African countries move toward fiscal consolidation

Stung by falling commodities prices and growing donor fatigue, many African countries are expanding their tax bases. While at first blush this looks like a good move to liberate their economies from aid and resource dependence, it could also be a recipe for reducing investment and tamping down economic growth.

In a nutshell

- African states derive little revenue from taxes, relative to the rest of the world

- Aid inflows are dwindling, while prices of commodity exports have dropped

- Some countries on the continent are making up for this by raising taxes

- Only those that maintain favorable business conditions will be successful

African economies have extremely narrow tax bases, particularly when compared with the rich economies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These reflect the continent’s low economic diversification, the excessive weight of the informal sector, as well as weak governance and regulation.

In recent years, the collapse of global commodity prices, shifts in trade and donor fatigue have led several African countries to reform their tax systems to increase and diversify revenue. By providing a stable, predictable funding for public investments and social services, broader tax bases could help liberate African countries from aid and resource rents in the long run. However, they could also compromise much-needed investment and economic growth.

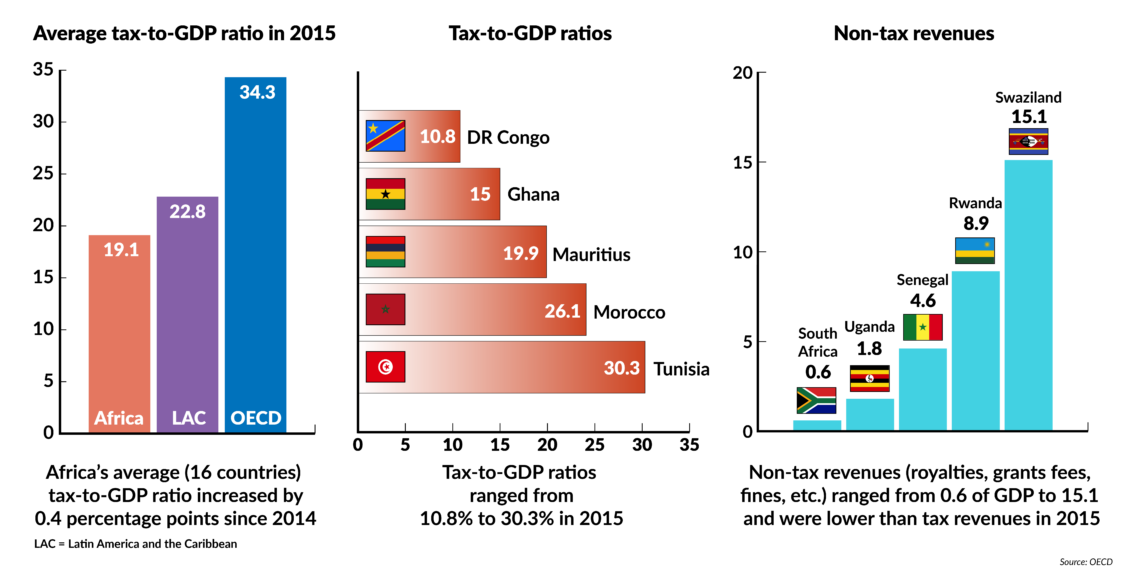

According to the 2017 Revenue Statistics in Africa, a joint publication by the OECD, the African Union Commission and the African Tax Administration Forum, the average ratio of tax to gross domestic product (GDP) in 16 countries representing the “African average” was 19.1 percent. This figure is well below those for Latin America and the Caribbean (22.8 percent) and the OECD (34.3 percent).

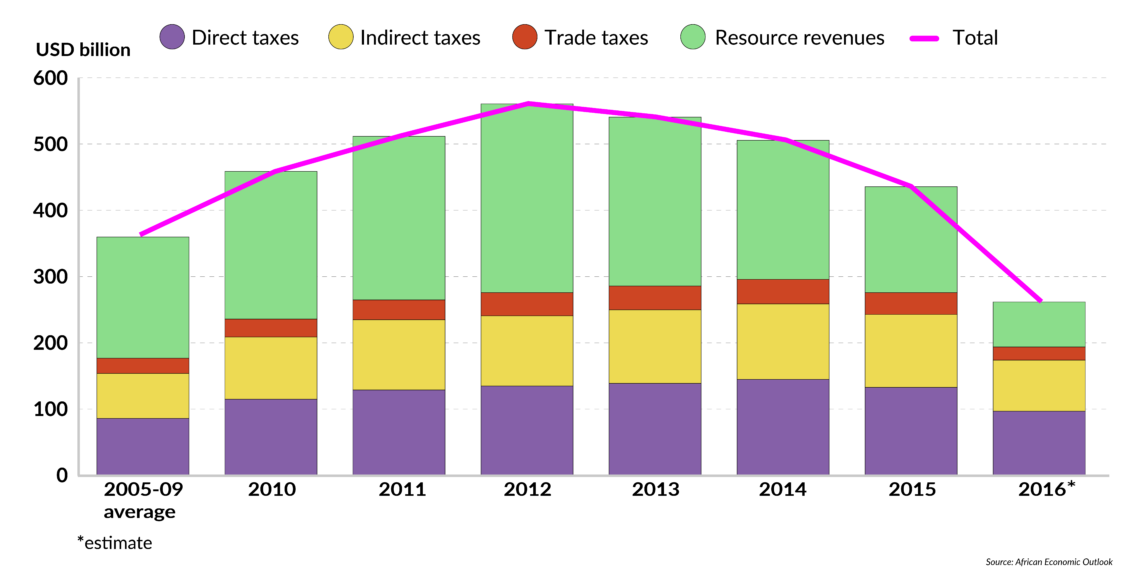

In some African countries, taxation of resources is a big and often volatile share of tax revenue.

Tax-to-GDP ratios range from 10.8 percent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to 30.3 percent in Tunisia. Besides Tunisia, the highest tax-to-GDP ratios are in Algeria, Seychelles, South Africa, Botswana, Morocco and Namibia, suggesting a link between taxes and economic development.

Taxes on goods and services – notably value-added tax (VAT) – account for the biggest share of tax revenue in most African countries (57.2 percent on average, according to OECD data). In some countries, including several of Africa’s biggest economies, like Angola and Nigeria, taxation of resources represents a big – and often volatile – share of tax revenue. As for non-resource rich countries, according to the 2017 African Economic Outlook, “reformist” countries like Ethiopia, Rwanda, Togo, Swaziland, Malawi and Seychelles have significantly expanded domestic revenue mobilization through increases in both direct and indirect taxes.

Economies and political environments

Low prices have reduced the role of resources and primary commodities in driving growth. This has changed Africa’s economic outlook, as reformer economies are now outperforming resource-rich ones. According to the 2017 African Economic Outlook, between 2012 and 2015, resource revenue fell by more than 50 percent in Algeria (51.8 percent), Angola (57.2 percent), Chad (65 percent) and Gabon (55 percent). Growth is now led by non-resource intensive economies such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, Senegal and Cote D’Ivoire. As traditional sources of funding, like development aid, rents and royalties from resources and taxes on trade – become less available and more volatile, some African governments have prioritized fiscal policy consolidation to boost state income.

However, taxation is intimately connected to political circumstances. In modern democracies, fiscal policies are part of the social contract between citizens and the state, which is based on mutual trust. Besides economic considerations, political legitimacy and accountability are also crucial. So-called “tax morale” – the citizenry’s motivation to pay taxes – will be lower in regimes perceived as corrupt, illegitimate or unable to provide basic services and infrastructure.

This question is particularly relevant in Africa, where political constraints remain a major obstacle to growth and development. In contexts of state fragility – marked by instability, insecurity or conflict – the state lacks both the capacity and legitimacy to collect income or property taxes, compromising the country’s domestic revenue potential.

Challenges, risks and opportunities

To step away from aid and resource dependence, African countries will have to increase their domestic revenue. However, some fiscal strategies may scare away potential investors, while a combination of high taxes and bad governance will hamper the expansion of Africa’s (still incipient) middle classes. South Africa, for example, has high corporate taxes and one of the most progressive tax systems in the world. Yet inequality levels remain high, and the quality of public health, security and education services remains low. Consequently, the emerging middle class is effectively double-taxed, having to pay privately for services that should be covered by their taxes but which the state cannot deliver.

Facts & figures

The tax revenue mix in Africa, 2005-2016

Another challenge for fiscal consolidation is the weight of the informal economy in many African countries. According to the 2017 African Economic Outlook, the average size of the informal sector in sub-Saharan Africa represents 38 percent of the region’s GDP. Youth unemployment, low employment rates among women, high levels of unpaid domestic work and high fertility rates often contribute to high dependency ratios in African countries; often several individuals depend on each wage earner, squeezing the tax base and compromising tax revenues. In some African countries where ethnic affiliation or regional identities are important for determining resource distribution, such as Kenya, Sudan and Nigeria, fiscal centralization may undermine tax morale.

Despite the challenges, there are success stories. Rwanda, for example, managed to increase revenues by nearly 50 percent between 2001 and 2013 through sound reforms. Equally important, the Rwandan government was able to decrease aid dependency in key sectors, such as health, by efficiently using tax revenues. In Nigeria – an economic and demographic giant with 200 million people – only one-fifth of the country’s 70 million active citizens pay taxes. Faced with extremely high levels of corruption and plummeting oil prices, the Nigerian government recently announced its new National Tax Policy, which includes a voluntary asset and income declaration scheme to recover missing tax revenues and expand the country’s tax base. The government expects to raise $1 billion from past missed tax revenues, though that figure may be too optimistic. The new policy also includes a lower tax rate and VAT compliance threshold for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

While companies in the formal sector are subject to high corporate tax rates in Africa (29 percent on average), activities in the continent’s cash-led informal sector – which accounts for a large share of the GDP in countries like Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique – often evade taxation. If reforms to regulate the informal sector succeed, tax bases could be broadened without compromising growth.

Countries with adequate business environments are in a better position to reduce the size of the informal sector by providing opportunities for SMEs to thrive. In countries where business activities are mostly concentrated in large enterprises (be they state-owned, partly state-owned or multinationals) and informal entrepreneurs, widening the tax base will likely prove more difficult.

Illicit trade in sub-Saharan Africa accounted for between 7.5 and 11.6% of total trade from 2005 to 2014.

Another opportunity to increase tax revenues without hampering growth – which the Nigerian and Angolan governments seem to be grasping – is to implement more effective control mechanisms to stem illicit trade flows. Washington, D.C.-based advisory Global Financial Integrity estimates that the volume of illicit trade flows in sub-Saharan Africa accounted for between 7.5 and 11.6 percent of total trade on average between 2005 and 2014.

Adapting to demographic shifts

A crucial factor for the success of fiscal consolidation in Africa is the capacity of governments to adapt to demographic shifts.

Africa has the world’s highest rate of urbanization, which means that to avoid widespread urban poverty, governments will have to raise public expenditure on basic services and infrastructure in urban areas. Property taxes may therefore increase in some of the continent’s “megacities,” including Dar es Salaam, Lagos, Kinshasa and Addis Ababa. However, the centralized collection of property taxes and the immaturity of real estate markets could compromise the revenue gain in some countries.

Africa has an extremely young and rapidly growing population, and life expectancy is expected to increase throughout the next decades. These demographic trends can represent a threat or an opportunity, depending on economic and political conditions.

Africa’s middle class – estimated at 500 million by the African Development Bank in 2012 – remains incipient and fragile. The reference threshold adopted was individuals who live on $2 per day, reflecting low, volatile incomes – a large portion of the middle class works in the informal sector. As Africa’s middle class strengthens, it could significantly change the continent’s economic and political prospects, driving growth through consumption and domestic demand and significantly widening the tax base. However, this will depend on the political and economic context in each country.

But while that outcome remains uncertain, at least in the medium term, the increase of life expectancy at birth is now a reality in many African countries. This poses a major challenge for governments, as only a small portion of the working population is covered by pension insurance under public or private schemes. According to the International Labour Organization, only 8.4 percent of the sub-Saharan African workforce contributes to pension insurance. The situation is further aggravated by the erosion of informal systems of social protection that comes with rapid urbanization and cultural changes.

Scenarios

Fiscal consolidation will remain a priority for most African countries, reflecting the effects of the slump in commodity prices and declining levels of official development assistance (according to the 2017 African Economic Outlook, the share of aid allocated to 17 of Africa’s 27 low-income countries is expected to decline until at least 2019). While stable African countries will likely continue to prioritize fiscal reforms, unstable countries are expected to lag.

Political stability and sound business environments will be key for fiscal consolidation to succeed in sub-Saharan Africa. Considering the high level of political and economic risk in many African countries (including poor business environments, weak property rights, unreliable access to electricity, as well as low accountability and transparency), tax hikes – especially for corporations – could deter investors.

Some countries will be able to shore up revenues by broadening the tax base without sacrificing economic growth. These will be better able to wean themselves off aid and adapt to major demographic shifts. This will require a delicate balance between state policies and market forces. Strong, albeit market-friendly, regimes in countries like Ethiopia, Rwanda, Morocco and possibly Angola may be better positioned to face the upcoming challenges. Efforts to regulate the informal sector, for example, tend to create significant resistance and may lead to periods of social unrest, as seen in Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Demographics will also matter. High dependency ratios will likely have a negative impact on tax revenues (narrowing tax bases and potentially increasing tax rates) while requiring higher government spending. Countries with strong or emerging manufacturing sectors – as in Algeria, Morocco, South Africa, Ethiopia or Senegal – are in an advantageous position, because their citizens have better employment prospects and more reliable incomes.

The share of elderly in the African population is expected to increase over the next few decades, making the creation of efficient social security systems a serious challenge for governments. Declining fertility rates and the increased participation of women in the labor market should lower dependency ratios in countries such as Mauritius, Seychelles, Cape Verde, South Africa and Rwanda.