Russia’s cyber fog in the Ukraine war

The all-out Russian war effort to conquer Ukraine will lead to a rise in cyberattacks on both Ukrainian and Western critical infrastructure.

In a nutshell

- Russian cyberattacks are more frequent since the invasion of Ukraine

- Hacker groups could start striking at more specific targets

- Vulnerabilities will increase with the rise of digital technologies

Russia’s state-supported cyberattacks increased both before and during its invasion of Ukraine. The moves are part of Moscow’s broader attempt to disrupt services and create intimidation and confusion. Up until now, however, the Kremlin has not launched a devastating cyberwar against NATO countries, despite numerous warnings in recent months.

Western experts are still uncertain whether fears of American cyber retaliation and the existence of a “Mutual Assured Cyber Destruction” (“cyber-MAD”) are the reason why such attacks have not materialized. But any further Western sanctions (such as the European Union’s declared oil embargo on Russia) will increase the risk of devastating Russian cyberattacks.

Shared targets

On May 10, 2022, the European Union, United Kingdom and the United States officially attributed a February 24 cyberattack to Russia. One hour before the invasion of Ukraine, hackers had targeted the Viasat-operated KA-SAT satellite network to disrupt command and control of the Ukrainian military and government communications.

The disrupted internet access caused collateral damage to commercial and residential internet services. Thousands of modems across Central Europe lost their satellite connection. In Germany, 5,800 Enercon wind turbines could no longer be remotely monitored by their operators.

In 2015, Russia conducted its first deliberate cyberattack on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure and grid system.

Since the invasion, Russian attacks have become more frequent and destructive. They are coordinated with the Kremlin’s military actions as part of its hybrid warfare against both Ukraine and the West. Its state-supported hacker groups began preparing for the conflict as early as March 2021, according to new reports on Russia’s relentless cyberattacks as part of its hybrid warfare against Ukraine. These cyber operations require careful planning, targeting and development, which requires months if not years.

In recent years, both the U.S. and EU have intensified their collaboration with Ukraine on cybersecurity. This is because Ukraine has become a testing ground for Russia’s advanced cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, and the West can learn much from Russian cyber strikes against Ukraine.

Facts & figures

The Colonial Pipeline hack

In 2015, Russia conducted its first deliberate cyberattack on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure and grid system. In 2017, the Kremlin-backed NotPetya virus, designed to disrupt financial, energy and government sectors in Ukraine, spread internationally and cost companies around the world over $10 billion in damages.

For the EU, strengthening the cybersecurity of Ukraine’s critical infrastructure has become increasingly important since the Ukrainian electricity grid is being integrated into the EU’s common electricity market and network (ENTSO-E).

The rising vulnerabilities of Western societies and economies have been highlighted in 2020 after the hack of a leading U.S. security tech company and its software (SolarWinds). It gave the Russian hacker group “Cozy Bear” (also called “Nobelium” or APT-29) access to thousands of companies’ data, as well as critical infrastructure in various countries. The targets of this hacker group are believed to reflect the Kremlin’s geopolitical interests and strategic priorities. Cozy Bear has increased its attacks against Ukraine from a mere six in 2021 to more than 1,200 this year, with particular focus on the Ukrainian government and its state agencies.

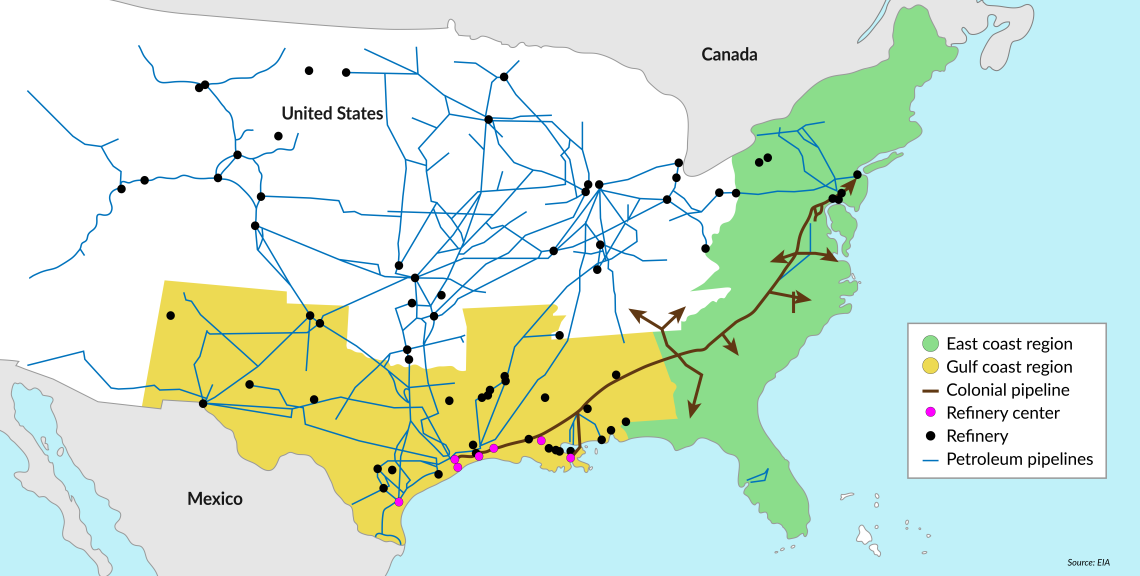

There are also lessons to be learned from the ransomware cyberattack on the 8,000-kilometer U.S. Colonial oil pipeline. In May 2021, hackers infiltrated the company’s information technology infrastructure and were able to disable the pipeline’s operation. The hack affected the oil supply for both private consumers and U.S. Armed Forces, leading to panic buying. The attackers stole nearly 100 gigabits of data and requested a ransom of 75 Bitcoin ($4.4 million at the time) to return access to the company’s billing system. The company eventually paid the ransom to the cyber hacker group DarkSide, despite the government’s efforts to prevent this. In response, the Biden administration passed the Strengthening American Cybersecurity Act (SACA) last March. It requires federal agencies as well as owners and operators of critical infrastructure to report cyberattacks within 72 hours and ransomware payments within 24 hours. But how to better mitigate threats and enhance resilience collectively across industries and sectors is not addressed in the SACA.

Mutual escalation

Since the war in Ukraine began, Russia’s state-backed cyberattacks against Western critical infrastructure have increased – by as much as 72 percent in the U.K. Alongside ever more Western sanctions and the increasing supply of heavy weaponry, NATO countries fear that Russia could escalate its nascent cyberwar with sophisticated strikes against critical infrastructure. NATO governments and the European Central Bank have repeatedly warned that the West should be prepared for this eventuality.

The Five Eyes intelligence-sharing network among the U.S., the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand stated in April that Russia was planning massive cyberattacks against Western countries supporting Ukraine. A dozen hacking groups were designated as threats, since they are part of, or close to, Russian intelligence and military institutions. They have the ability to anonymously compromise IT networks, steal large amounts of data, deploy destructive malware and bring down networks.

Last October, Microsoft warned in its 2021 Digital Defense Report that Russia was the state that posed the greatest cyber threat. Russian hackers are considered much more prolific than those from China, Iran and North Korea. In 2020, 58 percent of all state-backed cyberattacks identified by Microsoft came from Russia. Cozy Bear accounted for more than 92 percent of all detected Russian activity. Microsoft also warned that its attacks targeting enterprise VPN software have become up to 32 percent more successful. Attacks are mainly carried out as espionage and intelligence campaigns against government agencies and think tanks. The top target countries are the U.S., Ukraine, and the UK.

During its 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia learned that it is much more difficult to conduct a surgical cyber strike than an indiscriminate one.

In March, the White House issued a strongly worded warning that Russia is planning major cyberattacks against the U.S. in retaliation for its harsh economic sanctions. In April, a U.S. federal advisory warned that hackers with ties to foreign governments are targeting specific industrial processes and their information and control systems, including the supervisory control and data acquisition devices to disrupt, sabotage and physically destruct them.

Last June, U.S. President Joe Biden, embarrassed by the SolarWinds hack and facing political pressure to retaliate against Russia, issued a warning to President Vladimir Putin. At the first bilateral cybersecurity summit since the Kremlin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Mr. Biden stated that 16 areas of critical infrastructure, including energy, health and water, should be “off-limits to attack” by cyberattacks or other means.

He also urged the Kremlin to take action against criminals conducting ransomware attacks. But bilateral cybersecurity cooperation has not made any significant progress since last summer. Illicit ransomware activities by criminal groups appear to have continued unabated. The trend goes hand in hand with the booming cryptocurrency industry, which provides anonymous digital assets that can be used for money laundering.

‘Cyber-MAD’ and cyber deterrence

Alongside diplomatic efforts to de-escalate cyber tensions between the West and Russia during the last few years, Western allies have warned Russia of “massive consequences” for its largest banks and trading companies in the case of escalating cyberwarfare against NATO and EU countries.

Despite Russia’s undeniable offensive cyber capabilities, the Kremlin has not initiated any larger devastating cyberwar against the West since its military invasion began – despite unprecedented sanctions.

One explanation could be that both the U.S. and NATO have stated that a highly damaging cyberattack on any member of the alliance could trigger Article 5 of the treaty, which guarantees mutual defense. This could indicate that some form of “cyber MAD” still functions between the U.S. and Russia. Many cyber experts have warned that the West cannot afford to bet on that as a deterrent. However, defining a more assertive cyber retaliation strategy must also consider the possibility of an escalatory spiral that could even result in Russia resorting to use nuclear weapons, even perhaps preemptively.

During its 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia learned that it is much more difficult to conduct a surgical cyber strike than an indiscriminate one. If the Kremlin decides to directly attack major Western infrastructure, it will face retaliation. But the situation could also escalate because Russia might not always be able to control its own cyber operations on selected targets, potentially leading to unwanted escalation and collateral damages far beyond what was initially intended.

Facts & figures

Rising threats

Since the beginning of the war, Russia itself has become the target of numerous international pro-Ukraine cyber groups and hackers, shattering illusions of Moscow’s cyber superiority. Cyberattacks on the Russian government and military institutions have increased significantly. The active Anonymous group has stolen hundreds of millions of documents from governmental and industrial websites, including the Ministry of Defense. Others have blocked or slowed freight trains carrying Russian military equipment or tampered with the automatic ticket system for passengers.

Ukraine itself has built an “army” of IT volunteers (like Network Battalion 65) to protect the country against Russian hackers, but also to launch counter operations against Russian cyber threats. The Ukrainian cybersecurity company Hacken claims that 10,000 hackers from 150 countries have volunteered to disrupt Russian media sites and promote pro-Ukrainian messages across Russian social media.

But these international and private Ukrainian hacker groups have acted without any kind of coordination, in contrast to Russia’s state-supported cyber groups controlled by the foreign intelligence agency (SVR) or the military intelligence agency (GRU). Hence, the impact of these international cyberattacks against Russia has yet not been significant enough to shift the Kremlin’s cost-benefit calculation of its invasion of Ukraine.

Scenarios

Russia’s red lines and escalation strategy could further change in the weeks and months ahead. How the military, political and economic aspects evolve, and war aims change will influence how the Kremlin decides to use its cyber capabilities in the conflict.

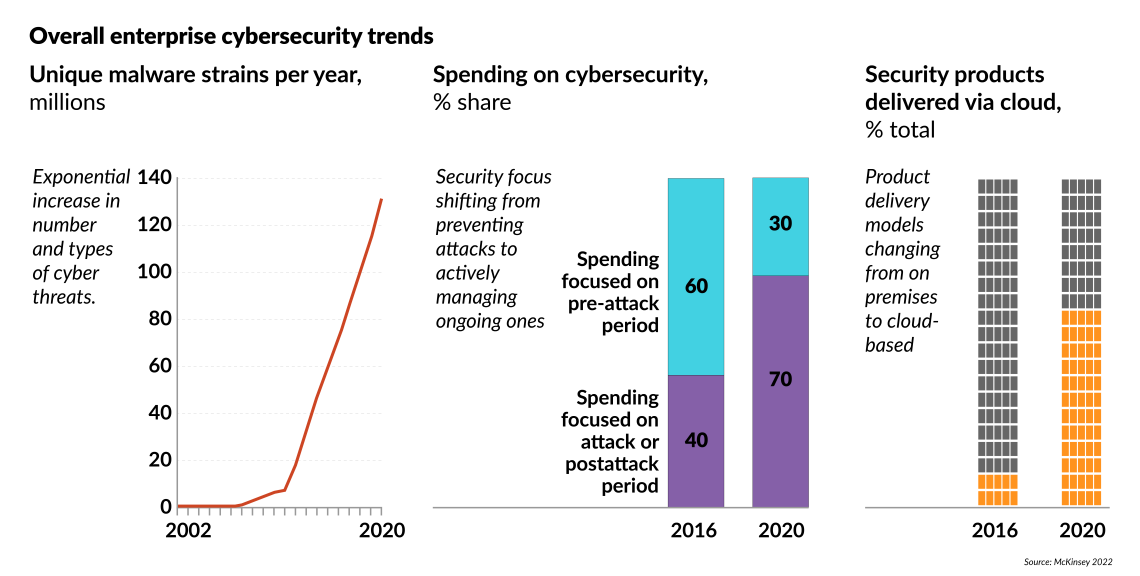

Beyond the Russian-Ukrainian war, if adversarial threats increase, so too will the vulnerabilities, as the world increasingly relies on digital technology. In 2021, a record-breaking number of cyberattacks took place – a 50 percent increase from the previous year according to the cybersecurity firm Check Point Research. New forecasts suggest that 2022 could be even worse. Cyber threats to civilian and military critical infrastructure are likely to multiply and grow even more consequential as the digital and physical worlds become increasingly intertwined. While awareness of the need for cyber resilience has grown in the West, it is too little to prevent disastrous cyberattacks on critical infrastructure.