South Africa’s Russian ties come under scrutiny

While South Africa, a leader in a 16-nation regional association, proclaims neutrality in Russia’s war on Ukraine, critics say its actions support Moscow.

In a nutshell

- A test looms over how Pretoria navigates an arrest warrant against Vladimir Putin

- South Africa’s free-trade privileges may be at risk if the nation violates U.S. sanctions

- The alleged shipments of arms to Russia triggered a scandal and investigation

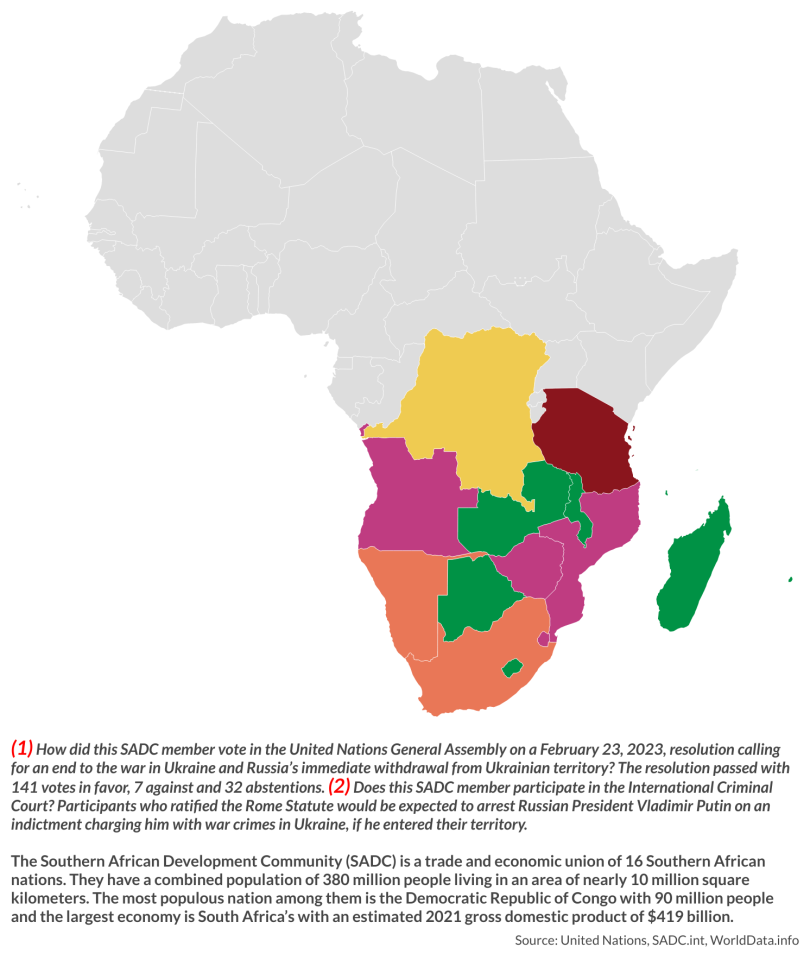

Southern Africa’s relationship with Russia amid the Kremlin’s war on Ukraine is difficult to discern. Since the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022, the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), a trade and economic union of 16 countries, has assumed a neutral position.

While some member states are committed to not taking sides, South Africa is a different story. The regional powerhouse of 60 million people, with Africa’s second-largest economy, has a cozy relationship with Moscow even as Pretoria claims neutrality.

Earlier this year, South Africa hosted Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and participated in military drills with Russia as part of a series of events coinciding with the anniversary of the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine. This has had diplomats in Pretoria scrambling to defend such actions. President Cyril Ramaphosa also put forward a peace initiative in which he and other African leaders visited Kyiv and Moscow on June 16-18 and met respectively with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Facts & figures

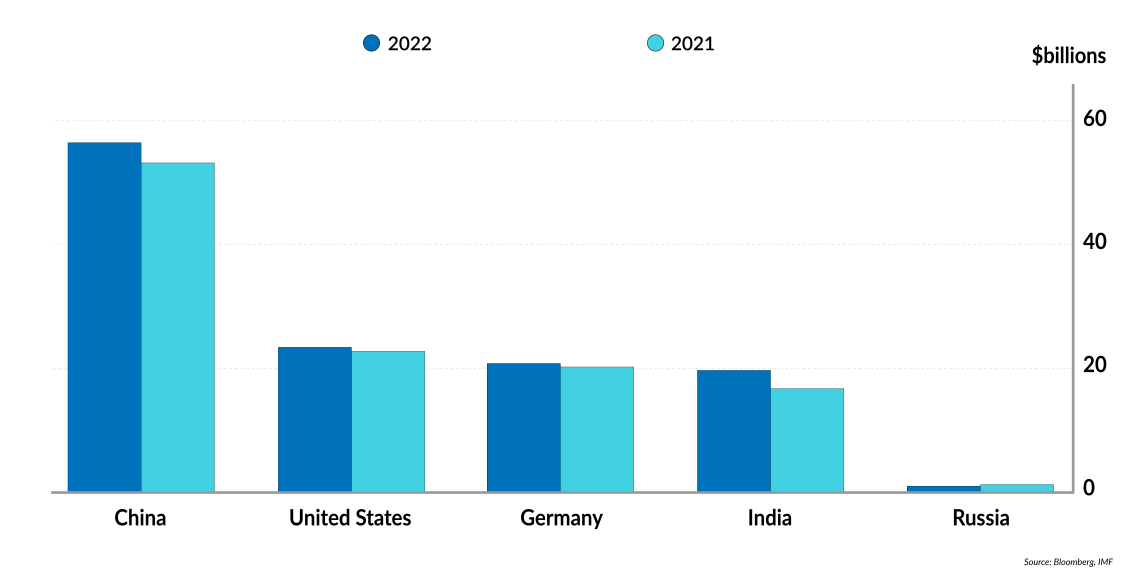

South Africa’s top trading partners do not include Russia

Pretoria was accused of supplying Russia with weapons

South Africa’s true intentions came under further suspicion when United States Ambassador Reuben Brigety in May accused Pretoria of loading weapons and ammunition on a sanctioned Russian vessel docked at Simon’s Town naval base near Cape Town in December 2022. The government initially denied the allegations and claimed that Ambassador Brigety had apologized for his public statement. However, due to both local and international pressure, the government launched an independent investigation into whether arms and ammunition were being sent to Russia on the vessel.

South Africa’s governing party, the African National Congress (ANC), has its hands full as the Russian crisis is becoming controversial domestically, adding to the woes of a party that struggling to deliver services to the nation and address the scourge of corruption that has engulfed the country’s politics.

In the middle of parliamentary discussions about whether South Africa had supplied arms and ammunition to Russia since the invasion, it was confirmed that the commander of South Africa’s ground forces, Lieutenant General Lawrence Mbatha, went to Moscow on an official visit. This fueled even more public mistrust of the ANC-led government. Civil society organizations and activists in South Africa have also ramped up criticism of the government for clinging to a nonaligned position that they argue runs against national interests.

Putin risks arrest if he comes to South Africa

In addition, South Africa invited Mr. Putin to visit in August to attend a BRICS summit, the association that fosters closer ties among Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The welcome came despite the arrest warrant of the International Criminal Court against Mr. Putin for his government’s allegedly forcible deportation of Ukrainian children during the war. Even with the government insisting that President Putin can attend, the possibility of a court petition by local civil rights organizations to compel Pretoria to arrest President Putin is real. Former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir’s visit to a 2015 African Union summit held in South Africa sparked petitions by civil society organizations, with the courts concluding that South Africa had an obligation to arrest Mr. Bashir. Policymakers in Pretoria are fully aware of the potential fallout with hosting Russia’s leader in South Africa, yet they persist in extending the invitation.

South Africa’s posture will remain controversial if Pretoria is willing to ride out the storm, even in the face of disapproval from other SADC member states. South African support for Russia could also bring economic consequences if secondary sanctions are imposed or trade privileges revoked, such as under the African Growth and Opportunity Act in the U.S., which grants duty-free terms to specific nations.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

The SADC is divided about the meaning of nonalignment in relation to the Russia-Ukraine war. This has been seen in the United Nations General Assembly debates on the conflict, with SADC countries struggling to balance human rights concerns and regional implications. This war is a test of the practical ramifications of nonalignment on a complex foreign issue that has become a domestic political concern.

Pretoria’s insistence on a business-as-usual relationship with Russia despite the invasion is a difficult position.

Since the invasion, the regional SADC position has been confusing. Other member states in the SADC could begin to engage South Africa on the regional harm caused by Pretoria’s friendliness with Moscow.

The coming BRICS summit in South Africa is scheduled for August. Because of the arrest warrant against Mr. Putin, it will test how far South Africa is willing to go in defying Western nations and its own ICC commitments. South Africa’s ex-president, Thabo Mbeki, has voiced concerns about whether the summit will go ahead at all.

In South Africa, the judiciary has been brought into the fray as civil society organizations test various aspects of the government’s position on Russia, including the consequences of failing to execute the warrant on President Putin.

This will continue to create political headaches for the ruling ANC. More countries in the region, including Botswana, may find it necessary to distance themselves from South Africa to preserve the broader relationship with Western societies. The SADC position will become even more awkward unless the chasm among the 16 member states is bridged.