A deep dive into Russia’s consumer market

Since the 2014 recession, Russian incomes have continued to decline, and with them the health of the country’s consumer behavior. Low-income households dominate, while wealth is far more concentrated in the hands of the rich than in other developed economies.

In a nutshell

- Russian consumers are mostly low income

- Most spend their money on the bare necessities

- A more “European” path of development could change things

Russia’s consumer market is unique for several reasons, and a look at its current dynamics can offer insight into where the country’s economy is headed. That, in turn, could have an important impact on its geopolitics.

To understand today’s Russian consumers, it is worth going back to the 1990s, when real incomes plummeted by more than 50 percent. The very next decade, the early 2000s, they rocketed by 260 percent, mainly due to the rapid rise in oil and gas prices. The result of this abrupt turnaround was a consumer boom unprecedented in Russian history.

Retail trade volume rose by a factor of seven between 2000 and 2010. The number of loans issued to individuals increased at an even faster rate. Most Russians were able to significantly increase consumption. Along with oil and gas production, domestic trade was a key driver of economic growth at the time.

In absolute terms, Russian households consume one and a half to two times less than their European counterparts.

Then, a recession hit in 2014, halting that real income growth and dragging it lower. Experts estimate that between 2014 and 2020, the drop was at least 12 percent. It is from this perspective that we will look at the current state of the consumer market, in terms of goods, services, housing and inequality.

Goods: Eating up income

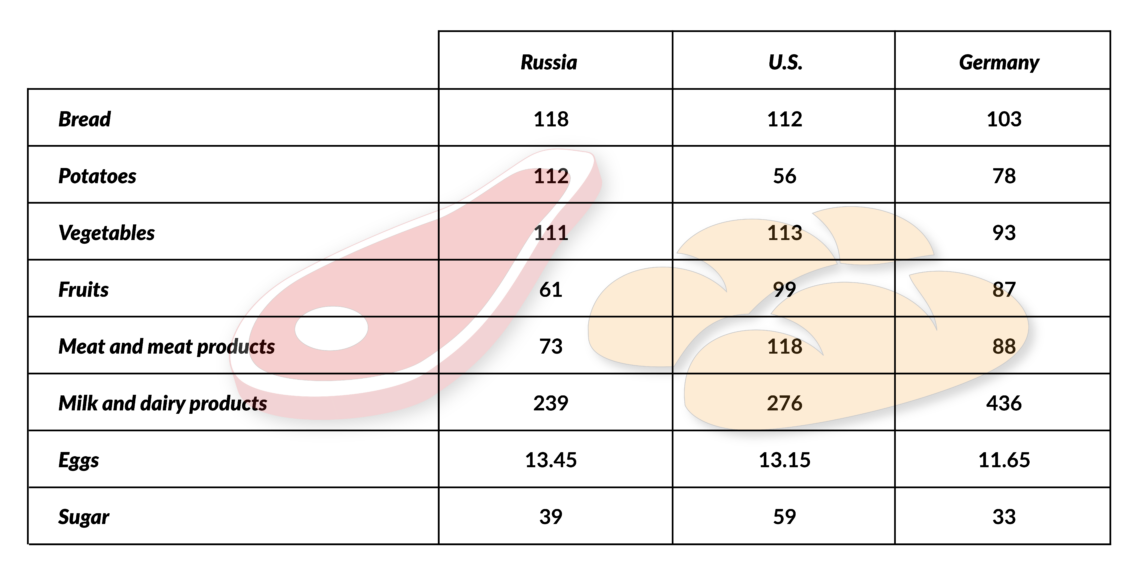

In 2020, household consumer spending accounted for half of Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP). By that measure, the country is similar to most in Europe. But in absolute terms, Russian households consume one and a half to two times less than their European counterparts. This raises the question as to whether a typical Russian household consumes less food, clothing, shoes, durable goods and services than an average European one (see table above).

Russia is not far behind in terms of total consumption of basic food products. However, there are two problems. The first is the significant lag in consumption of the most expensive food products – meat, dairy, vegetables and fruits – due to Russian households’ low level of income relative to developed countries, resulting in lower per capita GDP.

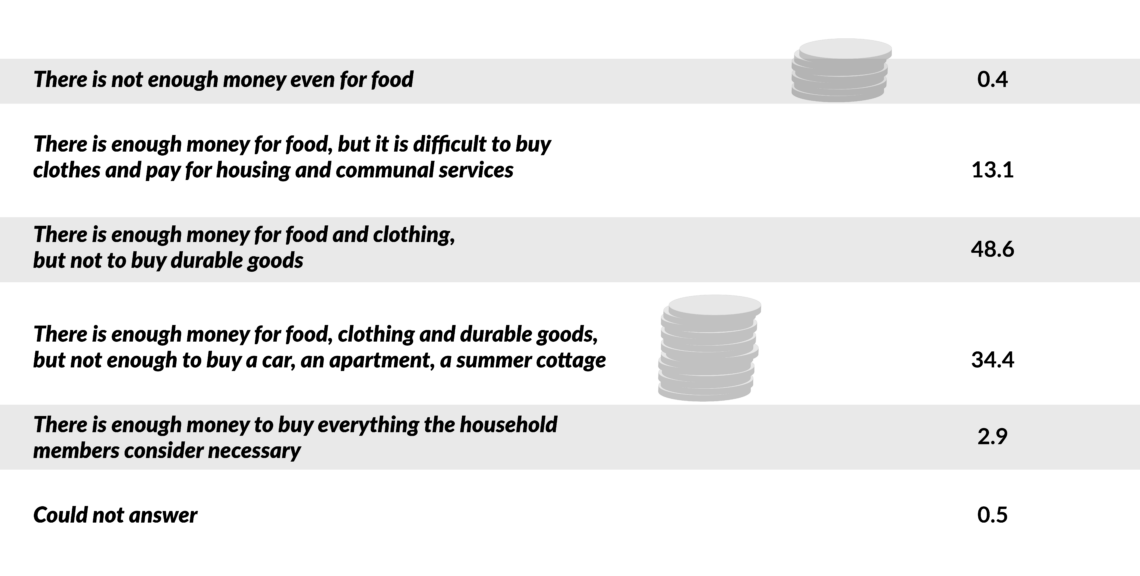

The low level of income also causes the second problem: food accounts for a disproportionate share of a typical Russian household’s expenses. In the fourth quarter of 2020, the proportion was 36 percent. Compare that to the 2019 data for the United Kingdom, where it came to 10.6 percent. In Germany, it was only 12.2 percent, in France 13.3 percent and in Poland 24.8 percent. This difference is a sign that many Russians remain without enough money to do much more than survive.

As a result, Russians purchase fewer nonfood goods and services. In the fourth quarter of 2019, according to a survey by the state statistics service, consumers described their economic circumstances as follows:

Facts & figures

Russian households’ low incomes mean they have fewer durable items that many in the West consider essential. At the end of 2019, only 40 percent of Russians had their own personal computer, while there were about 200 cars for every 1,000 people. In Germany, by contrast, 76 percent of people had their own personal computer, and there were 600 cars per 1,000 people.

Services: Low demand

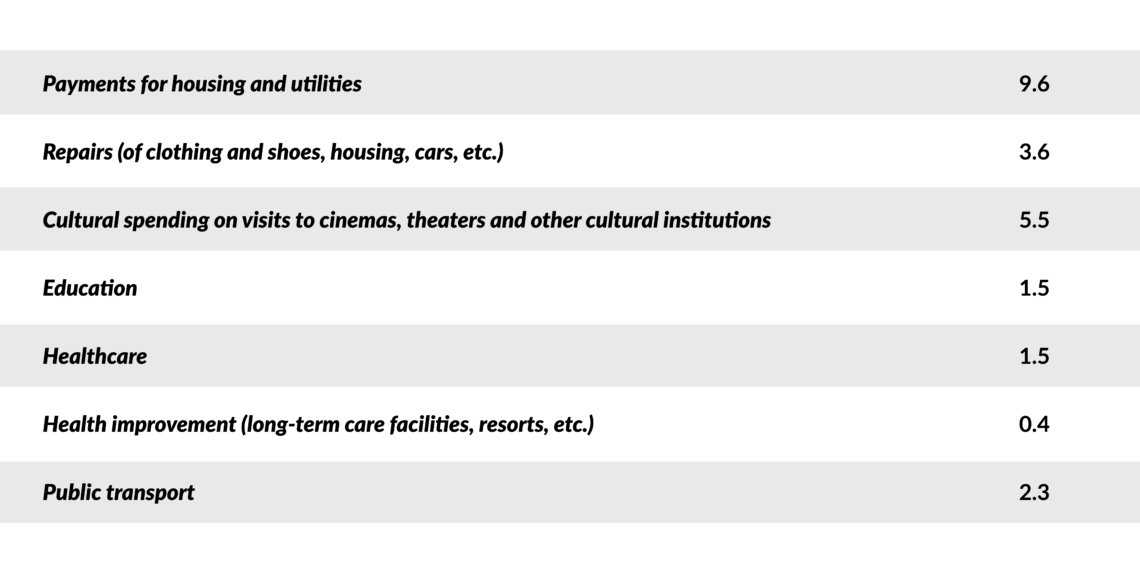

Now let’s examine the purchase of services. A typical Russian household spent 28.7 percent of its income on services in 2019, with the breakdown as follows:

Facts & figures

Here, it is worth considering some peculiarities of Russian social policy. Comfortable housing is significantly less available in Russia than in developed countries. In 2019, there were 25.8 square meters of comfortable housing per capita, compared to 39 square meters in Germany and 70 square meters in the United States. More than 30 percent of Russian houses do not have running water, sewage systems, natural gas or central heating. Meanwhile, subsidies to help pay for housing and utilities are widespread. These factors explain why Russian families spend less on such expenses than their Western counterparts.

Public schooling and some vocational education are free, as is public healthcare. Paid services in these areas exist, but there is little demand for them. The government subsidizes public transport, keeping ticket prices in check. Pensioners, disabled people and several other social groups are allowed to use public transport for free.

Moreover, low-income families save money by repairing their own clothes and shoes, cutting their own hair, and doing their own home repairs. This is especially common in rural areas, where 25 percent of Russians live.

Housing: Building up debt

Russia has a very peculiar history in terms of housing acquisition. During Soviet times, almost all urban housing, and much of the rural housing, belonged to the state. One of the reforms of the early 1990s was to privatize these assets. By 2000, some 47 percent of the total housing subject to privatization was handed over to private owners. By 2010 the figure was 75 percent, and by 2015 it was 79 percent.

Nevertheless, housing is less available and of lower quality than in the most developed countries. Some 44 percent of Russian families say they would like to upgrade their residence.

Since real incomes are declining, indebtedness is increasing.

In 2019, the average per capita annual income allowed for the purchase of only 6.8 square meters of new housing. To acquire their homes, Russians have turned to taking out mortgages. Between 2001 and 2018, about 9 million mortgage loans were issued. In 2020, due to the introduction of a preferential interest rate, a record 1.7 million mortgage loans were issued.

However, since real incomes are declining, indebtedness is increasing. The value of outstanding mortgages at the beginning of 2021 reached some 100 billion euros, of which about 1 billion euros was overdue.

Inequality: Low-income majority

Putting aside the average figures, Russian consumer behavior is remarkably diverse. As mentioned, low-income households predominate. They can barely make ends meet and buy only the most necessary goods and services. Among these are people who, according to official data, in 2020 had incomes below the “subsistence minimum” – some 12.1 percent of the population.

There is also a middle class in Russia whose consumption patterns are similar to the European standards of this social group. But, unlike its counterpart in developed countries, the Russian middle class is not large – no more than 15 percent of the population. At the same time, it is concentrated in the capital and other large cities, as well as oil- and gas-producing territories.

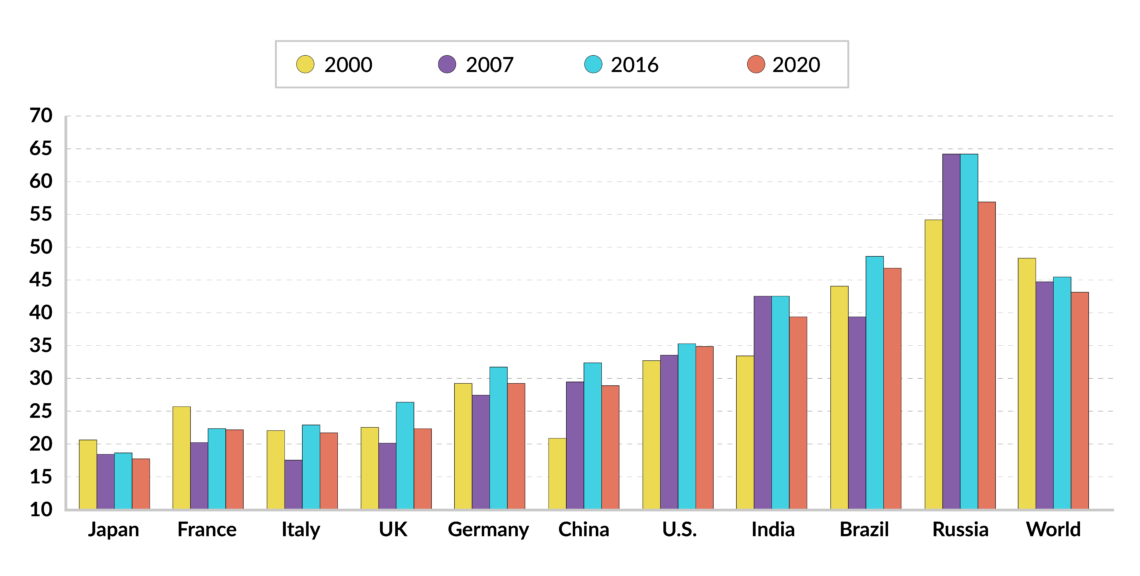

Moreover, Russia has high levels of income inequality. In 2018, the Gini coefficient (in which a number closer to 100 indicates higher inequality) was 37.5 in Russia, compared to 31.9 in Germany and 34.8 in the UK. The top 1 percent of earners account for a much larger share of the country’s wealth than in more developed nations, as can be seen below:

Facts & figures

It is these richest Russians who consume the lion’s share of luxury goods: expensive cars, jewelry, regular trips to restaurants, vacations at top resorts, and so on. And though they may be registered as residing in Russia, many of these people actually live abroad, where they have real estate, bank accounts and their own businesses.

The well-to-do population is concentrated in Moscow and the other large Russian cities with 1 million inhabitants or more: St. Petersburg, Nizhny Novgorod, Yekaterinburg, Novosibirsk, Kazan and Rostov-on-Don, among others. It is in these cities where most of the country’s retail infrastructure, such as large retail chains, can be found.

Scenarios

How Russian consumer behavior develops will hinge on several factors. The first is macroeconomic changes – for example, economic growth, inflation and tax policy. Another will be changes in government social policy, such as increases or decreases in pensions or public employees’ wages, as well as the addition or reduction of social benefits. Changes in Russia’s foreign policy, which could affect trade levels or how secure consumers feel, will also impact consumer behavior.

With all this in mind, two broad scenarios are possible.

In the first, Russia becomes more isolated internationally, while the economy (and with it, society) further degrade. The focus on basic goods and on ensuring survival will be magnified, while the health of the consumer market will suffer.

In the second, Russia returns to the European path of development, bolstering the economy and strengthening society. As this process unfolds, Russia’s consumer market will increasingly resemble Europe’s.

So far, Russia is developing along the lines of the first scenario.