Restarting economies: Benefits of the bottom-up approach

Generally, there are two ways of restarting economies: top-down and bottom-up. The latter dulls innovativeness while the former reinvigorates businesses and makes them more agile, allowing them to make decisions and take risks independently.

In a nutshell

- Top-down restart initiatives for the economy push out private investment

- Bottom-up restart initiatives reinvigorate businesses and innovation

- Allowing businesses to decide for themselves creates much-needed variation

Shutting down an economy is easy to do. Depending on the legal system, it typically only needs an executive or legislative order. Restarting, on the other hand, is a complex and lengthy procedure.

In the first half of 2020, as a measure to mitigate the spread of Covid-19, many countries severely restricted economic activity. China implemented what some have dubbed the largest quarantine in human history. Italy followed that example. Germany, France and Spain did not allow retail outlets, restaurants and similar businesses to operate, urging their citizens to stay at home. Switzerland, despite its long tradition of direct democracy, even partially locked down its economy without taking a popular vote to validate the measure.

Once such measures are taken, the question becomes how to manage the restart of the economy. The various ways countries opened back up the economy shows that bottom-up restart approaches work better than top-down ones.

Facts & figures

Kurzarbeit

Kurzarbeit or “short work” is a social insurance program adopted by German-speaking countries to protect workers’ jobs and income. Under Kurzarbeit, employers reduce the hours their employees work, but do not fire them. Then, the government provides an income “replacement rate,” which in Germany, for example, equals 60 percent. Workers therefore receive full pay for the hours they work, and 60 percent of their pay for the hours they do not. A 30 percent reduction in hours, for example, would result in only a 10 percent loss in salary. In Germany, the program usually runs for a maximum of six months.

Value creation, interrupted

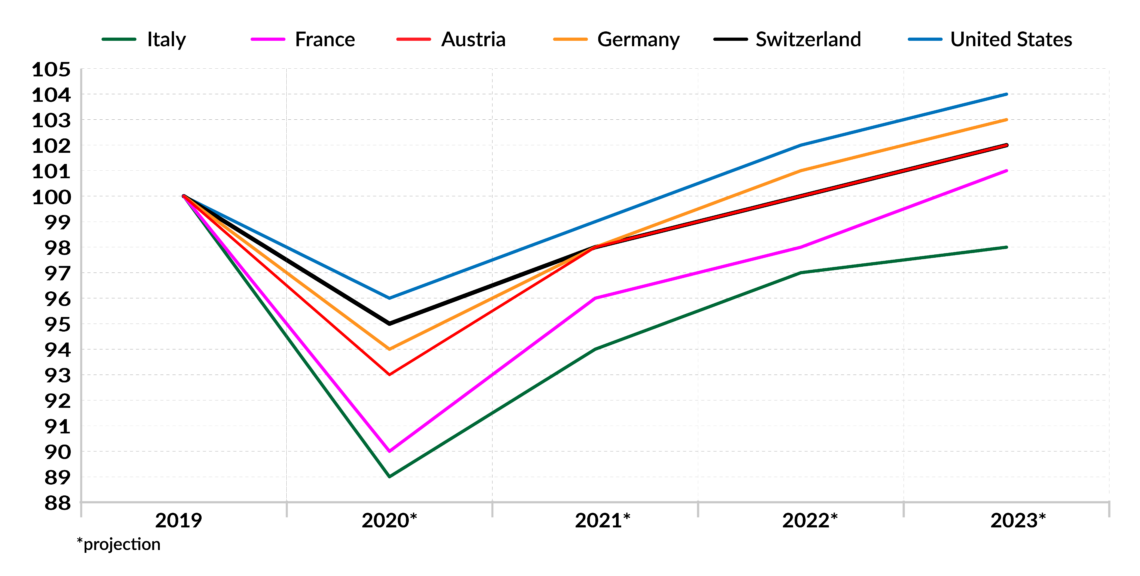

To assess the reopening, we need to review the economic effects of the lockdown. The most immediate was a drop in economic growth. All European and North American economies fell into recession – the deepest in 50 years. In fact, the first half of 2020 was the first time since at least 1870 that 90 percent of the world’s economies suffered from a recession simultaneously.

This big-picture view does not give us insight into economies’ microeconomic structures, but it is crucial to understand the smaller-scale processes, since they combined to create the overall effect. The local-level makeup of an economy is a crucial factor in determining how to restart it after a lockdown successfully, as shown by the bottom-up approach. Whatever happens on the small scale manifests itself in the macroeconomic picture.

The local-level makeup of an economy is a crucial factor in determining how to restart it after a lockdown successfully, as shown by the bottom-up approach.

By not allowing businesses to operate at all, a lockdown interrupts an economy’s processes for adding value. As such, it not only deprives businesses of liquidity, but also breaks the markets’ constant information feedback loop. Businesses that do not exchange with customers and suppliers and that do not constantly seek to differentiate themselves in the competitive process are less adaptive, less agile and less innovative.

A lockdown also affects capital and labor markets. Capital markets are aware that businesses have become less dynamic, which leads them to discount their investment valuations. Labor markets are affected primarily by businesses laying off employees, but also by new workers – like those just finishing school – being unable to enter the market.

What works, what doesn’t

In most locked-down economies, governments tried to stem the bleeding by boosting demand- and supply-side stimuli, as well as adopting an accommodating monetary policy. In German-speaking countries, the already existing Kurzarbeit programs (see box) partially guaranteed the income of the workforce and the continuity of their jobs. Some countries offered liquidity facilities (promises to refinance debt) to ensure that businesses could keep paying the bills.

These instruments were intended to mitigate the damaging effects of the lockdown. They were not intended as a cure-all or long-term solution, but were only expected to bridge the gap until reopening. Some instruments fared reasonably well. For example, Kurzarbeit prevented mass unemployment and maintained demand. In fact, in German-speaking countries, consumer spending remained robust during the lockdown, migrating from brick-and-mortar stores to online channels. The liquidity facilities also generally worked as intended.

Other instruments did not work as well. Accommodating monetary policy, in place at least since 2009, produces capital markets with valuations that are not in tune with the real economy. In times of recession, when there is a natural squeeze on the low and middle classes, accommodating monetary policy further skews the distribution of wealth further toward the rich.

The stimulus packages are altogether counterproductive. The European Union’s 750 billion-euro package, for example, will certainly increase the damage created by the lockdown. These initiatives push out more productive private investment and try to socially engineer (that is, plan) the EU’s economy from the top down. The health sector, which thrived economically during the lockdown and its aftermath, is one of the largest recipients of funds. So are the “green” businesses that were already living on EU subsidies before the lockdown.

Competition, not planning

Both accommodating monetary policy and stimulus packages presuppose a neutral, all-knowing central planner. This is an especially acute problem in stimulus packages. The European Commission believes that it can know how the economy of the future will look, that it can plan for the economy to transit into that future and that it can do so “justly.” This set of assumptions is wrong. It not only disregards almost any insight produced by economic science. It is especially faulty because it disregards the nature of economic exchange.

The most important lesson of the lockdown might be the enormous impact that the loss of business dynamism has on an economy. Businesses that are disconnected from the chain of information and value addition fall into paralysis. They lose agility and innovativeness. The same applies to capital and labor markets. Paralysis is probably the most negative effect of the lockdown on the economy. If an economy is to come out of its stupor, it needs businesses to regain their vitality.

Businesses that are disconnected from the chain of information and value addition fall into paralysis.

To do that, businesses need to face novel situations and find differentiated ways of dealing with them. As competition develops, businesses regain dexterity and originality. In the context of restarting an economy, it could mean allowing businesses to reopen unrestricted by regulation.

For example, instead of making masks mandatory, governments could simply establish that businesses must take precautions while reopening. Each business on its own would then take precautions as deemed necessary and adequate. Another example: instead of regulation setting out which types of staff can work “traditionally” and which “remotely,” it could allow businesses to decide for themselves how to organize their work. In both cases, businesses would take responsibility into their own hands and seek to differentiate themselves, creating some competition.

Bottom-up results

Bottom-up approaches maintain the microeconomic tissue of entrepreneurialism. Most of all, they lead to dealing with new challenges in unique ways. Certainly, reopening a business while maintaining a public health standard or organizing work are not the most imaginative challenges. But letting entrepreneurs think about how to overcome these problems responsibly, while also differentiating themselves in doing so, encourages them to regain their agility.

Facts & figures

Reigniting dynamism and innovativeness is the most crucial aspect of restarting an economy after a lockdown. Preliminary results show that economies that chose this course are in better shape than the ones that took a top-down approach. Liechtenstein, for example, was quick to restart its partially locked-down economy by granting businesses a lot of freedom in reopening. Its economy is recovering better than expected. Switzerland took a similar but slower path, and is also recovering faster than many thought possible.

In the Swiss case, the preliminary results allow for an even bolder comparison. Switzerland’s increase in productivity in recent decades lagged behind Germany’s. After the lockdown, Switzerland opted for a relatively liberal restart while Germany chose one of the most centrally planned, micromanaged restarts in Europe. The result: Switzerland’s productivity surpassed Germany’s in the second and third quarter of 2020. In fact, Germany’s tightly regulated restart, awash in stimulus money, pulled its productivity down below that of France or Italy.

Bottom-up restart approaches capitalize on the main assets of an economy: business dynamism. Top-down approaches, instead of pushing firms to be agile and innovative, prolong the stupor caused by the lockdown. They extend recession and can even cause a more serious crisis.

Scenarios

As the recession continues, three broad scenarios for further economic development are possible. They might also combine to some degree.

The great divide

In this scenario, economies with bottom-up approaches will recover quickly, while those with top-down policies will prolong the global recession. Since the second group is larger than the first, its economic sluggishness will drag all economies down. In this case, the return of economic welfare to the level of the year 2019 in Europe and North America will take at least until 2023.

The great stumble

Due to political pressure, the group of economies relying on bottom-up approaches will switch to top-down tools. This could lead to macroeconomic revitalization, but at the cost of weakening the microeconomic tissue of the respective economies. In this scenario, recovery lasts until 2025 and unemployment rises during 2020 and 2021, perhaps longer.

The great emancipation

Economies relying on bottom-up approaches gain traction and change how they interact with the others, essentially emancipating themselves and finding other business partners. In this case, recovery should happen by the end of 2021 and unemployment rates would quickly decrease after a peak in mid-2021.

Of these three scenarios, the first one seems the most probable.