The lost promise of South Africa

Africa’s second-largest economy is struggling. The long-dominant African National Congress party will likely pay the political price as discontent rises.

In a nutshell

- Corruption and economic mismanagement have eroded public confidence

- High poverty, unemployment and crime are fueling societal unrest

- Alternatives to the African National Congress have their own problems

Since 1994, the African National Congress (ANC) has been the dominant party in South Africa, winning five successive elections, appointing five presidents and, with few exceptions, controlling national, regional and local politics.

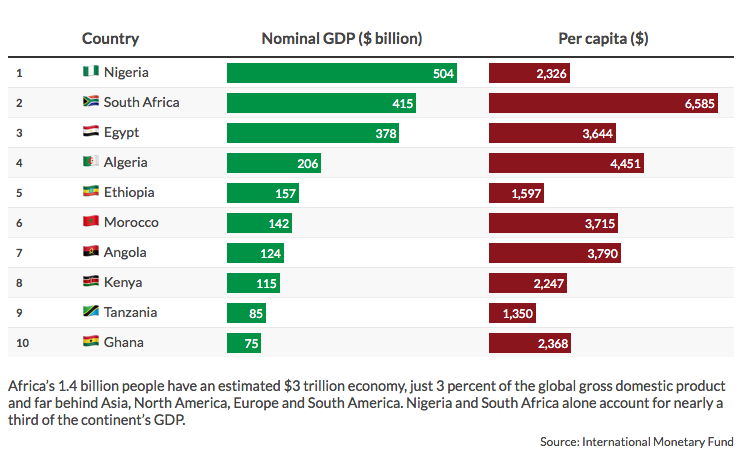

While the end of apartheid and the establishment of democracy are seen as irreversible, the nation of nearly 60 million people – with Africa’s second-largest economy after Nigeria – may soon enter a new and uncertain political era, in which the ANC is no longer the dominant political force.

Failed expectations

The postapartheid period was characterized by high expectations. With the transition to majority rule, the nation sought to achieve its economic potential by creating equal opportunities for all South Africans. But after peaking in the 2004-2007 period, the economy has encountered challenges and setbacks. These were accompanied by major corruption scandals and perceptions that the regime was failing to fulfill its promises of prosperity.

In 2008, after nine years in power during which the economy grew on average 4.2 percent annually, President Thabo Mbeki resigned at the request of the National Committee of the ANC, a decision that was subsequently ratified by the National Assembly, where the party held a two-thirds majority. The removal of Mr. Mbeki illustrates the tensions within the ruling party, between those who defend the compromises of Nelson Mandela, who promoted racial reconciliation, and a more populist faction represented by Jacob Zuma, who became president in 2009, promising to undertake “radical economic transformation.”

Under Mr. Zuma, the country experienced its first postapartheid era recession because of unfavorable external factors, unsound economic policies and high levels of corruption. The country has not escaped a vicious cycle of lackluster growth, persistent high poverty, rising unemployment and worrying crime statistics. Facing a criminal case, Mr. Zuma was recalled by the ANC executive committee and eventually forced to resign in February 2018. He was succeeded by Cyril Ramaphosa.

Also on South Africa

Rifts deepen in South Africa

Ramaphosa struggles with economic issues

Despite his efforts, President Ramaphosa is failing to revive the economy. Growth is modest (roughly 2 percent in 2022), and the economy was severely hit by the pandemic. Lockdowns were particularly harmful to South Africa’s urban poor.

Fiscal pressure is overwhelming, amid increases in civil service employment and pay and the expansion of social grants. The payments go to over 30 percent of the population but have not decreased poverty. High unemployment also signals the malaise of the South African economy. In the last quarter of 2022, the unemployment rate was estimated at 32.7 percent, and even higher among youth.

Another worrying symptom, which became more evident since the Zuma presidency, is the failure of South Africa’s state-owned enterprises, beset by corruption, financial mismanagement and inefficiency. The detrimental effects became evident in cases like Transnet, the state railway company at risk of collapse, and Eskom power utility, which supplies 90 percent of the country’s electricity. President Ramaphosa was recently forced to declare a state of disaster to address persistent electricity shortages, which he described as an “existential threat to the economy and the social fabric.” Eskom is technically insolvent and struggling with outdated infrastructure as well as corruption. On April 1, electricity fees increased by 18.65 percent.

The current energy and economic crisis is both a consequence and cause of rising political and social tensions, as evidenced by the 2021 riots and the recent national shutdown convened by the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters party (EFF). Such tensions are aggravated by the ongoing discredit of the political class, fueled by scandals like the theft of pandemic protective equipment by the national police.

Facts & figures

The ANC’s crisis of legitimacy and what comes next

While the ANC is going through a deep crisis, it is far less clear what an alternative to the current status quo could look like. Although the party won the 2019 general elections with 57.5 percent of the vote, electoral support for the ANC has been declining since 1999. Whereas the ANC is not the only actor in South Africa’s political landscape, none of the other parties seems to offer a viable alternative.

Since 1994, the Democratic Alliance (DA) has been the main opposition party. The party’s political origins are connected to the anti-apartheid movement and the DA has offered a liberal and post-racial approach to politics. However, a combination of historical and circumstantial factors has reinforced the idea among large segments of the electorate that the DA essentially represents the interests and concerns of white South Africans.

The party, which secured 20.7 percent of the vote in the 2019 elections, has already been tested as a political alternative in the Western Cape Province, where it has been in power since 2009. The Western Cape, also known as Silicon Cape, differs in many respects from other provinces in South Africa. Movements have been advocating for a Capexit, i.e., calling for a referendum on Western Cape independence, a move which, according to advocates, is supported by 58 percent of the voters in the province.

But, since 2019, the DA has lost several prominent figures, especially young black leaders who accuse the party of losing its appeal by focusing more on white identity than on building an alternative to the ANC. Mmusi Maimane, who was the leader of the DA between 2015 and 2019, left the party and founded the Build One South Africa (BOSA) last year, an “umbrella organization” for independent candidates, and announced his intention to run for president in 2024. Herman Mashaba, former mayor of Johannesburg, also abandoned the DA to create a new party, the ActionSA. Like BOSA, ActionSA denounces a broken system and calls for structural changes, adopting a liberal and post-racial political perspective.

After the ANC and the DA, the other main party of South African politics is the EFF of Julius Malema. The EFF is a radical party, which competes with the ANC for some segments of the electorate. The party, which was founded in 2013, made significant gains in the 2019 elections, securing 10.8 percent of the vote.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

As South Africans are faced with energy and economic crises, and the support for the ANC erodes, the 2024 elections may signal the beginning of a new political era, one in which leaders inside and outside the ANC will be forced to make difficult choices. Four medium-term scenarios should be considered.

Fragmentation

Under a first and more likely scenario, the end of ANC hegemony will give way to fragmentation and polarization. Under this scenario, votes would be more divided across the political spectrum. Ideological cleavages (primarily nationalism vs. liberalism) would increase. In this context, coalition politics would become the rule, but forming a stable ruling coalition at the national level would be very challenging.

Political instability, in turn, would adversely impact the already negative economic outlook. In the absence of rapid and deep reforms, South Africa would lose its demographic window of opportunity. The share of the population living in poverty, which is already over 50 percent, would continue to increase. This scenario could accelerate the erosion of social cohesion, and lead to higher levels of insecurity. In the long term, the country could lose its regional power status.

The end of the Mandela compromise

Under this scenario, the end of the ANC hegemony would result in an informal ruling coalition between the ANC and the EFF. While this is a slightly less likely scenario, it could result from a combination of two factors: the predominance of the more populist Zuma faction within the ANC; and the electoral success of the EFF, if it secures enough support to become the junior member in a coalition with the ANC. Whereas parties and leaders, especially populist ones, tend to moderate their positions once in power, this allegiance would have economic consequences. The nationalization of banks and mines, as well as land expropriation without compensation, would be put on the table.

This scenario would lead to the end of the Mandela compromise and the 1994-1996 constitutional settlement. Based upon liberal democracy and pluralism, this settlement has been criticized by some African nationalists, who favor the model of Zimbabwean revolutionary and leader Robert Mugabe. Moreover, this scenario would also increase polarization and could reinforce separatist claims such as the ones advanced by Capexit.

Reform

Under this least likely scenario, the erosion of the ANC’s standing would pave the way for structural (and painful) reforms, including the privatization of state companies, a more flexible labor market, restructuring of the energy sector and greater infrastructure investment. Such reforms are essential to ending the current stagnation of high debt, rising poverty and unemployment, as well as poor health and education services. Under this scenario, South Africa could benefit from its competitive advantages, including a diversified and digitalized economy and a sophisticated financial system.

The ANC during the Mandela and Mbeki eras had a reformist impetus. However, the party has been taken over by factionalism and does not have the incentives to unleash reforms, especially when politics has become more competitive. The policies promised by the EFF, in turn, are more radical than reformist. And whereas both the DA and several nascent parties are committed, at least in their manifestos, to such reforms, they are not expected to form a ruling majority in the short to medium term.

Business as usual

Under this scenario, the ANC would remain dominant. Securing a new term combined with external and domestic pressures could encourage President Ramaphosa to undertake important reforms. But factionalism within the ANC would likely remain an obstacle. This scenario may happen in 2024.