Is there a Covid-19 inflation puzzle?

The world’s governments have issued massive waves of debt in response to the pandemic’s economic damage. Public deficits have exploded and central banks are taking extraordinary measures. Will there be inflation or deflation in the post-Covid fiscal future?

In a nutshell

- Central banks have taken unprecedented measures during Covid-19

- A huge demand shock has kept inflation at bay - for the time being

- Debt worries could prompt an inflationary response in the post-Covid fiscal future

In response to the coronavirus outbreak, governments have issued unseen levels of debt to keep businesses and households afloat. As a result, public deficits explode worldwide. Managing them, while at the same time trying to achieve economic growth, could become a delicate balancing act for many states.

For the moment, central banks are supporting governments’ exceptional fiscal measures through no less extraordinary disaster-relief packages. While central bankers, including on the European level, are conducting ever-more ambitious policy experiments, there is one question on the minds of economists: will there be inflation or deflation in the post-Covid future?

Technical wizardry

By law, the European Central Bank (ECB) is not allowed to “monetize” debt, i.e., finance public deficits by purchasing public debt (government bonds) from secondary markets and issuing money.

ECB officials adamantly justify the bank’s first aid measures by pointing to the necessity of countering a drastic and abrupt tightening of financial conditions in the eurozone. At the onset of the pandemic, global financial markets were suddenly subject to dangerous volatility, triggered by massive selloffs. This led to a sharp increase in borrowing costs, exceeding those seen during the 2008 financial crisis – making for a critical situation that, it is argued, called for immediate and aggressive central bank intervention.

On March 18, purportedly in full compliance with its mandate, the ECB launched new broad-based asset purchases at a volume of 750 billion euros of eligible private and public securities. In early June, as credit standards for loans tightened further, the so-called pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP) was increased by 600 billion euros (to a total of 1.35 trillion euros), and its horizon extended to June 2021.

Officials justify the bank’s first aid measures as necessary to counter a tightening of financial conditions.

An additional “temporary envelope” of purchases worth 120 billion euros is set to run until the end of 2020. Moreover, net purchases under the ECB’s regular asset purchase program (APP), which had been reopened in late 2019, will continue at a monthly pace of 20 billion euros, for “as long as necessary.” Finally, the maturing principal payments from securities purchased under PEPP and APP will be reinvested in full, at least until the end of 2022.

Inflation fearmongering

With such formidable and mostly open-ended fiscal support programs, post-Covid fiscal future is unclear and the ECB is navigating uncharted waters. At this rate of money creation, inflation may well be in store, at least if we take textbook economics seriously.

Some economists (who the monetary historian George Selgin wryly labels “inflation mongers”) predict inflation rates of double digits, notably in the United States, for as early as 2022. Among them is business journalist Martin Hutchinson, who recently wrote: “If you think too much money creation causes inflation, we will get inflation. If you think budget deficits cause inflation, we will get inflation. If you are old-fashioned enough to think that rising costs and increasing economic inefficiency cause inflation, we will get inflation. It really does not matter which economic theory you subscribe to, they all arrive at the same destination – more inflation.”

Deflationary tailspin

If all roads lead to inflation, why did the aftermath of the Great Lockdown bring falling commodity prices, tumbling energy prices (by mid-April, some oil prices even went briefly negative), and stagnating wages in hopelessly distressed labor markets?

Although the coronavirus crisis produced an immense negative supply shock (which might have led to a rise in prices), the demand shock turns out to be significantly bigger, driving prices down. Since confinement ended, consumers appear reluctant to catch up with their old spending habits, preferring to continue hoarding as much income as possible. What started as “forced” saving turned into precautionary saving, thereby reinforcing a downward spiral of falling prices.

The fact that central banks are flooding the economy with cheap money does not seem to counteract this tendency for the time being. Cheap credit and emergency grants helped many companies survive during the weeks of hardship. The measures also allowed firms to rush back to conquer frozen markets as soon as the quarantine was over – and to attract the weak demand through further price cuts.

What started as forced saving turned into precautionary saving, reinforcing a downward spiral of prices.

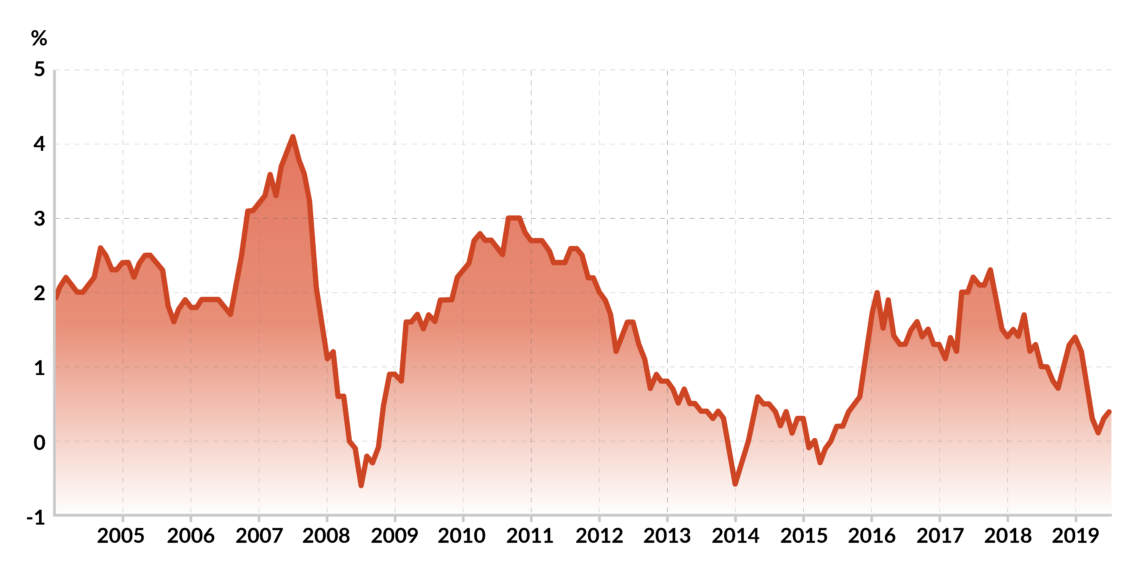

For the moment, all of these factors seem to point to deflationary rather than inflationary pressures. Actual eurozone headline inflation statistics confirm the trend. The so-called Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) has been declining sharply since the outbreak of the pandemic, and in May 2020 fell to 0.1 percent. In the coming months, annual HICP rates could go below zero in eurozone member states badly hit by the coronavirus, such as Spain (-0.3 percent for 2020, per recent estimates).

However, it should be noted that the HICP is a somewhat restrictive indicator of inflation. It does not account for bubbles that can be observed for long on markets, such as stocks or real estate. Real estate prices could continue to shoot up in some economies overheated mainly by the ECB’s ultra-accommodative policy (Luxembourg, among others), thus significantly affecting households’ and businesses’ effective purchase power.

Inflation bets

Another indicator of the current, mainly deflationary trajectory, could be the evolution of demand on inflation-linked bond markets. As recent yield curves for inflation-indexed bonds reveal, investors do not anticipate inflation anytime soon, neither in Europe nor in the United States. For them, nominal bonds constitute a “deflation hedge” rather than an “inflation bet,” as a report by the Centre for Public Policy Research claims. Low inflation expectations, it is argued, reinforce the downward pressure on output, employment and asset prices.

Investors and many economists, including some of the most influential ones, now hold that despite an unprecedented dosage of Quantitative Easing (QE) in the pandemic era, the probability of inflation is minimal in the short- to medium-term. For instance, Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, gives the inflation scenario a chance of less than 3 percent. That probability might even be lower in the eurozone, he adds, given that 19 fiscal authorities who are more divided than ever on solidarity issues can hardly be expected to “get together to impose fiscal dominance on the ECB.”

Easing versus tightening

One of the lessons that policymakers and macroeconomists drew from the 2008 global financial crisis was that, contrary to what textbook economics affirms, QE does not create inflation.

Postcrisis, when central banks started plunging us into a low-for-long interest rate environment, the HICP actually rose, although very modestly. Eventually, QE managed to put a brake on the postcrash deflationary tailspin, preventing us from getting stuck into what economists call a “debt-liquidity trap.” (Even this framing may go too far; in hindsight, experts increasingly think that the deflationary scare might have been exaggerated.)

There is still no consensus among economists as to why, despite more than 2.6 trillion euros of liquidity pumped into the economy between 2015 and 2018, the eurozone’s HICP almost never reached the ECB’s official inflation target of just below two percent.

One explanation is that during the Great Recession, a large part of the funds injected by the ECB vanished in commercial banks. Some observers argue that banks, rather than lending to the economy, preferred using central bank money to shore up their balance sheets, which were encumbered with toxic assets and nonperforming loans (NPLs) after the 2008 crash. This certainly would have contributed to rendering the banking sector safe and sound during recent years, but while keeping much of the needed money from the real economy.

Facts & figures

Could such a scenario happen again in the post-Covid fiscal future? In 2020, banks’ capital and liquidity situations (as well as the quality of their assets) have improved considerably, as European banking authorities are fond of repeating. Moreover, in pandemic times, there are more incentives than ever for banks to grant credit to cash-strained households and businesses. Under the ECB’s recently recalibrated targeted longer-term refinancing operations program (TLTRO III), commercial banks virtually get paid to grant loans, including to the most vulnerable customers.

On top of its generous support for emergency bank lending, the ECB relaxed parts of the constraining EU-banking regulations. For example, capital requirements for market risk have been temporarily lowered, as have the thresholds of customers’ credit risk. Could such measures lead to a new surge in NPLs, thereby creating new incentives for banks to hold back (for their own needs) part of the liquidity freshly injected by the ECB?

As the ECB’s July 2020 euro area bank lending survey (BLS) indicates, banks – obviously deterred by an economic outlook that is going from bad to worse – are increasingly tightening their credit standards for loans to businesses and households.

In the end, it might be banks’ real keenness to lend (and create money), and borrowers’ actual willingness to borrow (and spend money), which will determine the efficiency of TLTRO, PEPP and the other current easing policies. In other words, it all depends on whether market participants will play the game that the ECB wants them to play.

Inflationary, after all?

Importantly, central banks’ expansionary monetary policy is not, as one sometimes reads, a matter of “printing money” out of thin air. In the QE process, money is issued by the central bank in return for less liquid assets: sovereign bonds. Insofar as government debt is supposed to be paid back, there is a wealth counterpart to that money creation.

Thus, at least as long as the “safety” of sovereign debt is not threatened (for example, by fire sales on bond markets in turmoil), there should be no reason to expect skyrocketing inflation.

However, sovereign debt sustainability could become a concern at some point – notably in the euro area, where the specter of a debt crisis is viable for the post-Covid fiscal future as soon as worried investors lose trust in the capacity of overindebted governments to pay back their debt. When markets start to ask for higher risk premia, the debt of concerned governments could become unsustainable. The ECB closely monitors that risk, having experienced that out-of-control yield curves can imperil the entire eurozone.

The specter of a debt crisis is viable for the post-Covid fiscal future if worried investors lose faith in overindebted governments.

To absorb such shocks, some central banks commit to buy the bonds dumped by panicking investors. The ECB is not allowed to adopt such a strategy. However, as Professor Blanchard and his coauthor Jean Pisani-Ferry point out, the institution has made clear that, if rates increase “beyond what is justified by fundamentals,” it stands ready to intervene and buy the bonds that investors are selling off.

Contrary to what one might think, this would not be a hidden form of monetization of sovereign debt, these authors claim. Instead, it would be a sort of low-cost “insurance” against default, provided by the ECB to high-debt countries. Low-debt euro area countries would benefit as well: a European debt crisis and its dangerous cross-border spillovers would not be in their interest, argue the two economists.

However, the ensuing enlargement of the ECB’s mandate could come at the risk of awakening, more effectively than intended, the demon of inflation over a longer horizon.

Puzzle pieces

As pro-stimulus economists insist, deflation appears to be the top threat to our post-pandemic economies. The problem is that deflation increases debt in real terms, making corporate and government debt loads ever harder to sustain. To alleviate the debt burden, the real value of nominal debt has to be decreased. Inflation, then, is certainly an escape route out of a debt deflation-trap – precisely the reason why we could get inflation in the future.

For the moment, the ECB has not shown any inclination to go down that road. But, as Professors Blanchard and Pisani admit, if eurozone governments were to face serious difficulties to repay their corona debt, the ECB “will be bound to choose between inflation, debt restructuring, financial repression and wealth expropriation, and there is no a priori reason to pretend that it must rule out inflation.”

QE is not a free lunch. The British economist Charles Goodhart is right to say that ignoring this fact is “the equivalent to an ostrich putting its head in the sand.”