Rwanda’s Paul Kagame faces challenges to legitimacy

Rwanda is often hailed as one of Africa’s brightest stories of growth and stability. But the pandemic and its aftermath present serious risks to the country’s economy. President Paul Kagame has taken a firm grip over Rwanda that might challenge his legitimacy.

In a nutshell

- Rwanda’s long-term growth has been strong

- The pandemic is taking a heavy toll

- President Kagame’s regime is more fragile

Rwanda is often pointed to as an African success story, an example of the continent’s renaissance. However, praise for the country’s record of economic growth and development comes with criticism of how the Rwandan regime deals with the opposition. As the country struggles with the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the legitimacy of President Paul Kagame and of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) regime will once more be tested.

Firm grip on power

The story of Paul Rusesabagina, the hero of the “Hotel Rwanda” movie, illustrates the complexity and contradictions of Rwandan politics, and how it is perceived abroad.

Mr. Rusesabagina saved 1,200 Tutsis during the 1994 genocide. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by U.S. President George W. Bush in 2005, and the Lantos Human Rights Prize in 2011. However, that same year, he was accused by Rwandan officials of financing the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, a rebel group that operates in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The group includes Hutu genocidaires among its ranks, and one of its goals is to defeat the RPF regime.

Most of those criticizing the regime are forced to operate from the outside.

In 2018, he was formally accused of terrorism, incitement to insurrection, arson and murder, and the Rwandan Attorney General issued an international arrest warrant. Mr. Rusesabagina, who lived with his family in Texas, was arrested in Kigali in August 2020, after being allegedly kidnapped in Dubai. The activist cofounded the Rwandan Movement for Democratic Change, a movement opposing the RPF regime that also had an armed wing, the National Liberation Forces.

Since 2007, the hero narrative around Mr. Rusesabagina was already being challenged by some Tutsi survivors and by the RPF regime. He had had become increasingly critical of President Kagame, claimed that he was the victim of an orchestrated campaign aimed at silencing him.

Facts & figures

Rwanda's Economy from A to Z

- GDP: 9.4 percent growth rate in 2019

- FDI: Up from $8.1 million in 2000 to $301.6 million in 2018

- SMEs: Over 55 percent closed in March-April 2020

- IMF: Granted $220 million in pandemic assistance

Paul Rusesabagina joined an extensive list of Rwandans who fell out of favor with the regime. These include RPF members like former head of security services Patrick Karegeya, who was murdered in South Africa amid mysterious circumstances; former cabinet director Theodore Rusadingwa; President Kagame’s former private secretary David Himbara; and the former vice president of the Supreme Court, Gerald Gahima. In 2010, Mr. Karegeya, Mr. Gahima and Mr. Rusadingwa issued a document accusing Paul Kagame of being a “corrupt dictator” and of turning Rwanda into “a hard-line, one-party, secretive police state with a facade of democracy.” Together, they created the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), an opposition group operating from outside Rwanda.

Given the legal and political restrictions imposed on opposition voices, those criticizing the regime – with a few exceptions, like the Democratic Green Party of Rwanda – are forced to operate from the outside. The regime, in turn, accuses groups operating outside the country of collaborating with armed rebels, thus posing an existential threat to the country’s peace and security.

Success story

Despite Rwanda’s particular conception of democracy – defined by the regime as a “consensual democracy” – and the systematic neutralization (including by force) of political dissent, Paul Kagame is often lauded in Africa and beyond as an example of sound leadership.

Two factors have contributed to legitimize the regime, despite its democratic deficits. First, the fact that Rwanda has achieved stability and peace (even if critics describe it as a “repressive peace”). Second, the fact that the Rwandan regime has been extremely efficient on the economic and developmental fronts. As former British Prime Minister Tony Blair put it in 2013, Rwanda was one of Africa’s biggest success stories, and a country which, despite a dependence on aid, offered “the best value for tax-payers’ money in the world.”

The overall progress in poverty reduction, health, and education is indisputable.

A landlocked and resource-poor country, Rwanda has made impressive economic and developmental achievements over the past two decades. In 2019, the country’s GDP grew by 9.4 percent, in line with an 8 percent average of the past decade – one of the world’s top reformers, according to the World Bank. Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows increased from $8.1 million in 2000 to $301.6 million in 2018.

While some experts contest official data, the overall progress in poverty reduction, health, and education – including a two-thirds decrease in child mortality and near-universal primary school enrollment – is indisputable. Moreover, these achievements are framed in an ambitious narrative, which sets clear goals and monitoring mechanisms, and emphasizes autonomy and accountability across all sectors.

Covid-19 impact

The effects of the Covid-19 on Rwanda’s prospects are mixed. While the country’s innovative paths toward universal health coverage have been highly praised, the system was not fully prepared to deal with the drastic increase in demand caused by a spike in Covid-19 cases.

Aware of this, the government focused on containing the spread of the virus and mitigating the pandemic’s effects on non-Covid health issues. This was done through a combination of highly sophisticated means, including the digitalization of surveillance and delivery mechanisms, the deployment of drones to deliver information and medicines to patients with chronic conditions, and the use of “anti-epidemic robots” to screen people for virus symptoms, along with a severe lockdown.

Between March 20 and April 30, all nonessential businesses and activities were halted. To mitigate the economic and social effects of the lockdown, the regime provided 20,000 families with food relief, eliminated taxes on mobile money transfers and launched an economy recovery fund worth 100 billion Rwandan francs. The fund focuses on the private sector and is meant to support the tourism, hospitality and conference industries (which expanded in recent years under the “Visit Rwanda” initiative), small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and individuals working in the informal sector.

Weaknesses and strengths

Given the weight of the services sector, which accounts for more than 50 percent of the country’s GDP and 25 percent of its exports, Rwanda has been severely affected by the disruption provoked by the pandemic. More than 55 percent of the country’s SMEs closed operations between March and April. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that GDP will contract by 4.2 percent, while the cost of the government’s response plan is estimated at 3.3 percent of the GDP – at a moment when the tax base has significantly narrowed.

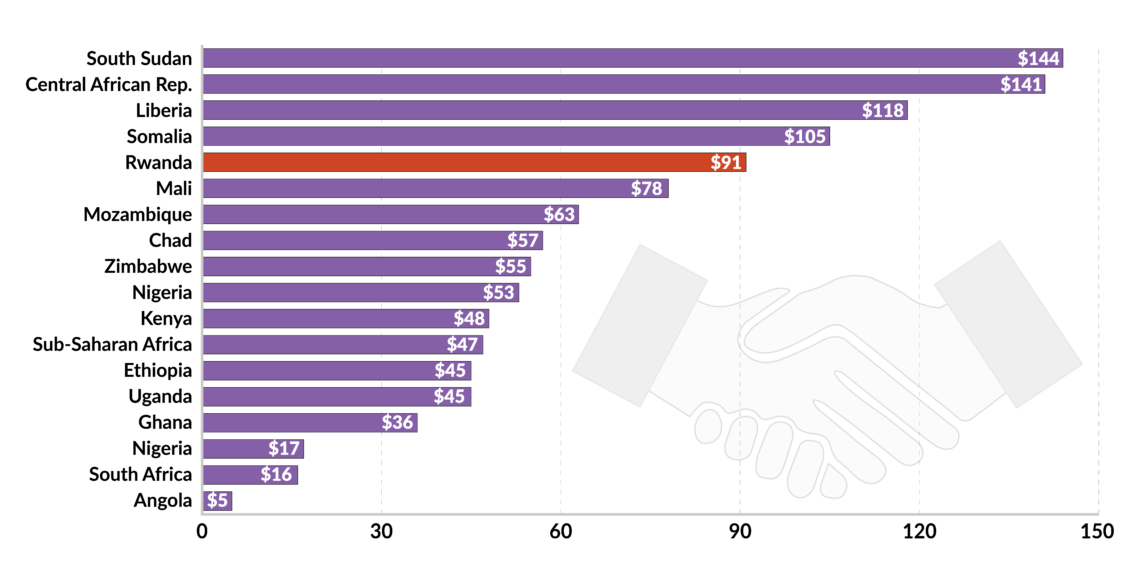

Aid dependency also contributes to Rwanda’s fragility. Despite a strong narrative of self-sufficiency accompanied by concrete efforts to move away from a reliance on aid, official development assistance (ODA) over the past several decades accounted for about 12 to 17 percent of Rwanda’s gross national income. In 2018, aid per capita was one of the highest in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), estimated at $91, while ODA accounted for 62.2 percent of government expenditures.

Facts & figures

Notwithstanding its overexposure to potential aid shocks, compared to other SSA countries Rwanda is less vulnerable to fluctuations in remittances, and more resilient to global FDI shocks. Moreover, the country’s reputation as an accountable partner and its efficient use of foreign aid have already had a positive impact. The government’s rapid reaction to the crisis by drafting a consistent economic plan as well as its positive debt-management record helped grant Rwanda access to $109.4 million in IMF rapid credit facility plus $111 million to support the balance of payments, as well as to an African Development Bank loan.

Scenarios

The economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemics directly hit one of the main sources of legitimacy for the Rwandan regime, at a time also characterized by greater awareness of Paul Kagame’s zero tolerance policy toward opponents operating from abroad. Two scenarios should be considered.

Under this first and most likely scenario, the Rwandan regime and its development model will be reinforced in the medium term. While the economic paralysis provoked by the pandemic severely hurt Rwanda’s poor, there are good reasons to anticipate a moderate recovery in 2021. Moreover, as indicated by the government’s response plan and clear future strategy, the country will likely emerge as an example of post-Covid recovery. Rwanda’s strong leadership, innovative approach to challenges (such as the use of cash transfers and mobile money for emergency assistance programs), and private sector-focused strategy have already garnered praise.

By stepping up as a post-pandemic success story, the Rwandan regime will increase its legitimacy at home and abroad. Moreover, recent trends – including rapprochement with Kinshasa and the progressive normalization of relations with Kampala – suggest that Kigali will remain a key regional player. The reassertion of Rwanda’s influence and its role in regional security, in a context characterized by chronic political instability and violence, will likely reinforce the country’s leverage with donors and international partners.

In July, a major obstacle to the improvement of French-Rwandan relations was removed, as a French court dismissed the case involving the attack against the plane carrying then-President Juvenal Habyarimana. Moreover, criticism and opposition to the regime will likely remain a mostly external phenomenon, as room for dissent inside Rwanda is minimal to nonexistent.

Under this second and less likely scenario, the economic and social impact of the Covid-19 pandemic would pave the way for the emergence of an internal opposition, while affecting the regime’s regional and international leverage and increasing the costs of political repression.

The persistence of the pandemic in 2021 would delay economic recovery and further punish the Rwandan services sector, particularly tourism. Aid dependency would become more salient, and ODA would likely diminish. Amid a protracted crisis, this could weaken the regime’s capacity to maintain much-needed investment and growth rates (public investment remains the main driver of growth in Rwanda).

Given the country’s recent history, the cooperative nature of Rwanda’s civil society and the absence of major opposition parties or figures inside the country, a scenario of popular protests remains remote. However, under this scenario the legitimacy of the RPF could be compromised, strengthening opposition groups operating in the region.