Post-pandemic social cohesion in the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, as elsewhere, Covid-19 has exposed deep rifts in society and devastated the economy. Yet in post-pandemic times, the UK could come out a tighter knit society than when it went in – if it asked the right questions.

In a nutshell

- Covid-19 exposed and deepened Britain’s divisions

- 2020's challenges include stark economic and racial complications

- The post-pandemic UK can build a narrative around common values

This GIS 2021 Outlook series focuses on the opportunities that stem from the upheaval of the past year.

Britain’s second Elizabethan Age began on February 6, 1952, when the young Princess Elizabeth became Queen of the United Kingdom. During her long reign, she has witnessed momentous political change – including both accession to, and withdrawal from, the European Union; devolution of power within the UK; and the decolonization of vast swathes of a British Empire on which the sun once “never set.”

When at the age of 25 she ascended the throne, Winston Churchill had returned to office as Prime Minister. Since then, she has seen 13 others come and go as occupants of Downing Street. Throughout that time – and even at 94 years of age, in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic – she and the Royal Family have been part of the glue which has held the nation together. But over seven decades she has also seen momentous social change, and not all of it good.

In a speech marking her ruby jubilee in 1992 – a year of family turmoil and one in which she was pelted with eggs in Dresden – Queen Elizabeth described it as an “annus horribilis,” a horrible year. The same could be said for 2020.

National unity in the face of a common enemy – the virus – has been tempered by profound fractures.

1666 was the year commemorated in John Dryden’s poem “Annus Mirabilis” (meaning “Wonderful Year”). It was written in the aftermath of both the Great Fire of London and the Great Plague of London (a useful reminder that pandemics are nothing new). The 17th century poet seemed to suggest that God had ensured that, despite everything, England had come through it all.

Deep divides

But whether England will be able to reflect on 2020 in the same way is very much an open question. As in the horrible year, it has seen its fair share of division.

National unity in the face of a common enemy – the virus – has been tempered by profound fractures that have been exposed to the glaring light. The country remains deeply divided, right down the middle, as to whether it was right to leave or remain in the European Union, and those two polarized positions have redefined the political map, the makeup of the House of Commons, and how communities, families and individuals, see themselves and others. The fractures have exposed divisions of wealth and affluence pitted against disadvantage and disaffection, the socially aspiring and mobile against the trapped and cornered, the metropolitan classes against the rest.

Striding into this already fragmented world came the new Great Plague, Covid-19, with the first UK case recorded on January 31. With over 64,000 deaths in the UK in 2020, the pandemic revealed links between poverty and higher incidences of infection, highlighted disproportionate infection rates among the Black and Asian communities and exposed the consequences of corralling the sick and elderly into accommodation ironically described as care homes.

Will we look back on 2020’s challenges, and the specter of Covid, and say with Dryden that we too came through stronger; that we learned some lessons; and that we made a better attempt (as happened after two world wars) to create a more just and fair society?

Condition of England

The answers will depend on how deeply British people are prepared to look into the fissures and how willing we are to ask searching questions about the condition of the country. In 1839 Thomas Carlyle was faced with the ravages of the industrial revolution. In describing what he observed, he coined the phrase “Condition of England Question,” to shine a light on the conditions of the working classes and the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the newly urbanized.

In his survey, and earlier, in “Signs of the Times” (1829), he wrote about the destruction of human individuality and “mechanization” of the human spirit. He lamented the malign effects of utilitarianism and mere materialism and the effective enslavement of workers. With society “falling to pieces,” he wrote that “a time of unmixed evil” had come, that “private honesty is going” and that “public principle is gone.” But though mired in the Slough of Despond, Carlyle also believed that we might be inspired to work for something better: “the depth of our despair measures what capability and height of claim we have to hope.”

The economic statistics are eyewatering and their social consequences devastating.

His Condition of England Question led to a national debate about the unacceptable poverty of the vast majority, the degree to which it was safe to rely on imports of food and raw materials, whether emigration should be encouraged, the amateurism of the elites and officialdom in governing fairly and competently, and their role in inducing great national misery. Writers, notably Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell (often referred to as Mrs. Gaskell), as well as artists, intellectuals, commentators, religious leaders, social activists and political thinkers began to reimagine the ethos and direction of society and to reset national priorities.

Economic effects

As the wheel of history turns, many of the same vexed questions have once again come to the fore. And as we analyze the contemporary Condition of England Question, politicians wrestle with how best to simultaneously deal with the pandemic and the transitional arrangements and repercussions of exiting the EU, the plundering of the country’s financial reserves to deal with the economic consequences of Covid-19, and the consequences for the rising generation in dealing with an enormous long-term national debt that will threaten their security and prosperity.

The economic statistics are eyewatering and their social consequences potentially devastating. The fall in the UK’s gross domestic product (GDP) during the first half of 2020 represented the biggest drop in three centuries; the country has a GBP 394 billion budget deficit and a staggering national debt – which has risen to GBP 2.1 trillion. The pandemic-induced recession has been worse in the UK than any other G7 state, with disastrous effects for both fiscal policy and employment. There have been 780,000 redundancies since March, accompanied by deepening social disadvantage in the communities that were already most dependent on low wages or benefits.

The pandemic has ushered in an era of big government (paradoxically introduced by a Conservative administration), state spending on a vast scale and terrible social consequences. Data from some studies indicate that in 2020, suicides in the UK may have doubled from the 6,000 that occurred in 2019.

Identity issues

As we draw to the end of this new Elizabethan Age, how we respond to these ruptures and challenges will shape the next chapters of the British story. The outcome will largely depend on how willing we are to read the signs of these times and find new and better ways to respond.

We need to start by moving on from the polarized and toxic debate about Leave or Remain. “Taking back control” may work as a slogan but it does not address the more fundamental questions about who we are as a nation – what the slogan will mean in practice – and whether the breaking of one Union will be followed by the breaking of the United Kingdom itself. Polls suggest that Scotland may seek independence.

Nor does the slogan address the much deeper question about identity: who we are, and how we become more comfortable in our own national skin. Given that immigration and race were significant factors in Brexit, Covid-19 may have inadvertently and helpfully pried open the question of race and migration and, to some extent, detoxified it. I was struck by something the BBC’s Andrew Marr said about this in his new book, Elizabethans: How Modern Britain was Forged.

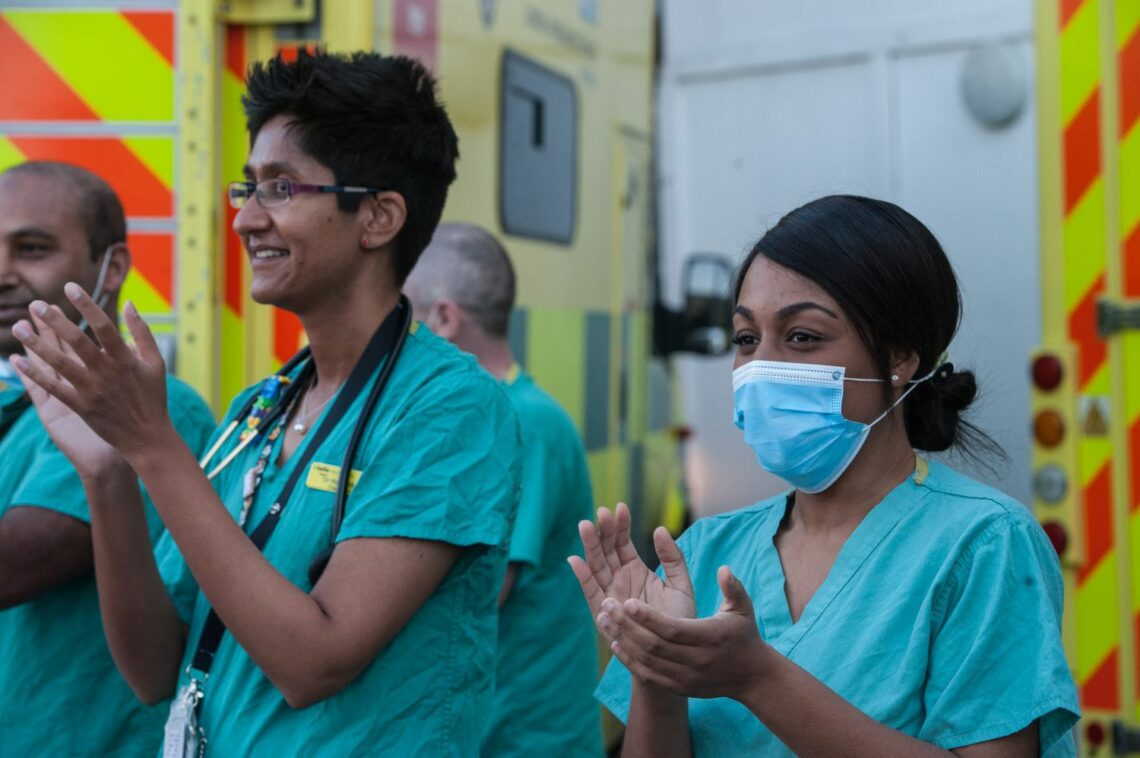

In a remark about the people who have been working in the National Health Service (NHS) to save the lives of those infected with Covid-19, Mr. Marr reflects on the surnames of the first medical workers who died from the disease: Chowdhury, Adedeji, Ayache, Ong, Rathod, Saadu and Tayar. He points out that if this list had been written in 1952 the medics would probably have had names such as Wilkins, Smith, Walker, McDonald, Davies and Jones.

It is the children and grandchildren of migrants who, on arriving in the UK worked long hours in low-paying and often menial jobs, that have been among the doctors and medics who gave their lives to keep open our hospitals and clinics. In 1952, when Queen Elizabeth ascended the throne, Britain had a global story, but it was a story of other places to which Britons went. Britain itself was essentially monochrome.

As few as 20,000 non-White people lived in the UK in 1950, most of whom were born overseas. With the migration that came after World War II, ethnic and racial diversity dramatically changed the face of Britain. But, as the 2018 Windrush scandal illustrated, immigrants have not always been made to feel welcome.

In 1948, some of the first migrants from the Caribbean countries arrived in the UK aboard the Empire Windrush. In 2018 it was discovered that at least 83 of those who had arrived before 1973 were wrongly detained, denied legal rights, and deported – others were threatened with deportation. Some lost their jobs and homes or were denied benefits. But these were not illegal migrants. They were British citizens. Some are from the same families who have powered our NHS response to Covid.

It may be one of the more positive consequences of the pandemic that some of those who have been standing on the doorsteps of their homes, applauding the NHS workers, may have to reassess their attitudes on race. Perhaps fewer people will consider racial minorities a threat and more will see them as a blessing.

Racial challenges

Race and ethnicity are undoubtedly challenges that continue to threaten the social cohesion of Britain but in the face of xenophobic or racist tropes, it is worth reflecting that, although the UK is more diverse, the White population is still a significant majority: 87 percent of the country is White, 6 percent Asian and 3 percent Black, with the remaining 4 percent have other racial backgrounds. Although 37 percent of Britons now say they have no religious faith, 50 percent still describe themselves as Christian, while about 5 percent are Muslim, 1 percent Hindu and 1 percent Sikhs, with a mix of other faiths.

What the pandemic exposed is that in the pockets of the country that have become too ghettoized (towns like Blackburn, which are one-third Asian, or Bradford, which has some electoral divisions that are 70-80 percent Asian) there was a correspondingly high level of Covid-19 transmission. This may be because of cultural factors, high levels of disadvantage, or particular susceptibility to the virus.

The UK needs to construct a narrative around common values and citizenship.

Poorer White people have also been disproportionately affected by the virus and the fear must surely be that these communities will take longer to recover. Especially with the negative effect of Covid-19 in disrupting education, societal disadvantage may be transmitted into the next generations.

Anxiety about the challenge to social cohesion posed by inadequate assimilation is quite widespread in the UK, with fears that the state would be unable to absorb more immigrants, that the state’s architecture of schools, hospitals, welfare and so on, will cease to function if ever-increasing demands are made upon it. Overlaying these anxieties is the threat from radical Islamists who are prepared to use violence and terror to change a country’s beliefs or way of life.

Beyond a commonly held belief in the NHS – which sometimes assumes the status of a national religion – the country does have an identity problem. It needs to work out why some people think they belong and others do not, and construct a narrative around common values. We know now that the virus did not discriminate. Moreover, just as families needed one another, we need a functioning state accountable to Parliament – and all Britons have a part in making it function. These realizations may just bind the nation more closely together.

Pleasant surprises

As we draw closer to the end of the Elizabethan Age, we can say that there is a lot on the credit side of the balance sheet. We are a less class-ridden country and have become more of an American meritocracy where your birth need not define all your expectations of life. Blessed also with the near-universal English language, the opportunities for using the Queen’s English may help to reset the UK’s economy, trade, commerce and its interaction with the rest of the world – especially in vast swathes of the globe where English is the predominant language.

And, post-Covid, the contemporary Condition of England Question may also reveal a few other pleasant surprises. Throughout the pandemic, it has been revealing to see the genuine attempts by families to look after one another and especially elderly relatives. It may lead to the realization that institutionalizing the aged and infirm in homes for the elderly does not necessarily represent the best care we can provide.

The average age of coronavirus fatalities has been 82 years old (one year above the average life expectancy in the UK). But the places where they have died in great numbers have been the aforementioned inaptly named care homes. As our population continues to age (around one in five are over 65) and the birth rate hovers at only 11 births per 1,000 population, the Baby Boomers born when Queen Elizabeth came to the throne may now reimagine the way they expect to be cared for.

My sense is that Covid-19 has strengthened rather than weakened families – and not just concern for elderly members. Homeschooling has forced some parents to have more than a passing interest in their children’s education. Einstein said that if you want your child to be a genius, read to them. Many more parents have been picking up books and reading to their locked down children.

Counting blessings

Zoom calls have reunited families across long distances. I recently took part in a call with 17 of my cousins – some of whom I had not seen for years. Such interaction may become a permanent good, although I cannot be alone in hoping that interaction in person, rather than merely through a computer screen, will again be our preferred way of living.

In our universities, it may be easier to give a lecture or tutorial online – and from time to time this has its place – but I wonder how I would have coped as a first-year student in Liverpool if I had been told I could not leave my residence hall and had to study via endless Zoom sessions. When university authorities in Manchester put up metal fences around one such hall to stop anyone from getting out, I raised a cheer of approval for the students who pulled down this cage.

Social distancing – as distinct from locking people up – has drawn people back into the beautiful British countryside, and given them a new appreciation of its wonder and the enjoyment of rambling, walking and cycling rather than living the life of a couch potato. By comparison, overseas flights and foreign tourism have been eviscerated. Good for the environment, some will say, but surely bad for our global connectedness.

The pandemic has allowed government to stampede new laws through Parliament.

Covid-19 has made most people more considerate of others, but some have displayed complete indifference. It has allowed government to stampede new laws through Parliament, rushed through with stealth, taking powers usually associated with totalitarian regimes and which include gross intrusions on personal freedoms. But, equally, it has made us more vocal in insisting that any setting aside of human rights for the common good must be short-lived.

Still, the temporary can so easily morph into the permanent. That goes for laws and the effects on our high streets and local community shops. Lockdowns have had a disastrous effect on the hospitality sector, recreation and leisure facilities, and smaller shops and high streets. Amazon has been notching up whopping profits, along with other internet-based outlets, but as online retailing becomes normative, will we really be content to see our town’s high streets, neighborhood shops, local pubs and restaurants all become fatalities of Covid-19?

Post-pandemic UK

Above all, the pandemic may have forced us to count our blessings anew. Economic contraction and social challenges will be painful in the UK, but imagine the impact on a struggling family in sub-Saharan Africa doubly, hit by our decreased ability to fund development. Imagine coping with Covid-19 if you are one of the 70 million people who are refugees or displaced by wars and persecution – numbers that have increased as warlords have exploited the cover of Covid.

Imagine that the clock turned back to John Dryden’s Great Plague of London. Up to 100,000 died in London alone, a quarter of its population. The Yersinia pestis bacterium, the bubonic plague, swept through the homes of Londoners, just as it had 300 years earlier, when the Black Death took the lives of 25 million Europeans. Imagine that, and how we would have fared in the absence of brilliant scientists and lifesaving vaccines and in the absence of the NHS and modern medicine.

Like Dryden, that alone should make us count our blessings – and ensure that when the post-Elizabethan Age arrives, that we are better prepared when the next virus is inevitably unleashed upon us.