Kadyrov’s Chechnya poses a growing risk for Putin

In Ramzan Kadyrov, Russian President Vladimir Putin has found someone who can both keep Chechnya under control and supply ruthless troops for conflicts in Ukraine and Syria. But the Kremlin’s hold over its Chechen warlord is tenuous and risks backfiring in the long term. Acting now could have dire consequences as well.

In a nutshell

- Ramzan Kadyrov provides stability in Chechnya and troops in Ukraine and Syria

- His growing strength is becoming dangerous for Moscow

- Dealing with Kadyrov now risks reprisals or war

- More support for him risks intra-Kremlin strife or a possible Chechen breakaway

As Russia’s March 18 presidential election approaches, the Kremlin is becoming increasingly worried that it may not be able to meet its target of a 70 percent turnout and a 70 percent vote in favor of President Vladimir Putin. There is no question who will be elected, but Moscow deems it necessary for political stability that Mr. Putin scores a decisive win.

This apprehension reflects how unevenly democracy has progressed in Russia. In big cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, the liberal opposition may still convince enough voters to abstain to make Mr. Putin’s victory seem unconvincing. Elsewhere, local leaders’ grip is such that the outcome is a forgone conclusion.

One such place is the Republic of Chechnya, which is formally a constituent part of the Russian Federation. In reality, however, it is an all but sovereign territory, bankrolled but not controlled by Moscow. In return for lavish subsidies from the federal budget, it can be expected to deliver a 99 percent turnout and a 99 percent vote in favor of the incumbent. For a president with strong authoritarian tendencies, this is rather convenient.

Pact made in hell

Closer consideration will show that the cozy relationship between the Kremlin and Chechnya has elements of a pact made in hell. Although federal subsidies cover about four-fifths of the republic’s budget, this does not translate into serious federal authority over the local ruler. In fact, there is plenty of reason for President Putin to be concerned.

The head of the Republic of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, is a self-styled Muslim strongman, supported by a private army of 30,000 combat-hardened former insurgents. The exact nature of his relationship with Mr. Putin is enigmatic. His extremely provocative behavior sometimes causes headaches in Moscow, but his increasingly prominent role in support of Russia’s intervention in Syria suggests how important he is to the Kremlin.

Behind a public facade of loyalty, Mr. Kadyrov is transforming his fiefdom into an authoritarian Islamic state.

Behind a public facade of loyalty and subservience, Mr. Kadyrov is transforming his fiefdom into an authoritarian Islamic state. He has introduced elements of sharia law, ranging from bans on alcohol and gambling to the promotion of polygamy, headscarves for women and segregated sports facilities. He encourages honor killings of women who break religious rules, sends clerics into schools to tell young boys to control their sisters, and is accused of gross human rights violations.

It is striking that Vladimir Putin’s presidency was born out of a war against the very same Chechens that he is now protecting. It was in response to an incursion by Chechen militants into the neighboring republic of Dagestan, in late summer 1999, that then-Prime Minister Putin launched a military assault on Chechnya that was prosecuted with extreme brutality. His ensuing war on terror would also be laced with harsh language against the Chechens. Yet, today he appears to be on the best possible terms with Mr. Kadyrov.

Interestingly, this former rebel commander can enjoy lavish subsidies and get away with outrageous challenges to the Kremlin’s authority. His record of rights abuses inside Chechnya probably does not cause too much heartburn among the security elites in Moscow, but those same elites normally take a dim view of regional leaders who play their games with the powers that be.

Moscow’s largesse

One reason why the Kremlin has allowed its warlord in Chechnya such a long leash goes back to the Chechen war. Grozny, the capital, was pummeled by the deadliest artillery and air bombardment in Europe since World War II and reduced to rubble. Having wrought immense destruction without suppressing the rebellion, the Kremlin was faced with the dual task of restoring order and rebuilding the country.

The former was achieved by recruiting Ramzan Kadyrov, who switched sides and proceeded to repress all rival groups. In 2007, when Russian federal forces no longer needed to worry about a threat from Chechnya, Mr. Putin appointed him head of the republic. The next year it was announced that $5 billion in federal funds would be spent to rebuild what had been destroyed.

Out of the rubble of Grozny rose a glitzy townscape marked by newly paved streets lined with high-rise buildings, slick cafes, sushi bars and beauty parlors, not to mention Europe’s largest mosque, named after Mr. Kadyrov’s father. There is even a boulevard named after Vladimir Putin.

Moscow’s largesse has been important not only in cementing Mr. Kadyrov’s stature as benefactor. Considerable funds have also flowed into his personal pockets, to cover the costs of a stable of race horses, a personal zoo with tigers and ostriches, and a $2 million Lamborghini Reventon. In 2009, the head of the Federal Audit Chamber, Sergei Stepashin, quipped that “the entire republic belongs to Ramzan Kadyrov.”

Troops for hire

Ensuring that Mr. Kadyrov maintains order inside Chechnya is not the only reason for the Kremlin’s patronage. Another is his sizable security forces. Formally part of the Russian Interior Ministry Troops, the fearsome Kadyrovtsy swear an oath of allegiance to Mr. Kadyrov, who himself holds the rank of Major General.

In case of serious trouble in Moscow, these troops can be trusted to fire upon Russian civilians. Mr. Kadyrov’s role as a Kremlin attack dog was brought home in the run-up to the March 2012 presidential election, when Moscow was shaken by huge rallies against the Putin regime. In a series of outbursts, he lambasted the organizers as jackals, hyenas and “enemies of the people.” His behavior was so outrageous that it galvanized civil rights defenders into demanding that action be taken.

Many hoped that once the Winter Olympics in Sochi concluded, it would be time for the Kremlin to deal with Chechnya. But it was not to be. The end of the Olympics coincided with the beginning of the crisis in Ukraine, which gave Mr. Kadyrov another chance to prove his worth. Some of the Russian troops that showed up on the battlefield in Donbas were Chechens.

Then followed the intervention in Syria, giving Mr. Kadyrov yet another opportunity. As non-Muslim troops on the ground would not be welcome, Russian support for Bashar al-Assad was mainly limited to the air war (and to mercenaries supporting the government forces on the sly). That constraint did not apply to the Kadyrovtsy.

Chechen police patrolling the streets in Aleppo looked good in the media and was much appreciated by the locals.

The dispatch of a Chechen police battalion to patrol the streets in Aleppo looked good in the media and was much appreciated by the locals. Offering to rebuild the Great Mosque of Aleppo added further to Mr. Kadyrov’s stature. The mosque needed repairs to the tune of $7 million. The Chechens took care not only of that tab, but also offered to rebuild the old mosque in Homs.

It was the story of Chechnya all over again. First the Kremlin assisted the Syrian regime in destroying Aleppo, which, much like Grozny, was reduced to rubble. Then Ramzan Kadyrov stepped in to take care both of restoring order and pouring millions into rebuilding what had been destroyed.

Scenarios

At a casual glance, it may seem that Mr. Putin has found a way of having his cake and eating it, too. But this ignores the potential downside. Looking forward, there are three possible scenarios for Chechnya, none of which should appeal to the Kremlin.

The first sees the Russian economy deteriorate to the point where workers take to the streets, causing a political situation where order must be restored by force. As Russian security forces could not be trusted to fire on Russian civilians, the Chechens could be brought in, as a Praetorian Guard to protect the president.

There is little to indicate that this is likely, but it is a scenario that plays into the evolving dynamic between the Kremlin and its supporters. A move to send in the Chechens would not only cause a crisis in relations with the Orthodox Church, it would also antagonize some of the security elites. They might be prodded into preempting such a development by staging a palace coup. Mr. Putin may therefore have reason to think twice about his cozy relationship with Mr. Kadyrov.

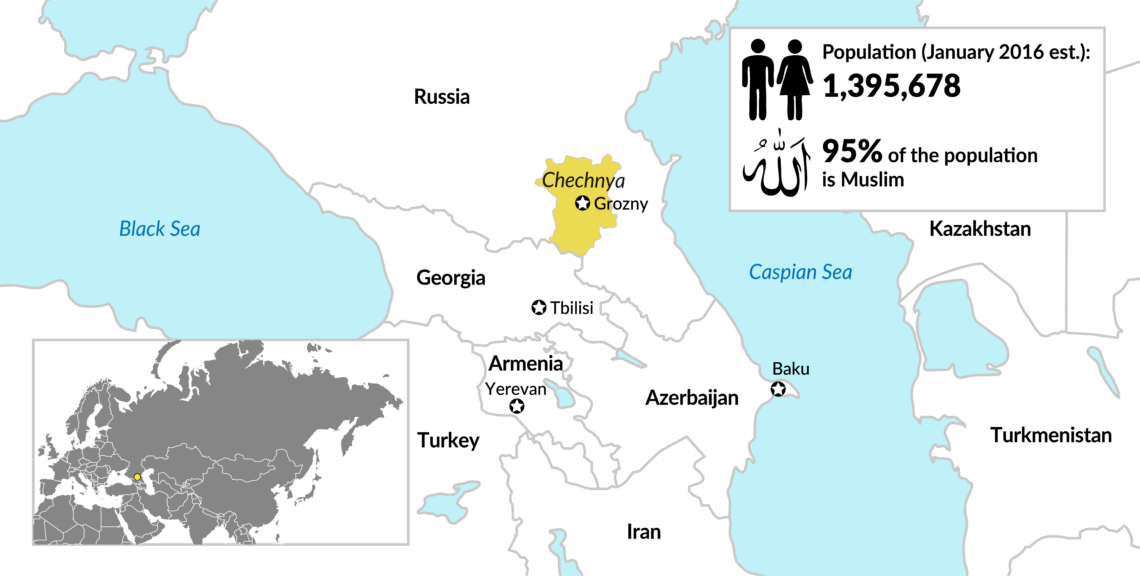

Facts & figures

Chechnya: Kadyrov's fiefdom

A second, opposite scenario is that Mr. Putin finally decides to do something to rein in his renegade warlord. He could simply cut off the flow of money, which would have a serious impact on Mr. Kadyrov’s ability to reward his cronies. It might, however, also trigger a forceful response. A string of terrorist incidents in Moscow and St. Petersburg would seriously undermine Mr. Putin’s standing as protector of the nation.

A more decisive move could be simply to eliminate Mr. Kadyrov. It would not be easy, but surely not beyond the ability of Russian special operations forces. The problem is that Mr. Kadyrov’s removal would probably reignite major armed conflict between the various Chechen factions, and the Kremlin does not need a third war in Chechnya, on top of its commitments in Ukraine and Syria.

The third and most likely scenario is more of the same. While this may seem appealing to the Kremlin in the short term, it also carries some rather serious implications for the longer term.

Muslim leader

Mr. Kadyrov’s repressive rule has already caused most non-Chechens to leave, and his promotion of sharia law is making its mark on a generation of young Chechens. This combination of ethnic cleansing and religious purification serves as an incubator for Muslim militants and a potential model for other radical leaders of the estimated 15 million Muslims residing within the Russian Federation.

Mr. Kadyrov is also pursuing a parallel foreign policy to enhance his standing in the broader Muslim world. He has hosted King Abdullah II of Jordan in Grozny and held talks with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. In 2015, the Saudi King even opened the Kaaba (the building at the center of the Great Mosque in Mecca, Islam’s holiest site) for Mr. Kadyrov and his entourage, a highly unusual move outside of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

In the eyes of fellow Muslim leaders, Mr. Kadyrov’s credentials are impeccable.

In the eyes of fellow Muslim leaders, Mr. Kadyrov’s credentials are impeccable. His Chechens have an established record as fearsome fighters. He upholds sharia law and lives up to the calls of Islam for charity. The Kadyrov Foundation, one of the wealthiest charities in Russia, has not only supported causes inside Chechnya, but has also sponsored the building of mosques in Israel and Crimea, and is doing the same in Syria.

Switching sides

In the short term, the Kremlin may feel its relationship with the Chechens is a winning game. At a time when Russia is on the side of the Shia forces that support the Assad regime, Mr. Kadyrov maintains good relations with the Sunni Muslim world, and especially with Saudi Arabia, which wants to see Mr. Assad gone.

The potential downside is that Saudi Arabia may use its friendship with the Chechens to extend its influence. There may come a time when a quasi-independent Islamic Republic of Chechnya, supported by Riyadh, unites with neighboring republics to realize the long-standing dream of many Muslim militants in the region: a caliphate in the North Caucasus. With Russia supporting Iranian-backed Shia forces in Syria and beyond, this would have some very interesting geopolitical implications.

Mr. Kadyrov has switched sides before, and Chechen factions have been fighting on all sides in Syria, including with Daesh (also known as Islamic State or ISIS). If he were to successfully rally all militants in a common break with Moscow, it would have implications not only for the Caucasus but also for Central Asia, which from the Kremlin’s point of view is a disaster waiting to happen.

The longer the Kremlin puts off dealing with Mr. Kadyrov and the rising role of Islam in Chechnya, the more it may live to regret its indecision. However, acting now risks producing such adverse effects in the short term that the longer-term threats may be more likely to materialize, with dire consequences.