Pitfalls and dilemmas of arming Ukraine

Washington’s decision to sell modern U.S. anti-tank missiles to Kiev means that a red line in the West’s involvement in the Ukrainian crisis has been crossed.

In a nutshell

- Washington’s decision to let Ukraine have advanced U.S. anti-tank weapons has more political than military import

- Moscow is likely to respond by ratcheting up the military conflict in Ukraine and its pressure on the Baltic states

- The Kremlin is in a position never to allow having its proxy forces in the Donbas region routed

The long-standing issue of whether the West should supply lethal weapons to Ukraine gained a new twist on March 1, 2018, when, following lengthy internal deliberations and much pressure from the Pentagon, the State Department of the United States authorized the sale to Ukraine of 210 modern anti-tank missiles, the Javelin. It was a symbolically important step, signaling that the U.S. stood ready to increase its commitment to Ukraine’s cause.

Given dire warnings from various Russian sources against such a step, one would have expected a quick flare-up. On March 4, though, the Salisbury poisoning temporarily overshadowed the standoff over Ukraine. That does not mean the matter of the Javelins has been forgotten or forgiven. But the context has changed, in an alarming way.

As the Kremlin feels bound to retaliate for what it claims is unjustified ostracism for Salisbury, it is hamstrung by not having the economic muscle to respond in kind to tougher economic sanctions. Its response will therefore have to revolve around the use of force and threats thereof. Essentially, this means increasing Moscow’s political pressure on the Baltic states and ratcheting up the military conflict in Ukraine. The latter consideration should, in particular, inform any further debate on the merits of arming Ukraine.

Rhetoric and facts

In its official press release, the U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency claimed that the sale of the Javelins “will contribute to the foreign policy and national security of the United States by improving the security of Ukraine.” In a comment, Republican Senator Joni Ernst, member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, claimed the sale demonstrated that the U.S. is “serious about protecting the interests of our nation” and will help Ukraine “push back against growing Russian aggression.”

The sale of the Javelins offers a litmus test on whether providing Ukraine with defensive assistance is consistent with protecting U.S. interests.

The statements reflect two of the most contentious issues in the overall Western approach to the crisis in Ukraine. Is it really in the national interest of the U.S. to support Ukraine? And is it really possible to provide such support that Ukraine can push back against Russian aggression? The answer to neither question is clear-cut, but the evidence to date overwhelmingly suggests it is not affirmative.

Beginning with the national interest, there has been no shortage of voices pleading the case for providing Ukraine with, in the words of Republican Senator John McCain, “the lethal defensive assistance it needs to deter and defend against further Russian aggression.” The senator is arguably the most influential person in Congress on national security matters, his words carry weight. And his has not been a lone voice.

The case has been championed by such senior figures as John Herbst, the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine from mid-2003 to mid-2006, and Alexander Vershbow, deputy general secretary of NATO from early 2012 until October 2016. The chorus has also included Strobe Talbott, deputy secretary of state under President Bill Clinton, and several other diplomatic and national security luminaries.

Litmus test

Yet, while the Obama administration did agree to provide training and other forms of nonlethal military support, it stopped short of steps that might cause Russia to escalate its involvement. In its early days, the Trump administration followed the same path, authorizing sales of sniper rifles, scopes, and ammunition, but refusing to bend on sales of more advanced weapons. Now that the red line has finally been crossed, what will come next?

The sale of the Javelins offers a litmus test on whether providing Ukraine with “lethal defensive assistance” is indeed consistent with protecting U.S. interests. If the answer proves to be negative, then the outcome can only be a half-hearted battlefield escalation that increases the casualty rate but is easily met and repelled by the Russian side.

Above all, it brings into focus whether it is at all possible to provide enough support for Ukraine to successfully “push back against Russian aggression.” Although U.S. sources are careful in emphasizing that lethal weapons must be defensive, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko has made it clear that his ambition is to liberate Donbas. And his military muscle has been upgraded.

Facts & figures

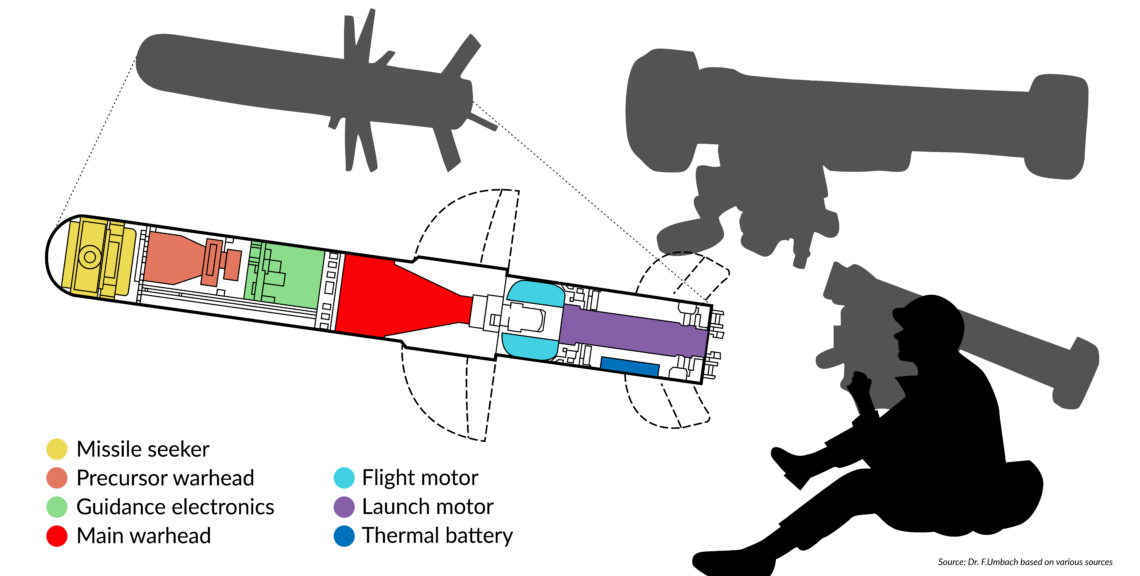

Javelin anti-tank missile, key components

The armed forces of Ukraine have nearly doubled in size since 2014, to about 250,000 men. The country’s arms manufacturing capacity is not to be taken lightly, and morale among the troops remains reasonably high. So, could added NATO support provide the edge needed to rout the Russian and Russian-backed forces?

Escalation ladder

The answer to that question was provided already in the spring and summer of 2014 when Kiev launched its “anti-terror operation.” Following the successful liberation of the rebel stronghold at Slovyansk, it did look like the insurgency would be burned out and that order would be restored.

Had the Kremlin refrained from interfering, there would not have followed some 10,000 killed, 1.6 million internally displaced persons, and vast material destruction, in the conflict since that time. But the Russian army did not stay out. It rolled across the border and shored up the insurgents, causing substantial casualties on the Ukrainian side.

The theater is also already saturated with Soviet-era anti-tank weapons that are effective against Soviet-era tanks.

As things now stand, the Kremlin is clearly not going to accept having its proxy forces routed. Those who oppose arming Ukraine are correct in noting that Russia owns the local escalation ladder. There is nothing that NATO can do that Russia will not be able to trump – until the level gets dangerously close to an all-out war between Russia and the West. And in the wake of the Salisbury atrocity, this danger is no longer academic.

Yet, matters are not quite that simple. The question of arming Ukraine must be viewed through a lens of what impact it will have on the political process rather than on the military conflict alone. This means that the choice of what weapons are delivered does matter.

Political angle

The Javelin is a potent weapon that attacks its target from above, where armor plating is most vulnerable. It would be lethal against the older versions of Russian tanks, and probably also against modern versions like the T-90 and the T-14 Armata. As the latter is equipped with Relikt reactive armor, and with disruptors that may destroy incoming missiles before they strike the tank, the effectiveness of the Javelin has been debated. A matchup would, in consequence, have a considerable commercial export angle. But it is not overly relevant to the situation on the ground.

Tanks did play a role in the May 2014 Russian effort to capture the airport at Donetsk, and to stabilize the front line. Once the latter had been achieved, though, they were reduced to a rather ineffective mobile artillery. The theater is also already saturated with Soviet-era anti-tank weapons that are effective against Soviet-era tanks.

Providing Javelins to the Ukrainian forces might have the effect of deterring the Kremlin from deploying modern tanks in an armored westward push. But this presumes that such plans are being considered. All available evidence suggests that, to date, the Russian side has been quite happy with maintaining a low-intensity “frozen” conflict. Beyond sending a signal that Washington is ready to up the ante in Ukraine, the 210 Javelins will do little to change the actual course of the conflict.

Moreover, this is an expensive weapon. At $80,000 per missile alone, it will typically cost more than the targets it eliminates. But the same logic applies to sending Tomahawk cruise missiles to destroy empty storage sheds, so this may not be very relevant.

Artillery, stupid

What is relevant is that the primary weapons used in Donbas have not been tanks and anti-tank missiles, but old artillery systems. The bulk of the casualties have been caused by multiple rocket launch systems that date back to the 1980s. There is nothing very smart about this. Drones are being used for targeting, but not for precision strikes.

If reducing the daily grind of killings were the West’s objective, the discussion would have focused not on tank killers, but rather on satellite intelligence, targeting drones and counter-battery radars. Upgrading this capability would make much more sense than providing the expensive Javelins. It would also have an important impact on the political process. Reducing Ukrainian vulnerability to indiscriminate artillery shelling would weaken Moscow’s bargaining position.

Even in such a scenario, though, improving the Ukrainians’ ability to target Russian artillery positions may not be so easy. This was shown after a Ukrainian artillery officer developed an application for Android smartphones that allowed gunners to process targeting data more quickly. Russian hackers, believed to be from the GRU “Fancy Bear” team, quickly succeeded in uploading malware that allowed the Russian side to track the movements of Ukrainian artillery units. This form of cyber warfare is yet another dimension of the conflict where the Russian side has a clear edge.

Russia, China, and other actors will be able to acquire specimens for study and testing.

Ukrainian forces also have to deal with Russian artillery firing with impunity from the Russian side of the border. Striking those positions would entail an open declaration of war – reflecting how costly for Ukraine the West’s acceptance of the Kremlin’s preposterous claim of noninvolvement has been.

Reform deficit

Perhaps the most important downside to the case for “arming Ukraine” is that it begs the question of who the actual beneficiary will be. The U.S. does have ample bad experience of sending weapons and equipment into zones of conflict where it is not clear who is who. Some of the war material sent to Syrian rebels likely ended up in the hands of the so-called Islamic State – also known as Daesh, or ISIS.

Given the notorious corruption of the ruling elites in Ukraine, one must realistically assume that parts of potential weapon deliveries will end up on the black market and that Russia, China, and other actors will be able to acquire specimens for study and testing. To this may be added that providing modern weaponry will not be very useful unless officers and their troops are properly trained in operating those weapon systems.

The latter is a sore point. Despite much talk about military reform, that process is not getting off the ground in Ukraine. As the top military brass remains reluctant to change their ways, much-needed transformation in leadership and in operating procedures is not happening. One consequence is that while NATO instructors may be effective in training Ukrainian recruits in the arts of modern warfare, six months later those recruits become demobilized and the process has to start from the beginning.

Scenarios

The real danger lies in triggering a scenario of escalation where both sides act on emotion rather than coolheaded strategy. It could take the form of a defiant Russian drive to take Mariupol on the Azov Sea coast and continue to link up with Crimea over land. This is where Javelins would be useful indeed, and where other modern weapons supplied by the U.S. would also have to come into play.

It could also take the form of the Ukrainian forces making a move against the separatists, believing that the U.S. would cover their back. That would prompt Moscow to stabilize the separatist positions by surging its own regular forces in Donbas.

In either case, we would no longer be faced with 1980s warfare, but a conflict with increasing commitment of modern weapons systems, possibly including air force. Given that the Kremlin’s main political asset in the conflict has been its deniability of being involved, Russia may be expected to shy back from an escalation that would make its involvement all too obvious. The risk involved for the U.S. is that failure to respond forcefully to a Russian escalation would effectively signal that the rhetoric about a national interest in standing by Ukraine has been little more than posturing.

Combining the latter two points suggests that serious escalation is not likely. Both sides would risk being drawn into an uncontrollable spiral of having to commit forces way beyond what a month ago may have seemed totally unacceptable. A permanent freeze of the conflict thus remains the likely scenario, even with some escalation in U.S. weapons support. Yet, under the present circumstances, a process that spirals out of control can no longer be ruled out.