Waning prospects for Russia’s Eurasian vision

Moscow’s geopolitical vision of a “Greater Eurasian Partnership” sets Russia at the center of continent-wide political and economic cooperation. Its 2012 pivot to Asia was part of this strategy. To achieve its goal, however, Russia needs to stand on equal footing with Europe.

In a nutshell

- Putin’s relationship with Europe is deteriorating

- Russia wants to compensate by building a Eurasian partnership

- Economically and politically, that plan has major problems

Relations between Russia and the West have sunk to new lows, raising fundamental questions about what that means for both sides’ future. The crisis in Belarus has shown that the Kremlin will take whatever steps necessary to keep its grip on that country. The attempted murder of Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny has demonstrated it is ready to pay a steep price to halt his activities. The brazen denial of foul play shows it remains determined to avoid responsibility.

Given the growing mutual animosity and the high geopolitical stakes at play, the strategic options must be made clear. The point of departure is this: Russia remains inextricably linked to Europe for a host of reasons. Both sides must come to terms with this fact.

Eurasian vision

The critical question is whether Russia can build a prosperous future for itself in which it is not part of Europe. The Kremlin’s “Greater Eurasian Partnership” vision is based on the notion that economic and political cooperation within Eurasia will allow Russia to interact with Europe on more equal terms. Europe, for its part, would have to accept a greatly reduced role in the east.

If Russia fails, it would mean having severed bonds with Europe without building compensatory links within Eurasia. That would deepen socioeconomic rifts and increase threats to regime stability. Resentment over the loss of prestige would inflame anti-Western sentiment.

The Kremlin’s pivot to Asia began in 2012. The ambition was to attract much-needed investment, propelling the economy.

While the Ukraine crisis was a critical moment in setting Russia and Europe on a collision course, Moscow’s plan to turn eastward began well before. The Kremlin’s pivot to Asia dates back to 2012 when Russia hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Vladivostok. President Vladimir Putin’s clarion call at the time was for the Russian economy to “catch the Chinese wind” in its sails. The ambition was to attract much-needed investment, propelling the struggling economy toward sustainable growth.

Though this economic shift was important, the broader issue is Russia’s “civilizational identity,” which boils down to its complex relationship with Europe. Although this has been the topic of intense debate over the past half-millennium, its geopolitical implications are crucial today.

The Soviet Union’s collapse revealed the core of the problem. Against the Russian vision of a “Greater Europe,” that would eliminate all vestiges of Cold War separation, Europeans touted a “Wider Europe,” with Brussels deciding whom to include. In 2010, then-Prime Minister Putin still espoused the idea of a free trade zone “from Lisbon to Vladivostok.” In an interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel, he envisioned “a unified continental market with a capacity worth trillions of euros.”

The ambition was to build a set of institutions that would make it possible for Moscow and Brussels to cooperate as equals. The flagship of this initiative, the Eurasian Union (EAEU), was largely patterned on the European Union. One of the EAEU’s very first moves after its 2015 launch was to seek cooperation with the EU.

That was only five years ago, but already it seems like ancient history. As the Ukraine crisis drags on, the vision for cooperation has been replaced by a regime of sanctions and countersanctions that has severely harmed trade and development.

Russia’s pivot to Asia has therefore become a matter of defying Europe. What makes the task especially challenging for the Kremlin is that it entails a dual approach to China. While seeking to profit from Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it also aims to rein in the Middle Kingdom’s mounting influence by building a network of partnerships with other countries in the region. The outlook for success in either of these ambitions is dim.

Failed economic transformation

As the crisis between Russia and the West has deepened, many Russian voices have boasted about an economic recovery and restoration of the country to its (allegedly) rightful place in global politics. They claim that Western sanctions have been a boon, helping the Russian economy shake off inefficiencies and hone its competitive edge.

Facts & figures

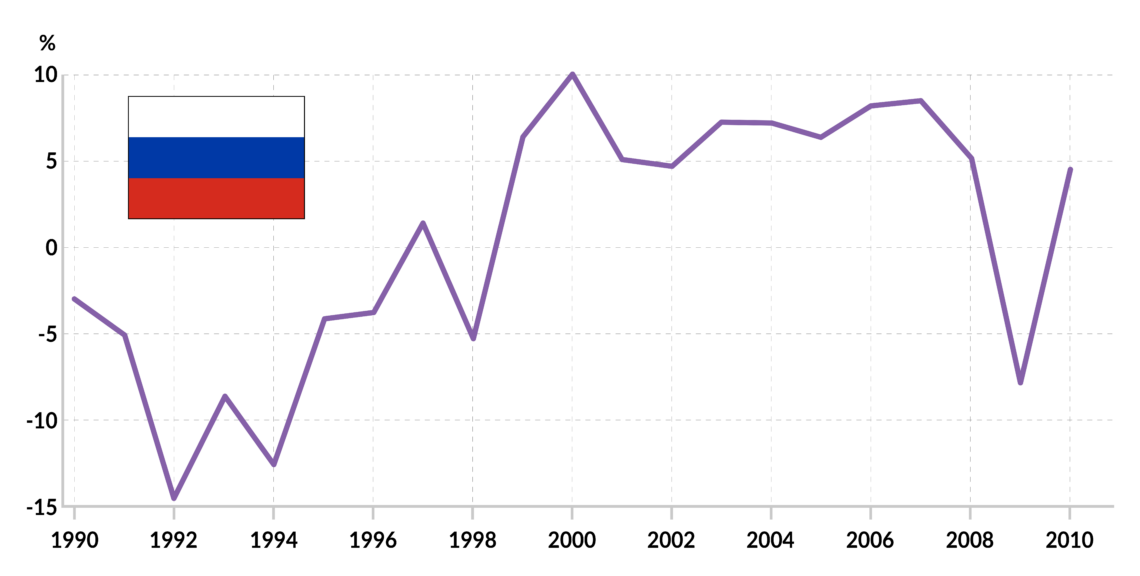

To appreciate just how hollow this argument is, recall Russia’s transition from central planning to a market economy. During the first two terms of the Putin presidency (2000-2008), the Russian economy grew by about 7 percent per year. This expansion was chalked up as a great achievement and credited to President Putin. The problem is that during the chaos of the 1990s, the Russian economy contracted by about 45 percent. It was only toward the end of 2007 that Russian gross domestic product (GDP) had again reached the level of 1990, showing that the country had lost close to two decades of virtually zero growth.

It was during these two decades that the Chinese economy took off. Meanwhile, Russia’s “recovery growth” did not produce the technological change nor the investment in critical infrastructure needed to support a leap into a modern, globally competitive economy.

This situation provides the baseline for any assessment of Russian prospects for global integration. While China has a powerful presence throughout value chains worldwide, the Russian economy remains focused on primary-sector development – digging, drilling and pumping. Except for Russia’s (already dwindling) energy supplies, there is little the world economy would miss if the country were to disappear.

Viewed against this background, the Kremlin’s pivot to Asia needed to boost foreign direct investment and achieve a transformation in trade flows. The exchange of raw materials for manufactured goods would be replaced by intra-industry trade that promotes knowledge transfer and human capital development. Neither has happened.

Theoretically, Japan could provide a significant boost, but businesses there have shown little interest in getting involved in Russia. South Korea could be another such source, but its recent agreement on an investment fund to support Russian-South Korean projects was limited to a measly $100 million by 2022.

Chinese interest has remained limited to energy flows and predatory logging, plus some ambitions to lease land. The hopes for investment spillover from the BRI have mostly sputtered. Russia has little but raw materials to offer China.

All this magnifies the dangers inherent in turning away from long-standing economic relations with Europe.

‘Independent pole’

When it comes to recovering its political influence, Russia had few genuine friends before the Crimea crisis, and even fewer thereafter. Countries like Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan have remained outside the EAEU, limiting Russian influence in Central Asia.

It is true that Russia has carved out a geopolitical niche for itself with its intervention in Syria. Having saved President Bashar al-Assad and his power structure – thereby thwarting United States’ ambitions to orchestrate yet another regime change – Moscow has become a hub of Syrian diplomacy. It has also managed to remain on good terms with most other regional actors, including Israel.

The Syria operation remains a sideshow for Russia to their principal, existential ambition of fostering a Greater Eurasian Partnership.

How long this will last is beside the point. Much like the intervention to prop up the regime of President Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela and the involvement of Russian mercenaries in Libya, the Syria operation remains a sideshow for Russia to their principal, existential ambition of fostering a Greater Eurasian Partnership. The central pillar of that strategy has been for Russia to emerge as an “independent pole” in Eurasia.

A quick survey of the geopolitics in the region shows that this vision lacked realism from the start. The regime in North Korea views China as the only pole conceivable. For South Korea and Japan, it is hard to see what they would gain from a more important Russia. Among countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Russia has a free trade agreement with Vietnam, but little nonmilitary trade with the other members. On the subcontinent, India resents Russia’s overtures to China. In Central Asia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are leading a charge to show that the region can solve its own problems without outside help.

The Greater Eurasian Partnership comes down to Russia securing a strategic partnership with China. For now, that relationship is neither strategic nor a real partnership. As veteran China analyst Bobo Lo suggested in a 2008 book, it is an “axis of convenience,” based on a common interest in blocking a world order dominated by the U.S.

Russian sources have begun to show signs of frustration, saying that despite “undisputed successes,” it may be “prudent to undertake a tactical pause” when it comes to the EAEU. There is good reason for the Kremlin to be concerned. Its belief in import substitution as a panacea stands in sharp contrast to the philosophy of connectivity driving the BRI. The sorry state of the Russian machine tool industry is emerging as a significant threat to military modernization. Simply remaining relevant to the rollout of the BRI will be an uphill battle.

This is the defining feature of the Sino-Russian relationship. While Beijing is happy to support the Kremlin’s pronouncements about how well the partnership is evolving, it has little to gain from helping Russia become an independent pole in Eurasia.

Scenarios

The strategic question before Russian and European leaders is whether a reset in relations is possible. There would seem to be plenty of reasons in favor. The cost to Europe from reduced trade has been substantial. Internal differences on how to deal with Russia have enhanced already deepening divisions between EU member states, while pressure to increase military expenditure is unwelcome.

Meanwhile, Russia faces the increasingly obvious fact that its only path toward proper integration into the global economy goes through Europe. Businesses from Germany and other European countries have stood ready to resume commerce and investment. Western energy giants have stood ready to resume the support for technology absorption that looked so promising before the sanctions. Financial markets would be only too happy to return to trading in Russian funds. A reset could trigger an economic revival that benefits both sides.

The obstacles are mostly emotional. On the Russian side, there is the old obsession with great power status and the associated demand to be treated with respect. European leaders, on the other hand, cling to the conviction that there can be no reset unless Russia first retreats and recants on Ukraine, which is not in the cards.

As Russia and Europe drift apart, Moscow is suffering a loss of influence on Eurasia’s western periphery. Georgia and Ukraine will not return to the fold any time soon, and even the much-vaunted union with neighboring Belarus has not yielded significant benefit. The outcome of the current crisis in that country may well be that Russia forces a consummation of the union, including rights to military bases. However, it would come at the price of incorporating an angry population that has shown its courage in standing up to repression.

Although it might seem evident that Europe could gain from resetting relations with Russia, it is more likely to remain supportive of U.S. sanctions policy. The fallout from the assassination attempt on Mr. Navalny has ratcheted up tensions even further.

The result will be further estrangement. As decline sets in, Russia will show its resentment by moving aggressively against NATO aircraft or threatening further military adventures. Meanwhile, China will have no qualms exploiting growing Russian weakness for its own gain.