What’s behind Russia’s ‘ruble clause’?

The Kremlin’s attempt to make “hostile countries” pay for energy imports in rubles is problematic for a host of reasons. Is there more to this move than meets the eye?

In a nutshell

- Russia has pulled out all the stops to shore up the ruble

- Forcing energy customers to pay in rubles could backfire on Moscow

- Retroactively imposing the “ruble clause” would hurt the Russian economy

In contrast with the 2014 invasion, occupation and subsequent annexation of Crimea, the Western response to President Vladimir Putin’s military intervention in Ukraine this time has probably caught the Russian authorities by surprise: trade has been severely restricted, Western companies have come under pressure to move out of the country, Russian foreign-currency reserves held in the West have been frozen.

Not only has Russia been all but cut out of major financial systems, but the ability to use gold stocked at the Central Bank of Russia has also been limited. Certainly, this wave of sanctions is not watertight, and Moscow can still do business with a large part of the world, including China and India. Russian endurance, patriotism and propaganda will probably persuade many Russians that putting on a brave face and making sacrifices are more important than economic growth. Yet, although sanctions will not devastate the economy and cause unbearable difficulties for the population and Russia’s current leaders, they will continue to take their toll, especially in the long run.

‘Ruble clause’

Several things went wrong from the Kremlin’s perspective, and the strongest reactions came from the financial sector. As many Russians perceived that something was not going according to plan and that months of trouble were probably in sight, they snapped up all sorts of consumer goods. The run on the supermarkets and durable goods in general, fueled by the sharp increase in the supply of rubles registered in the last quarter 2021, led to soaring consumer prices.

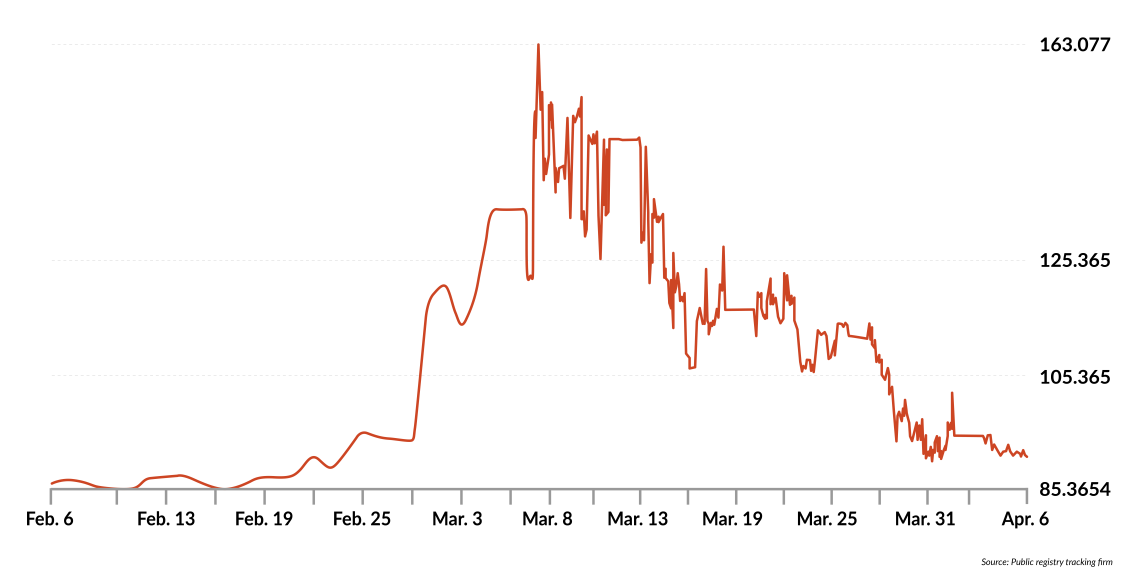

In mid-March 2022 annual inflation neared 15 percent but was running at a weekly rate not much below 2 percent. At the same time, those who could tried to exchange their ruble-denominated cash and assets into dollars and euros. The result was a rapid depreciation of the ruble, from about 85 rubles per euro in early February to about 150 rubles per euro on March 10.

Russia blamed the West for the drop in the ruble exchange rate.

Understandably, the Russian authorities blamed the West for the drop in the ruble exchange rate, and depreciation for inflation. At the same time, they reacted by enforcing capital controls, restricting convertibility, offering more rubles to support bank liquidity and raising interest rates on ruble deposits.

Shortly afterward, they also announced that in the future Moscow would honor its euro- and dollar- denominated debts, but would ask “hostile countries” to pay for their energy imports in rubles. Some dubbed this policy the “ruble clause.”

The authorities can now boast that the ruble has stabilized. By the beginning of April, one euro bought 85 rubles, marking a slightly stronger exchange rate than before the war began. Western operators are perhaps not overly interested in Russian monetary policy. But what about the ruble clause? Is it little more than a flash in the pan with little practical relevance, or should we take it more seriously?

Domestic drivers

Requiring payments in rubles barely changes the picture on the international scene. Perhaps it is an attempt to transform the ruble into an international means of payment. If so, the move is premature, to say the least. It is more likely that the current efforts to polish the ruble’s image are prompted more by domestic issues than by an ambition to play a bigger role in the international money market.

The presence of a ruble clause for Russian energy exports means that importers must buy rubles to pay Russian exporters. Since there are currently limited amounts of rubles available on foreign currency markets, the main way of getting hold of them is to buy them from the Russian central bank at a price (the exchange rate) set by the central bank.

At the end of the day, therefore, Western “hostile” importers will still pay for their imports in dollars or euros, but their counterpart will be the central bank, rather than the exporting companies. Does that make a difference? The answer depends on the price-setting mechanism, which leads to the second comment.

Facts & figures

Ruble-euro exchange rate

February-early April 2022

Energy contracts have usually been denominated in dollars and euros. There is good reason for this. In a world characterized by globalized transactions, the relative price of energy, i.e., the price of energy relative to all other goods and services, depends on supply and demand. Exchange-rate manipulation does not cause much distortion.

For example, French exporters of nuclear power or Saudi oil producers can hardly alter the nature of a contract by manipulating the exchange rate of the euro or the dollar after the contract has been signed. This explains why the dollar and the euro are successful international currencies.

International currency?

But things would be different if the Russian central bank restricted full convertibility of the ruble (for example through controls on capital flows), or if the ruble exchange rate were heavily influenced by the price of a limited number of goods or commodities (like gas and oil). One can perhaps argue that buyers could eliminate the exchange rate risk by buying rubles on the forward market – that is, by agreeing today on the price at which rubles will be bought and sold in the future. In turn, the presence of a thriving market for exchange rate derivatives would encourage operators to accumulate rubles to meet speculators’ demand.

If that were to happen, the ruble would gradually acquire the role of international currency and the Russian central bank would reap the benefits of seigniorage: selling rubles at no cost (except the cost of printing). Is that realistic? Can the Russians enjoy the free ride of seigniorage by introducing a ruble clause? The answer is no. Seigniorage is not up for grabs. It is the reward for a reputation for convertibility and relative stability. The Russian central bank lacks both.

If Moscow were to try and apply such a clause, it would signal its decision to default on Russia’s dollar- and euro-denominated debts.

The picture would be different if the proposed switch to ruble-only payments applied to previously agreed dollar/euro-denominated contracts that must now be honored in rubles at an exchange rate dictated by the Russian central bank. This would clearly amount to a breach of contract. Insisting on such a change would represent a self-inflicted blow: it would undermine Russian operators as commercial counterparts and would probably damage the Russian economy more than the sanctions currently in place.

Put differently, if Moscow were to try and apply such a clause, it would signal its decision to default on Russia’s dollar- and euro-denominated debts, at least on those held by “hostile countries.”

Circumventing the sanctions

If the ultimate goal is to avoid default, the explanations for requesting ruble-denominated payments must lie somewhere else. There are two plausible answers.

One is inward-looking. The Russian authorities need significant quantities of accepted means of payment (gold, dollars and euros) to circumvent the Western financial blockade. As mentioned above, avoiding the blockade is possible (perhaps through Asian and Latin American countries), but it will not be cheap.

The ruble clause would cut out the energy companies from the payment system and help those dollars make their way to Moscow.

Hence, President Putin must ensure that all foreign currency proceeds from energy exports find their way to the Russian central bank, rather than staying parked in opaque shell companies and Western bank accounts. The ruble clause would cut out the energy companies from the payment system and help those dollars make their way to Moscow.

The second answer relates to the possible creation of a hard, commodity-based ruble, as opposed to its present fiat status (paper money). A “hard ruble” would possibly be the best way of boosting Russia’s prestige, killing inflation and meeting Russians’ expectations for a stable currency, not unlike what happened in Soviet Russia, when Lenin introduced the gold-backed “chervonets” in October 1922.

Is that a feasible project? Could oil or gas replace gold as the commodity standard? Could that pave the way for other commodity-based currencies, like the Chinese yuan?

Scenarios

The answer is mixed. A hard ruble would probably be a partial domestic success, but only if it were really hard – gold coins that individuals can hold and possibly hide away. Liquid rubles – certificates (paper money) backed by oil and gas – will not do because people would not trust a commitment to convert paper into gold, let alone into gas or oil. Yet, liquid rubles could be the reference for a monetary standard similar to a currency board, a corset that would prevent the central bank from pursuing discretionary monetary policy.

It is doubtful that monetary rigor is Moscow’s goal. Of course, lack of faith in convertibility would dissolve if Russia’s gold reserves were parked outside Russia. The Kremlin would never consider that option, though. The same would be true for Beijing. Indeed, one can conclude that the recent international tensions have probably killed all grand-scale projects for a golden yuan, too.