Argentina: Macri yet to score on economic reform

The government of Argentina can chalk up its first modest successes in improving a badly distorted economy. But the peso’s recent bad run against the dollar has signaled there are limitations to President Macri’s play it by ear, gradualist approach to reforms.

In a nutshell

- Argentina’s gradual economic reform takes longer to produce results than its government can afford to wait

- Hosting a G20 meeting in late 2018 was supposed to give Argentina a showcase for its global ambitions

- Instead, an abrupt weakening of the peso spells new economic and political trouble

When Mauricio Macri became president of Argentina in January 2016, he promised to “return Argentina to the world” and remove the distortions crippling its economy. The president meant to restore Argentina as an effective member of the international community and make it a global player in the positive sense – the very opposite of what his predecessor, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, had brought about.

This was a necessary prelude to Mr. Macri’s primary goal of putting the nation’s economy back on track. The new leader got off to a promising start when his team resolved outstanding disputes with bondholders who had claims against the Argentine government following its default in 2001. The settlements with these creditors opened the door for Argentina’s return to the international financial markets. The government also ended currency exchange controls and reopened the national statistics office, which Ms. Kirchner had shut down in 2014 to avoid publishing embarrassing consumer price data.

Showcase event

President Macri’s boldest effort thus far, also successful, has been to win the role of host for the November 2018 G20 meeting, which will be held in Buenos Aires. Members of the G20, who will meet for the first time in Latin America, are a mix of the world’s biggest developed and emerging economies. At least 45 meetings of various Argentine ministries and groups are planned to prepare a final agenda for the event. The author of this report had the privilege of participating in one of these preparatory discussions, called Think20 (T20), in February. The gathering brought together academics and representatives of think tanks and NGOs from around the world to debate agendas and prepare papers for the heads of state on a wide variety of issues.

The Macri government is faced with economic and political challenges that can rain on its parade in November.

President Macri wants the G20 meeting to showcase Argentina’s ability to help set the global agenda. At the same time, he is pushing ahead with his country’s application for membership in the OECD. That is proving more difficult, because of Argentina’s wide fiscal deficit, high inflation and a politicized judiciary inherited from the Kirchner government. At the end, the application is likely to be delayed.

Putting on an international gathering like the G20 is a major logistical and political task for any state administration. At the same time, the Macri government is faced with economic and political challenges that can rain on its parade in November. How the president handles these challenges, especially the financial markets’ lack of confidence showed by a run on the peso in early May, will have a major impact on Argentina’s ability to act in the global community. To deal with the currency crisis, the Macri government had to call for help from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Such signs of vulnerability may hurt Mr. Macri’s chances for reelection in 2019.

Economic shambles

Two and a half years ago, the president and his team inherited an economy held together by loans and subsidies that were financed by printing money. The public-sector fiscal deficit and inflation were surging. The state bureaucracy had been expanded by more than 2 million new, underutilized employees who swelled the national, provincial and municipal administrations. More than 3 million new retirees who had never contributed to the social security system were brought under its umbrella – with all the obvious financial consequences. Fees for public services had been held at artificially low levels, leading to stagnant investment in the country’s energy system, deteriorating public transport and crumbling infrastructure.

The result was market distortions and rising inflation (consumer prices surged 45 percent in 2016) that hurt Argentina’s global competitiveness. While in power, Ms. Kirchner shut down the nation’s statistical office, INDEC, so she wouldn’t have to look at the economic mess she had made. Mr. Macri put INDEC back in business and now must ensure that its indicators satisfy his economic and political constituencies. That is a very tall order.

Domestic strategy

After settling with the bond holdouts, the key decision the president took with his team was adopting a gradualist rather than a shock-treatment approach to economic policy. The reformers concentrated first on winning back investors’ confidence in the strength of their program and pro-market credentials. They reasoned that injecting capital into the Argentine economy would spur production, boost exports, build up tax revenue and allow the government to wean itself off constant borrowing. These welcome developments, the plan went, would expand real employment, allowing the government to trim the bureaucracy without disrupting the labor market or causing political fallout.

The Macri team’s big challenge was to strike the right balance between interest rates, inflation, the peso’s exchange rate, the fiscal deficit and public debt issuance. In the beginning, this task was eased by the extraordinarily low cost of international borrowing. That era came to a close in 2016, however, when the United States Federal Reserve started to raise interest rates. Neither Mr. Macri nor his team appears to have grasped the significance of this change for their gradualist strategy.

There was good news at the beginning of 2018, when Argentina announced that its accumulated public deficit (for obligations not listed in the budget, such as those for public services and utilities, covered by short-term borrowing) was down to 3.9 percent at the end of 2017, from a high of 6.5 percent in Kirchner’s last year as president. Economic growth accelerated to the fastest rate in five years in February 2018, the last month for which data are available. Also in February, for the first time in 13 years, net public spending actually declined – thanks to a huge decline in subsidies for public services. Even employment inched up in the first two months of the year, although INDEC noted an increase in “informality” – part-time, unregistered work or activity – which is a sign of low confidence in future economic prospects.

Union members are used to having their wages indexed to match or keep ahead of inflation.

In fairness to the government, gradualism usually delivers gradual economic improvement, not an immediate boom. Also, President Macri is trying to operate with a minority coalition in parliament, which limits his maneuvering room. And finally, social conditions in which 30 percent of the population live below the poverty line makes a shock-therapy approach an unattractive alternative for elected leaders.

Hurdles ahead

The main reform President Macri promised for 2018, an overhaul of the labor market, presents him with the greatest political difficulty of all, especially now that it is clear that he will not meet the target which he had used in negotiating labor contracts. Over the past 50 years, Argentina’s official labor market developed into a hybrid that is part corporatist and part social welfare. At the same time, 40 percent of the workforce is unregistered. Most of the formally employed are organized in sectoral or industry-wide unions that negotiate their wages and benefits with the state, federal or provincial authorities. Union members are used to having their wages indexed to match or keep ahead of inflation. They also take for granted health, retirement and other benefits that would be the envy of workers in other parts of the world.

The difficulty of negotiating wages with the teachers’ unions of Buenos Aires province, with nearly 300,000 dues-paying members, can be easily imagined, just to take one example. For the coming year, the union reps are demanding wage increases of 2 percent above last year’s rate of inflation (25 percent), while government negotiators are only willing to peg wages to the Finance Ministry’s (significantly lower) inflation forecast for 2018 (17 percent). At this writing, the teachers have rejected an offer of a 15 percent increase in base pay, plus performance-related bonuses that could add another $1,000 to teachers’ monthly salaries. There have already been several strikes. The province offered bonuses as part of an effort to create quality and training standards for teachers, which is an element of the Macri government’s long-term national competitiveness strategy.

Another problem with corporatist labor organizations is that they give union leaders significant political and economic power, which on occasion is abused. That seems to be the case with Hugo Moyano, the leader of the umbrella labor organization, the Confederacion General de Trabajo, or CGT. Mr. Moyano is also the head of the truck drivers’ union, one of the largest and most strategically positioned in the country. He, his wife and their children are all under investigation for money laundering, tax evasion and criminal activities. Increasingly isolated from his fellow union leaders, Mr. Moyano is supported mainly by a left-wing group of social agitators known as “piqueteros” (picketers), yet still has the power to make the president’s life difficult.

Telling nickname

Mr. Macri’s political problems do not end with Mr. Moyano. The president must hold together a three-party coalition; negotiate federal subsidies with 23 provincial governors, 19 of whom belong to the political opposition; and push through administrative, judicial and labor-market reforms to satisfy his core constituency and the OECD.

Through it all, Mr. Macri has shown a knack for improvisation. He has yet to announce an overall strategy, preferring to “play it by ear.” There is an Argentine term for a soccer player who is better at dribbling the ball than passing and scoring – a morfon. The label has stuck to Mr. Macri. Perhaps like the great football star of a generation ago, Diego Maradona, Mauricio “Morfon” Macri is hoping that the “hand of God” will help him through the tough field ahead.

IMF to the rescue

Facts & figures

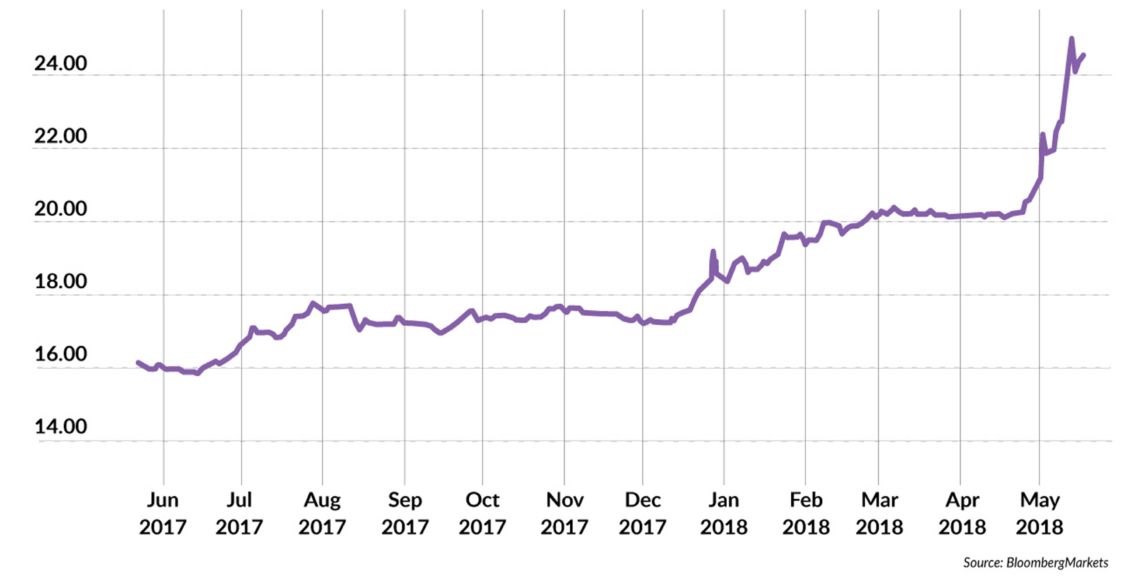

U.S. dollar-Argentine peso exchange rates, July 2017 to May 2018

By April 2018, the government’s economic policies seemed to be delivering, despite grumbling that the improvement was not fast enough. Annual inflation remained stuck above 20 percent. The peso kept weakening. On occasion, the currency depreciated so much that the Central Bank of Argentina was forced to dump dollars onto the market, several times in excess of $1 billion per day. By the first week of May, these interventions totaled nearly $10 billion, a staggering amount for a country with foreign reserves of only $55 billion. Then the market fell apart.

In the second week of May, the dollar jumped nearly 10 percent against the peso. The flight from the peso was on. In response, the central bank raised the benchmark interest rate from 27 percent to 40 percent. Two days later, President Macri announced that Argentina would ask the IMF to backstop its efforts to stabilize the economy.

It was a sign that the Morfon had better start scoring. May’s financial crisis comes just as the fractious opposition appears poised to join together to pass a bill limiting any increase in fees for public services, including the so-called big tariffs, or tarifazos. These tariffs will be targeted by the IMF as a prerequisite for any standby loan, which will only mobilize the opposition because of Argentina’s painful history with the multilateral lender. Negotiations with the IMF appear to be going well for Argentina. In the short term, praise from the IMF should shore up Macri’s political position. At the same time, the IMF demands to lower subsidies and cut the fiscal deficit will serve as cover for his economic team in the months ahead.

If Mr. Macri can avoid a catastrophe, he may be able to shore up his political base.

The president must hold his coalition together and negotiate with the opposition to stay in control of both the political process and the loan talks. How Mr. Macri handles this crisis will affect the economy’s short-term health and his own prospects for reelection in 2019. It will also determine Argentina’s ability to play a larger role in world affairs, which Mr. Macri had so wanted to enhance through the G20 meeting in November 2018.

Scenarios

In the months ahead, President Macri will use the IMF’s support to stabilize the currency, taking steps to reduce the country’s current account deficit and start “rationalizing the economy,” as the IMF puts it. To make this scheme work, he will need to cut a deal with the moderate Peronists to stop legislative curbs on his control over economic policy. If Mr. Macri can avoid a catastrophe, he may be able to shore up his political base. Almost no one wants a replay of the disastrous 2001 default. Even so, the Morfon will have to do some very fancy footwork to keep his chances of a second term viable ahead of next year’s presidential elections.

A less likely script has the opposition holding together and blocking Mr. Macri’s fiscal policies. Such a political impasse would waste the IMF’s support and plunge the economy into a severe crisis.

Even this grim scenario would not match the drama of Argentina’s 2001 default. But by robbing the country of direction, it would destabilize domestic politics and return the economy to stagnation. Under this scenario, the November G20 meeting would become a master class in how not to govern an emerging market.