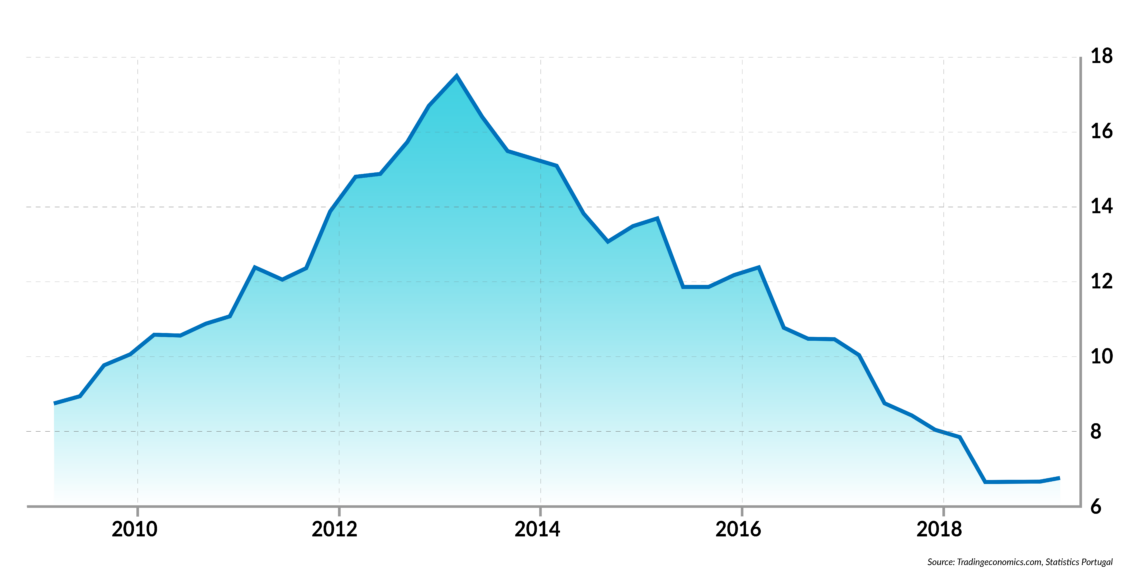

Portugal remained on a path of recovery. The economic reforms were having a positive effect, the global outlook was brightening, exports were rising, internal demand was growing, and tourism was increasing: net exports of travel and transportation services increased from 6 billion euros in 2008 to about 14 billion euros in 2017. The unemployment rate fell by 10 percentage points. The Socialists’ commitment to fiscal credibility paid off, and Portugal managed to overcome a tradition of budget deficits, thanks to the work of Finance Minister and Eurogroup President Mario Centeno.

Facts & figures

Back to work

Portugal's unemployment rate

However, there is still no long-term strategy to overcome Portugal’s big economic challenges. Despite the buzz about how the government ended austerity and how incomes are recovering, perceptions of well-being among the Portuguese remain below precrisis levels. Ironically, in a country where the left – particularly the Communist Party – used to have the unwavering support of the labor movement, this government has faced more strikes than its predecessor. The education and health sectors are struggling, as reflected in the deterioration of key indicators, including infant mortality and maternal mortality. The decline and instability in these sectors hurt a huge swath of the population.

While employment has increased substantially, jobs are predominantly low-skilled, and salaries remain well below the OECD average – a direct consequence of low productivity. Furthermore, moves to make the Portuguese labor market more flexible have created two types of workers: permanent employees, who are highly protected, and temporary workers with no protection at all. This duality compromises productivity gains and discourages investment in temporary workers.

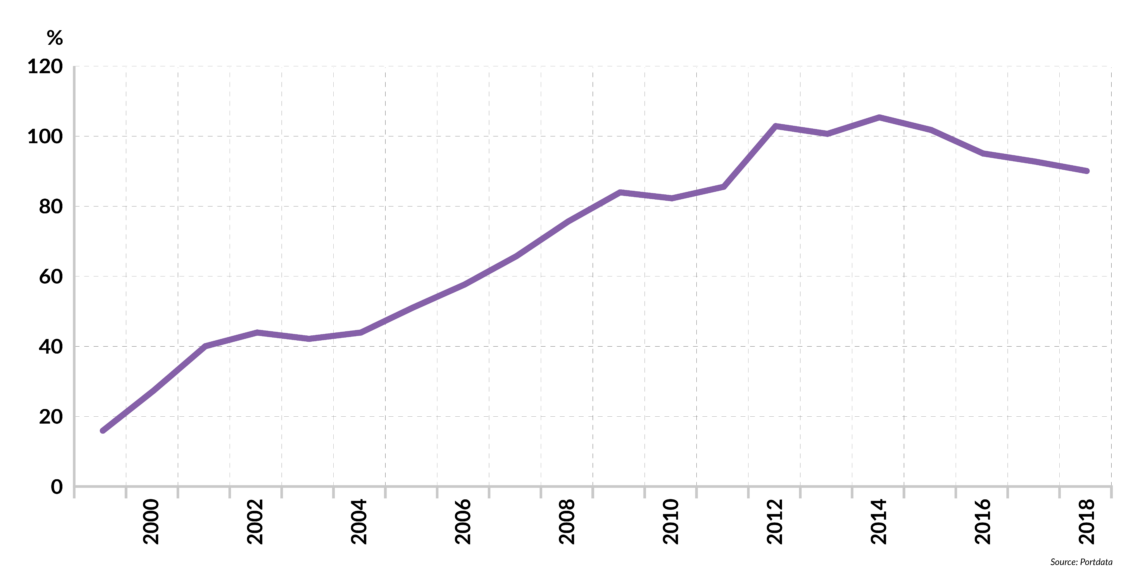

Another problem is the high level of indebtedness within the economy, estimated at 356.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), including high levels of household indebtedness and low saving rates. Portugal’s net external debt hit an estimated at 92.7 percent of GDP in 2018, one of the highest rates in the European Union.

Facts & figures

Heavy burden

Portugal's net external debt, % of GDP

Adding to these structural vulnerabilities, Portugal also faces a daunting demographic change in the coming decades. Its population has been shrinking since 2010 and its birth rate is among the lowest in the EU. The ratio of the elderly to the working-age population – estimated at 35 percent in 2015 – is expected to reach nearly 80 percent by 2075.

Political landscape

Populism on both the right and left has become mainstream in the EU, but Portugal remains the exception. There are two reasons for this. First, migration is not a problem, and there are no threats to national unity or integrity. Second, the only radical parties with political representation are on the left, and they have been “tamed” by Prime Minister Costa’s “contraption” coalition.

Populism has become mainstream in the EU, but Portugal remains the exception.

The results of the European elections seem to validate his solution: the center-right opposition PSD and CDS-PP parties won just 21.9 percent and 6.2 percent of the vote, respectively. Together, the “contraption” parties won 50.1 percent.

Several factors mitigate that success, however. Voter turnout, estimated at less than 31 percent, was among the lowest in the EU. The overall trend throughout the bloc was an increase in participation rates.

Moreover, within the coalition, the CDU garnered just 6.9 percent of the vote while the Left Bloc took 9.8 percent. The result suggests that the “old left,” even with its historical credentials and stable voter base, is being superseded by the “new left.” The Socialist Party won a comfortable 33.4 percent of the vote.

Scenarios

Taking all this into account, it seems likely that Prime Minister Costa and his party will gain the most votes in the October elections. The question, then, is how the economy will evolve and what steps the government will take to address economic developments. There are three broad scenarios to consider.

Controlled deceleration:

Because the Portuguese economy is highly dependent on what happens in Europe, any economic disruption at the European level will hit Portugal hard. In the most likely scenario, demand for Portuguese exports will slow, followed by a deceleration of private consumption, paving the way for a further economic slowdown in the short to medium term.

Economic deterioration could be contained by prudent policies. This will only be possible through a rearrangement of the political landscape: the impossibility of aligning Mario Centeno’s budget discipline with the spending ambitions of the Socialist Party’s partners has become clear, as the latter are increasingly pressured by their constituencies. In this “soft landing” scenario, after the Socialists win the October elections, Prime Minister Costa would focus on economic sustainability and turn his policies toward the political center.

Another crisis

Under a second, somewhat likely scenario, another economic crisis occurs in Portugal. It would be brought on by weak growth, high debt, low productivity and a fragile banking system, all made worse by Europe’s economic deceleration. Several external events could aggravate these factors: Brexit (the United Kingdom is Portugal’s fourth-largest export market), a weakening of the tourism sector, a full-blown trade war between the United States and China, an increase in interest rates, or higher risk perceptions among investors if groups from the far left are included in the next governing coalition.

Convergence with the EU

The possibility that Portugal’s economy will pick up steam and begin to converge with the EU’s is remote, and would depend on two unlikely events: First, the U.S.- and Asian-led global economic expansion would continue, while a rebound in Germany helps stabilize the eurozone economies. Second, Portugal’s government would implement structural economic reforms aimed at stabilizing the banking sector and increasing productivity.

While Portugal’s economy is growing slightly faster than the European average, it is the more developed and robust economies that are bringing that average down. The less advanced economies with similar profiles to Portugal’s (Malta, Ireland, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania and Bulgaria), are growing at faster rates.