Xi’s growing influence goes beyond constitutional changes

China’s National People’s Congress recently abolished term and age limits for the highest offices, including that of the president. While the changes may not mean much for the workings of the Chinese party-state or the country’s development, they are part of a broader effort by President Jinping to expand his and Communist Party influence.

In a nutshell

- China’s legislature recently abolished term and age limits for the highest offices

- The amendments are part of a broader effort to expand President Xi’s influence

- Other, less noticeable moves are consolidating power in the Communist Party

- Despite the changes, China’s direction and development will largely be unaffected

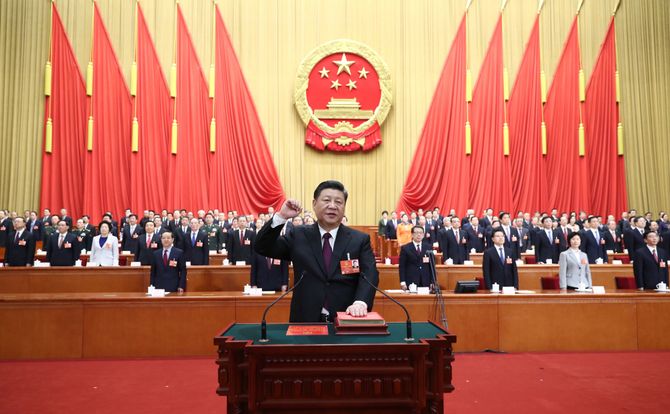

China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress, made several amendments to the constitution at its March session, including one that abolished term limits for the presidency.

While it attracted the most international attention, the change was not very significant according to the letter of the law. The office of the president carries certain symbolic powers. The president engages in the state’s affairs and receives foreign representatives, appoints ambassadors and ratifies and abrogates treaties.

Extending these powers beyond the two-term limit does not by itself bestow much additional influence. Even the president’s power to nominate the premier is, in fact, co-opted by the Politburo Standing Committee.

The post of president, which in Chinese still translates as “chairman,” has existed for much of the country’s postrevolutionary history. Although it was never irrelevant, it has been occupied by those ranking third or even fifth in the party-state hierarchy of power. The party’s secretary general has only been performing the duties of the president since 1993.

Meanwhile, the most powerful position – the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) – had not been restricted to two-terms by the party constitution before the recent legislative session, and it still is not. To what extent does scrapping term limits really enhance the powers of President Xi Jinping? When all the developments of the last year are viewed together, the significance of the change becomes more obvious.

Facts & figures

Key figures in China's government

- Xi Jinping: 65 years old. President, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, General Secretary of the Politburo Standing Committee

- Li Keqiang: 63 years old. Premier, member of the Politburo Standing Committee

- Wang Qishan: 70 years old. Vice President

- Li Zhanshu: 67 years old. Chairman of the National People’s Congress, member of the Politburo Standing Committee

- Wang Huning: 62 years old. First-ranked secretary of the Secretariat of the Communist Party of China, member of the Politburo Standing Committee

- Zhao Leji: 61 years old. Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, member of the Politburo Standing Committee

- Yang Xiaodu: 64 years old. Director of the National Supervisory Commission, member of the Politburo

- Liu He: 66 years old. Vice Premier, Director of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, member of the Politburo

By the book

For the last two decades, the CPC and the state apparatus were governed by two strict rules, among others. The first provided that no one above the age of 68 could be appointed to any position, even at the highest levels.

As a result, those who reached the pinnacle of power (such as the offices of general secretary, premier or the member of the Politburo Standing Committee) were generally under 68 years old. Those who were likely to serve two terms were much younger than 63 years old at the time of the first term, as was Mr. Xi himself when he was appointed general secretary in 2012. Lower age limits apply to lower-level positions. It is worth noting that the age limit of 68 was arrived at opportunistically after power struggles during the late 1990s, when certain factions tried to out-maneuver others in appointing the highest officials.

China’s seemingly rigid bureaucracy and ideology can disguise an innovative, flexible and modern system.

The second rule was that anyone, even at the highest levels, could only serve in a given position for two consecutive five-year terms. These rules applied quite universally and were inscribed into the constitution in 1982 for the office of president and, later, for other positions. While the party constitution does not include term limits, the party-state is a unified entity in China and it was understood that the rule applied to the party as well.

These two rules, combined with meritocratic recruitment and promotion policies, shaped the country’s modern party-state system, which is idiosyncratic. Some of these features resemble those in Japan and Singapore, while some are distinctively Chinese and derive from its communist and Confucian past.

China’s seemingly rigid bureaucracy and ideology can disguise a system that, when needed, has proven to be innovative, flexible and modern. In addition to the overall commitment of the party-state leadership and the establishment of pro-market reform, one can argue the meritocratic bureaucracy – and the rules that enabled it – have been a cornerstone for the success of the last four decades.

Changing the rules

For the moment, the two-term limit has been abolished only for the positions of president and vice president. Seemingly of equal importance, the age limits have also been revoked for these two offices.

Wang Qishan, who was appointed vice president in March, was 69 years old at the time of appointment. He is Mr. Xi’s most trusted associate and oversaw the country’s drastic anti-corruption campaign, which rid the field of many political competitors while simultaneously combating graft. Mr. Wang, regarded as a skilled manager and a pro-reform politician, was important enough to be elevated to the position of vice president despite his age. But more important than his personal promotion is that the age restriction for the job was disregarded.

All other constitutionally mandated positions are still bound by term limits, and, judging by other appointments at the highest levels, their age restrictions were also maintained. For instance, Li Zhanshu was a few months shy of 68 when he was appointed chairman of the National People’s Congress. There were no reports for any other appointments above the age of 68.

Because the age and term limits have been maintained for all other positions in the party-state, one should not overstate the significance of the recent changes for the overall system. The likelihood of China being ruled by a gerontocracy in the style of the 1980s Kremlin is low, at least for the foreseeable future. As long as the robust meritocratic system survives throughout the party-state bureaucracy, with regular personnel shuffles and upward mobility, the prowess of the current Chinese state is likely to persist.

Consolidating authority

For President Xi, the removal of term limits does not much enhance his institutional powers, which are already huge. However, it does pave the way for possible future terms as party-state leader while maintaining the key norms of China’s governing system. Instead, other changes to the constitution – as well as nonconstitutional changes – have increased Mr. Xi’s sway.

Many observers noted the establishment of the National Supervisory Commission (NSC), a new anti-corruption agency, as a significant boost for Mr. Xi’s influence. However, such a system was already in operation. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) had been the party’s arm of control, firmly in the hands of Mr. Wang, the Xi ally who is now vice president. It has waged an unprecedented campaign on graft over the last five years by disciplining 1.5 million officials, including some at the highest echelons of power, such as the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC).

The major difference between the CCDI and the new NSC appears to be the latter’s broadened scope, as its operations will cover not only members of the party but nonmembers as well. The body will also unify all anti-corruption agencies previously under different umbrellas.

Like the CCDI before it, the NSC can detain, wiretap, interrogate and perform other extensive powers against officials suspected of bribery. Much has been said of the denial of access to lawyers, but this too was a practice under the CCDI. The major difference now is that the new body is not a party organ but a state agency, with its powers legislated by law rather than in party documents. That distinction had created legal gray areas for the CCDI’s activities, whereas the NSC can now presumably operate with clearer legality.

From now on, the Communist Party will be firmly in charge of all anti-graft operations.

Politically, and more significantly for Mr. Xi, the change removes all anti-graft authority from the cabinet, headed by Premier Li Keqiang. For now, the NSC will be co-located with the CCDI, and its chief, Yang Xiaodu, will continue to act as deputy to CCDI head Zhao Leji. Mr. Zhao is also a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, placing him one rank higher than Mr. Yang, who is a member of the extended Political Bureau.

This keeps the primacy of the CCDI over the NSC, at least for the moment. In any case, the party will be firmly in charge of all anti-graft operations from now on, and the cabinet will have very little power in this area.

Small groups getting bigger

Another move was not enshrined in the constitution, but it was crucial for China’s governance: the elevation of the party’s four so-called “leading small groups,” which are focused on economy, reforms, foreign affairs and cybersecurity. In a rather obscure bureaucratic maneuver, the four small groups will be upgraded into commissions, increasing the power of President Xi at the expense of the cabinet.

For instance, the two groups central to economic decision-making – one responsible for deepening overall reforms and the other for financial and economic affairs – already had an outsize influence, and the change seems to only increase their formal powers. Both remain headed by Mr. Xi. However, Premier Li now appears to be the deputy of the economic commission, while two members of the Politburo Standing Committee reportedly serve as deputies of the reforms commission.

At its last meeting, on July 7, 2018, the reforms commission approved a wide range of documents, which included support for the Xiongan New Area in the northern Hebei province and a plan to set up a new public interest prosecution division . Judging from the list of the documents approved, the powers of the commission are extremely broad. Conspicuously, Premier Li was not reported to be its deputy nor was he reported present at the meeting. This is most likely not a coincidence.

Elevating the two groups to the status of commissions increases President Xi’s influence over economic matters.

More importantly, Liu He – a member of the Politburo, a vice premier and reportedly a close confidant of Mr. Xi on economic matters – was serving as director of the office of the leading group on economic affairs and is likely to remain in charge of the new commission’s secretariat. Likewise, the new commission on deepening reforms is headed by Wang Huning, a Politburo Standing Committee member, first-ranked secretary of the party’s Secretariat, and another close ally of Mr. Xi.

The elevation of the two groups to the status of commissions and the concentration of their work in the hands of Mr. Xi’s allies have likely further cut off the powers of Mr. Li and the cabinet and increased Mr. Xi’s already overwhelming influence over economic matters.

A steady course

The changing landscape of Chinese politics does not, by itself, say much about the future direction of the country. The curtailed powers of Premier Li and the extended powers of the party under President Xi are neither inherently good or bad developments. What matters is that all of the factions and groups within China’s elites seem to be firmly behind the market and reform agenda. Their shifting influences do not change the profound direction of China’s development, as happened, for example, after the death of Mao Zedong.

Most importantly, the current system of governance is still operating: a meritocratic selection and promotion of party-state apparatchiks based on selecting the best and brightest university students, especially at the entry level, combined with regular reshuffling and term/age limits. These are the key features of the modern Chinese party-state, enabling a relatively free inner debate on economic issues, experimentation, and science- and knowledge-based public policy.

If those features retreat, then observers must begin to have more profound concerns about the direction of China. All other changes are distinct aspects of the Chinese model of development, from the incorporation of “Xi Jinping Thought” into the constitution to the inclusion of the Communist Party leadership as a fundamental feature. So far, despite all its idiosyncrasies, that model has delivered results.