Romania’s paradox

Outwardly chaotic and dysfunctional democracies can deliver economically. Romania is a case in point.

In a nutshell

- Romania’s buoyant economy shows underlying strength of governance

- The EU and NATO member scores high on an important economic index

- An informal power structure harkens to the monarchical period of 1881-1947

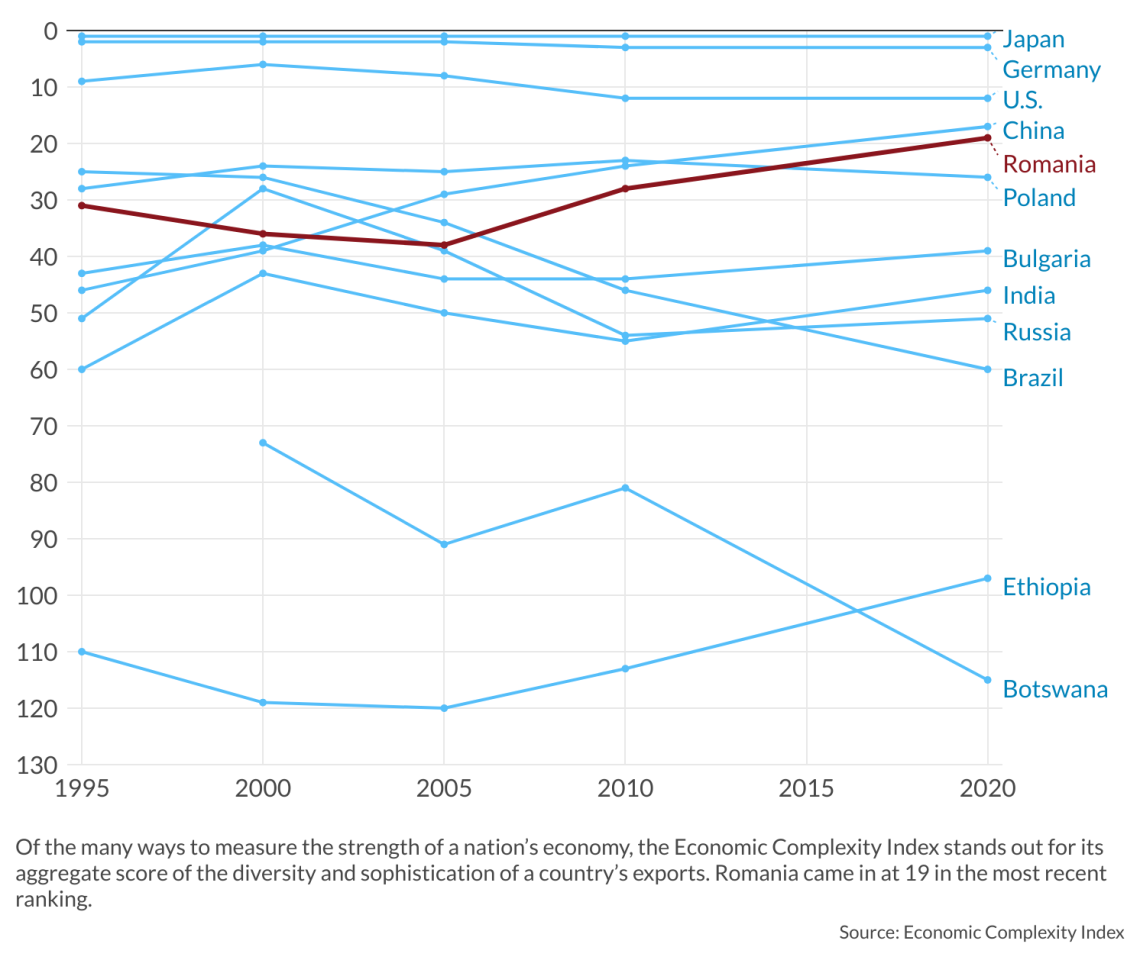

The Economic Complexity Index (ECI) built at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government is a measure of the productive capabilities of a national economy but can be applied to cities and regions as well. The index aggregates information about the diversity and sophistication of a country’s exports. Countries improve their ECI by increasing the number and complexity of the products they export. The latest data reveal a rather surprising fact: By ECI’s account, Romania’s economy is the 19th most complex and sophisticated in the world. That was a revelation to many – including to many economists and decision-makers in the southeastern European nation of 19 million people. The nation has been on an upward trend since 2000 when ECI initially ranked Romania 39. The rise puts Romania just behind China (17) and France (18) yet ahead of Mexico (20) and Israel (21). Regionally, Romania looks even better compared to the historical rankings of Poland (26), Bulgaria (39) and Ukraine (49). Of course, a rise by some nations means a drop by others. For instance, Brazil dramatically plunged from 25 to 60.

The ECI is considered a reliable estimate of a national economy’s performance. It is a more nuanced instrument of the potential and structural capabilities. It is also a factor in explaining the trends of more traditional measures, such as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Its tracking of the Romanian economy is institutionally corroborated by a memorandum for accession to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that was formally submitted by the Romanian prime minister in 2022. The OECD announced that Romania will be one of the six candidate countries with which it would open accession talks.

Economic prospects are bright

Romania can look to more economic growth ahead. An average of forecasts (coming from an array of sources, including the World Bank and private investment firms) puts Romania’s annual growth rate for the next five years at between 2.5 percent and 4.5 percent. Romania is already now the largest economy in southeastern Europe. The chief economist of one of the largest Romanian banks (Banca Transilvania) has even predicted that Romania’s GDP per capita, measured for purchasing power parity (PPP), will likely catch up with the European Union average around 2030. The International Monetary Fund puts the Black Sea nation’s nominal GDP in 19th place among the EU’s 27 national economies, with per capita GDP PPP at 74 percent of the EU average in 2021.

The findings are surprising and even paradoxical. The upbeat economic performance is at odds with the checkered reputation of Romanian politics, governance and institutions. Romania’s international image is often associated with internal tension and impasse. The nation has a history of friction with the EU and the West over corruption and institutional dysfunction (see the recent Schengen accession spat with Austria). The political class is also seen as unstable, unreliable and untransparent. Hence the Romanian paradox: Impressive economic performance despite the perception of unimpressive governance and political processes.

Natural questions arise: How is this possible? What is going on? Are there errors of perception, either regarding the robustness of the economy or the flaws of politics? Are there any lessons to be learned?

Facts & figures

A coalition government delivers stability

The relative political stability achieved recently by Romania is at odds with some events of the last 20 years. Structural crises several times reached the level of constitutional emergencies. One involved the 2012 constitutional crisis, regarded by many as a de facto coup d’etat by then-Prime Minister Victor Ponta and parliament against then-President Traian Basescu. The current situation in which the two major parties, one from the left (Social Democratic Party – SDP) and one from the right (National Liberal Party – NLP) are part of a national coalition government has been the result of pressures put on Romania by the Covid-19 crisis and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

So far, this coalition arrangement has proven to be a very effective and stabilizing solution. Romania seems to have navigated successfully both the turbulence of the pandemic and the regional shock of the war in Ukraine. This relatively calm situation may roll over to the next election cycle. But the 2024 general election campaign will test the coalition politically and could expose the internal frictions of the recent years of coexistence in power.

Another noteworthy aspect of this moment of equilibrium: As in other cases of grand coalitions, space for the emergence of a third political force is created. Usually, such a third force takes an antiestablishment stance, challenging the status quo. In Romania’s case, such attempts to be the third political force have been mounted both from the left and from the right. The attempt from the left by the Save Romania Union (SRU), which embraced a radical Western progressive agenda, seems to have exhausted itself in a series of political errors, scandals and ideological overreach. The attempt from the right by the Alliance for the Union of the Romanians (AUR) has been much more successful and resilient. AUR, which has embraced a euroskeptic and pro-national sovereignty tenet, is positioned in the opinion polls as the third political force, with support of around 20 percent.

The tensions ahead of the 2024 elections raise questions about whether the current stability will last or whether traditional turbulence will resume.

Two-tiered governance structure

The situation reinforces the Romanian paradox: Impressive economic performance mixed with unimpressive governance and political processes. How to explain such a situation?

One possible explanation is a historical accident that will dissipate sooner or later, since such a glaring contrast between governance and economic performance is not sustainable in the long run.

A second explanation may involve a rethinking of Romanian politics. Romania may be an excellent illustration of the “myth of democratic failure” thesis – an apparently chaotic and dysfunctional democracy that delivers impressive economic results.

But a possible third direction is even more interesting and intriguing. It involves making the distinction between the political state, including the typical democratic and liberal institutions, and the underlying governance structure, which combines various actors and institutions exerting their power. This analytical approach has solid and respectable roots in elite theories of democracy, public choice theory and social conflict political sociology. It may offer insights regarding such two-tier governance architectures, which may be an emerging global trend, including in advanced industrial democracies.

In Romania, the underlying and often less publicly visible structures of governance and power have functioned well enough in the last 20 years or so. The informal power center can be loosely defined to include a mix of administrative and technocratic elites in agencies and national organizations, defense and intelligence services, decision-makers in state-controlled economic domains or strategic private industries, as well as regional and local political and electoral networks.

The nation has shown continuity, stability and resilience, not only mistakes and turbulence. The collective governing structure has had notable successes. It marginalized the oligarchs who were typically such a strident and disruptive presence in other postcommunist countries. It practiced politics consistent with European values. While not always in full conformity with best practices, the governance structures were effective enough not to jeopardize decent economic and political performance.

Facts & figures

A throwback to monarchy

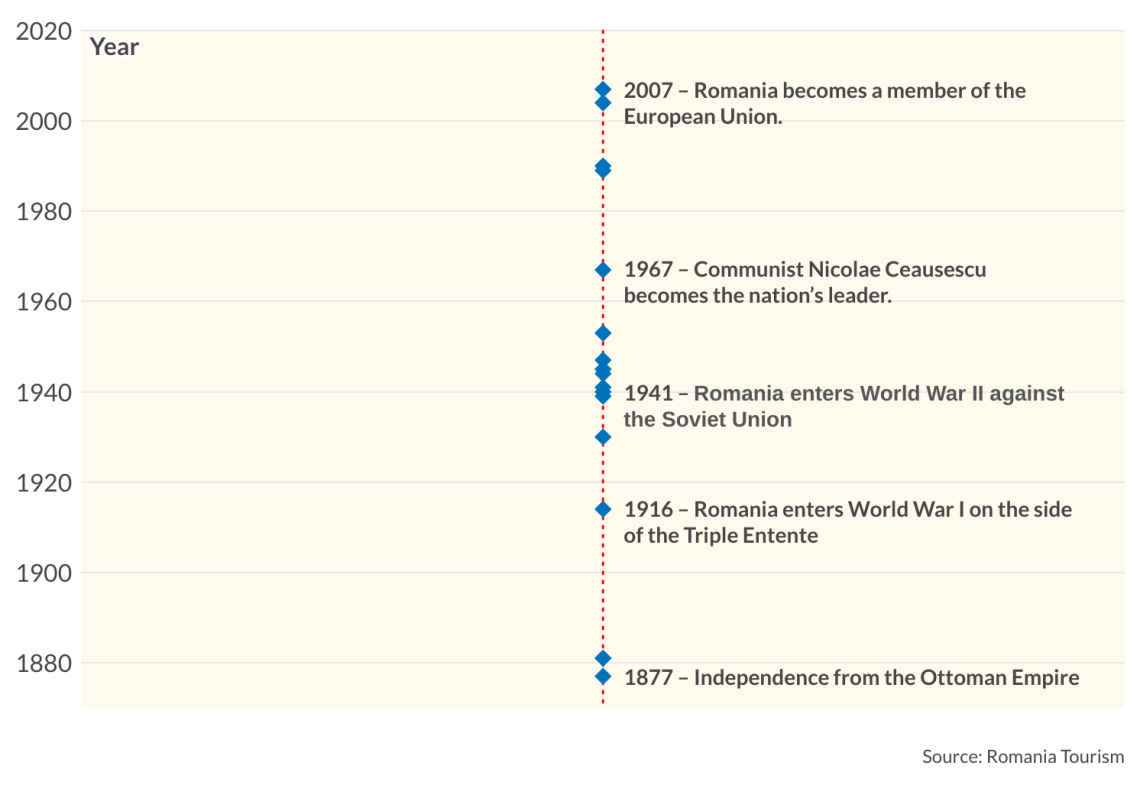

Historical forces are at work. The Romanian paradox may, in fact, be attributable to a return to how the nation’s parliamentary system operated in the precommunist era, particularly the monarchy in existence from 1881-1947. Then, a so-called “rotating government” could be defined as an administered democracy. It was a time in which a multiparty establishment elite, pivoting around the king, determined the electoral and political process in semitransparent arrangements. The current Romanian governance system seems to have gravitated toward this traditional model.

A two-tiered governance system has emerged from ongoing technological, geopolitical, institutional and cultural transformations. The equilibrium between public structures with legal governing authority and underlying traditional power structures is changing. It may be part of a global trend, even among advanced industrial democracies, with a wide range of governance arrangements between the two tiers. In some countries, the public institutions are dominant; in others, the balance of power lies with resurgent underlying structures. Romania may be a good illustration of these trends and an example of how such governance systems work.

Scenarios

The Romanian paradox offers two clear scenarios, both with equal chances of prevailing.

Under a two-tiered system in which the second tier has an edge, everything hinges on whether the underlying operating structure will function adequately and deliver desirable results for the economy and society.

Status quo governance and continued positive trends

More of the same: The two-tier governance model continues to operate, driven by the underlying components. The seemingly dysfunctional democratic and governance system will be marked by confusion, uncertainty and political malpractice. But it will also be associated with surprisingly robust economic performance because of the traditional strengths. The Romanian system may be an illustrative case study of a successful Western-oriented “administered democracy,’’ not a fully liberal-democratic one but neither an authoritarian one.

Disruption of the underlying structure, leading to a crisis of dissolution

An alternative scenario factors in possible fractures and dysfunctions emerging at the underlying level of governance structures. The interplay between formal and informal institutions, social networks and economic and political interests may break down. Such an evolution may paradoxically be associated temporarily with a more open and democratic political competition on the surface.

But once the tectonic plates of postcommunist Romania get destabilized and are set on a collision course, the entire structure will be in danger over time. Then, the fragility of the system will be exposed. If and how the collapse will be managed will be a matter of whether Romania becomes part of the eurozone and what role the EU and NATO will play in southeastern Europe and the Black Sea region.

Under this second scenario, the Romanian system will illustrate the dangers of building an asymmetric relationship between the “surface” and the “deep” state, with the inherent lack of checks and balances.