Covid-19’s long-term geopolitical impact

It is clear now that the Covid-19 crisis will reshape post-pandemic geopolitics. Country size, effective healthcare measures, economic policy and vaccine development are the crucial factors. China is using its early exit from the pandemic’s throes to get ahead of the West.

In a nutshell

- The post-pandemic era of geopolitics leaves little room for multilateralism

- Beijing is using ‘vaccine diplomacy’ to gain an advantage

- The U.S.-China rivalry is bound to heat up even more

It is clear now that the Covid-19 pandemic will persist well into 2021, despite several promising developments toward a vaccine. The longer the virus works its way around the world, the more permanent the changes it has wrought will become. Some long-term effects are already plainly visible.

As long as humanity is battling the coronavirus, density is a vulnerability. Social distancing has forced us to reconfigure our personal and professional lives. Recent headlines herald the demise of the conventional workplace in favor of mobility and flexibility. The phenomenon is mirrored by a sudden skepticism of urban centers and a preference for suburbs and work locations further afield. Many different types of work can now be done virtually, at any time and from anywhere with an internet connection.

In response to the pandemic, politicians have put up unprecedented restrictions on global trade and tourism. With citizens confined to their homes, it has been decades since people traveled so little. On the other hand, states and societies have never had to rely so much on communication technologies – distancing measures have severely reduced in-person interaction.

Larger economies that have virus cases under control may be cushioned by domestic demand and consumption.

Country size will matter in coping with the virus. As relatively autarkic conditions take hold, with receding international trade and investment, larger economies that have virus cases under control – particularly China – may be cushioned by domestic demand and consumption. Their smaller peers that rely on global markets, like Singapore, Switzerland and New Zealand, will find themselves under more pressure.

As infections spike, especially in the United States, India and Brazil, countries are forced to adjust their economic strategy. The changes to the global competition for market share and supply chains will create new winners and losers. Those countries with more effective public health systems will have a better chance at emerging on top, while those with less adequate health infrastructure will face more difficulties. For the first time in generations, health security has become one of the main determinants in the fate of nations.

Facts & figures

Every country will have to fend for itself, as the era of multilateralism wanes in the face of rising nationalism and xenophobia. The trend is led by the U.S., the superpower that designed and underwrote the post-World War II international order. International efforts to fight Covid-19 have been inadequate, so individual states, acting on what they perceive as their best interests, have put up barriers at borders while increasing restrictions on international trade, travel and tourism.

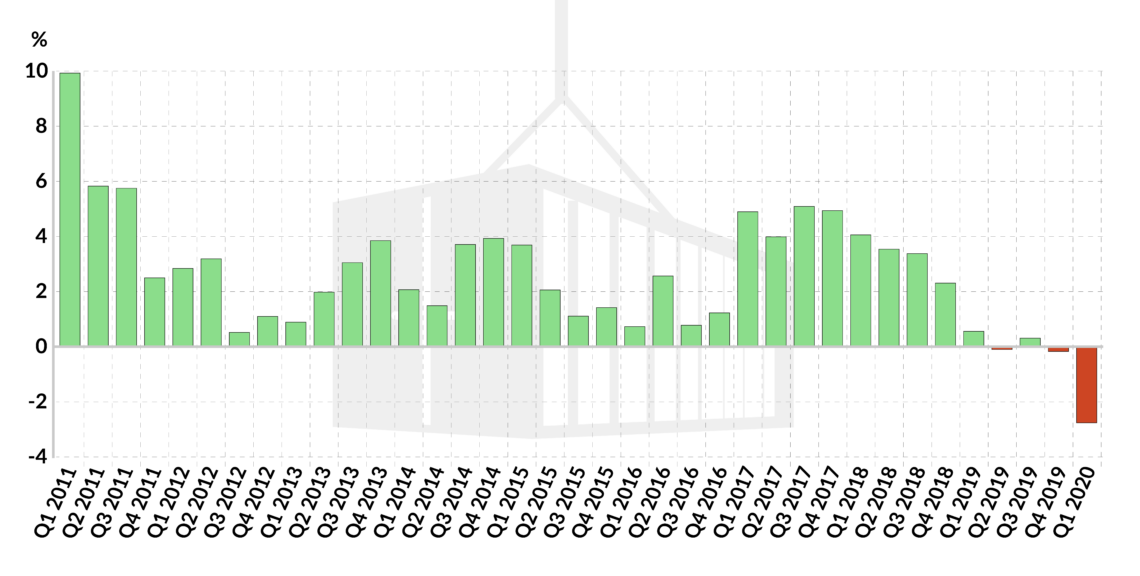

World trade rose from 39 percent of world gross domestic product (GDP) in 1990 to 58 percent in 2018, but this figure is now in steep decline, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). This drop in cross-border commerce has reinforced the fragmentation of the global system. The broad global untangling manifests itself in increased geopolitical tensions, seen in contested arenas such as the South China Sea. These geopolitical trends already portend several global economic developments.

Goldilocks approach

Countries with effective public health systems have stood out. While strategies to deal with the virus have varied, they are correlated with degrees of openness. Countries where outbreaks were contained quickly reopened. This is the case throughout most of Europe and in Asian countries like Taiwan and Singapore.

Thailand and New Zealand, on the other hand, remain closed – caught in a trap of their own making. Having brought the number of daily infections down to single digits or even zero, their populaces have little tolerance for any increase. Both countries have imposed extremely strict quarantine rules that have overburdened the already hurting tourism and hospitality industries.

Other countries have seen runaway infections. The most notable of these include India, Brazil and the U.S. The Worldometer’s coronavirus table of 215 countries and territories says it all, with those worst-hit and most poorly managed at the top.

Countries that find ways to balance both public health and economic goals may emerge from the crisis in the best shape. For instance, Singapore, a small country with more than 57,000 infections but only 27 deaths and with nearly half of its 5.8 million population tested, is as open for business as possible, though with strict hygienic regulations. The Singaporean approach has been to deploy its public health resources to cope with infections while maintaining a robust recovery rate and keeping the death toll down. Over time, the island state is likely to get out of the Covid-19 period in good economic standing and with better prospects for herd immunity.

Vaccine diplomacy

Most countries have now staked their future on a coronavirus vaccine – and the race has become politicized. Russia announced that it had developed one, and is preparing to begin inoculating its population, starting with the front lines of its workforce, like healthcare workers and teachers. Other countries in the vaccine hunt feature China, the U.S. and the United Kingdom. As with initial reactions to the pandemic, major powers are competing even when collaboration would be in their interests. Despite being steadfast allies, the U.S. and the UK are working separately on vaccine development.

In late August Chinese Premier Li Keqiang pledged Beijing would share doses of any vaccine it develops, as well as scientific expertise related to such a vaccine, with Southeast Asian countries. At a recent meeting with his Moroccan counterpart, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi promised his country would offer African countries access to a vaccine. This shows that post-pandemic geopolitics revolve around vaccines as political tools to serve their economic interests.

Post-pandemic geopolitics revolve around vaccines as political tools to serve their economic interests.

Beijing’s vaccine offensive follows its “mask diplomacy” strategy earlier this year: after it brought the pandemic under control within its own borders in March, China offered masks and medical equipment to countries around the world. Now, China’s “vaccine diplomacy” is intended to shore up support for its pre-pandemic undertakings in geopolitics, especially its Belt and Road Initiative, as well as drum up post-pandemic patronage and goodwill to bolster future power projection.

Washington and other major powers may lack the wherewithal to match Beijing’s maneuvers. When the U.S. develops a vaccine, it will likely focus on health recovery efforts at home, where political tensions are running high. The European Union also has its hands full, with member states bickering over internal controls and economic bailouts. Any vaccine from the UK will likely be used in the country and perhaps in the EU before it is made available to other regions. Japan, undergoing a domestic political transfer of power, and South Korea, which must constantly be wary of the threat from North Korea, are too preoccupied to engage in vaccine diplomacy of their own.

This would leave Russia and China to improve their economy and positioning in geopolitics with vaccine development during the post-pandemic era– to the detriment of the West.

Critical mass

Size, regime types and growth models may matter more in global economics than earlier anticipated. Naturally, economies with critical mass and large domestic markets will have an advantage. Yet China’s 1.4 billion population and India’s 1.3 billion people stand in stark contrast to each other. Large markets alone are not sufficient for success without consumer purchasing power and virus containment, not to mention vaccine development.

What stands in China’s way is the U.S.’s entrenched structural dominance.

The Covid-19 outbreak is pivotal because China’s real GDP may surpass that of the U.S. sooner than many had calculated – perhaps even this year. It will be debated fiercely whether China’s single-party-dominant authoritarian political system, with a state-led capitalist economy, is superior to the Western varieties of democratic systems with increasingly stifled market economies. While all economies suffer in varying degrees from the coronavirus pandemic, China’s may end up suffering less and benefiting more after the virus gives way to a vaccine. What stands in China’s way is the U.S.’s entrenched structural dominance, particularly in the resilient role of the dollar as the global reserve currency and English as the globe’s main lingua franca.

Two broad scenarios stem from these trends. In both, the U.S.-China rivalry will intensify. Competition will ratchet up, both for market share and supply chains as well as for allies and partners. In the first scenario, the struggle could head toward open conflict, especially if President Donald Trump is reelected in November 2020.

In the second scenario, the confrontation may not escalate as much if Democratic Party nominee, former Vice President Joe Biden, comes out on top. However, while a Biden-led U.S. administration could temporarily turn down the heat in the superpower rivalry, the outcome – conflict – may be the same.