Israel-Sudan deal offers hope for stability in the Middle East

In October 2020, Israel and Sudan signed an agreement on normalizing relations. The pact is significant for its potential to stabilize Sudan and generate momentum toward Middle East peace. The question now is whether the new U.S. administration will support the deal.

In a nutshell

- The Israel-Sudan deal of October 2020 ends decades of hostility

- Khartoum sees it as a chance to get its economy on track

- The Biden administration’s support will be crucial to secure the peace

On October 23, United States President Donald Trump announced that Sudan was normalizing its relations with Israel. The news came as no surprise: it was an outcome the U.S. State Department had long been working to achieve. The new agreement is markedly different from those that Israel recently concluded with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. There was little rancor between those two Arab states and Israel as the sides had never been engaged in a military conflict against each other. Sudan, however, has long harbored hostility toward the Jewish state.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, a Sudanese contingent fought alongside the Egyptian army. It was in the Sudanese capital Khartoum that the extraordinary summit of the Arab League convened after the Six-Day War in 1967 and issued its famous resolution containing the “Three Nos”: no to peace with Israel, no to recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel. For many years, Iranian explosives and ammunition en route to Gaza transited through Sudan, provoking Israeli raids on the convoys.

Sudan harbored Osama bin Laden and allowed radical organizations to establish offices in Khartoum.

Sudan drifted into fundamentalism. Its legal system was based on Sharia and the country became deeply involved in jihadist terrorist activity. It harbored Osama bin Laden and his entourage from 1992 to 1996 and allowed radical organizations such as Hamas, Hezbollah and the Muslim Brotherhood to establish offices in Khartoum. It even hosted the al-Qaeda jihadist who masterminded attacks on the American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998, leaving 224 dead, as well as the attack on the USS Cole in 2000, in which 17 sailors were killed. As a result, the U.S. branded Sudan a state sponsor of terrorism and imposed economic sanctions.

Internal strife

The country has also undergone several internal conflicts. The predominantly Christian and polytheist southern part of the country revolted against the strict Islamic laws, triggering a bloody civil war that ended with secession. Newly independent South Sudan retained the country’s huge oil reserves and immediately began establishing diplomatic relations with Israel in July 2011.

During the long rebellion in the poor, underdeveloped western region of Darfur, the Sudanese army, assisted by the Janjaweed militias, massacred an estimated half a million people. Some three million were displaced. The International Criminal Court (ICC) accused President Omar al-Bashir of crimes against humanity, war crimes and what became known as the Darfur genocide. The Arab League rejected the ICC’s arrest warrant and President al-Bashir avoided prosecution. It was not until his 2019 ouster that the August 2020 Juba Peace Agreement formally put an end to hostilities.

Facts & figures

With former President al-Bashir jailed and facing trial, there was a gradual return to a more secular regime. The death penalty for apostasy was abolished, as was public flagellation. Female genital mutilation was criminalized. These reforms have put Sudan on a path toward becoming less of an international pariah, but its decades of backwardness have left the economy in ruins.

New direction

The first step toward recovery was to be taken off the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism. The new leaders concluded that rapprochement with Israel would help convince Washington to make that move. Sudan could then attract foreign investments and would be eligible for international economic aid. Furthermore, it could benefit from Israel’s know-how in technology and agriculture.

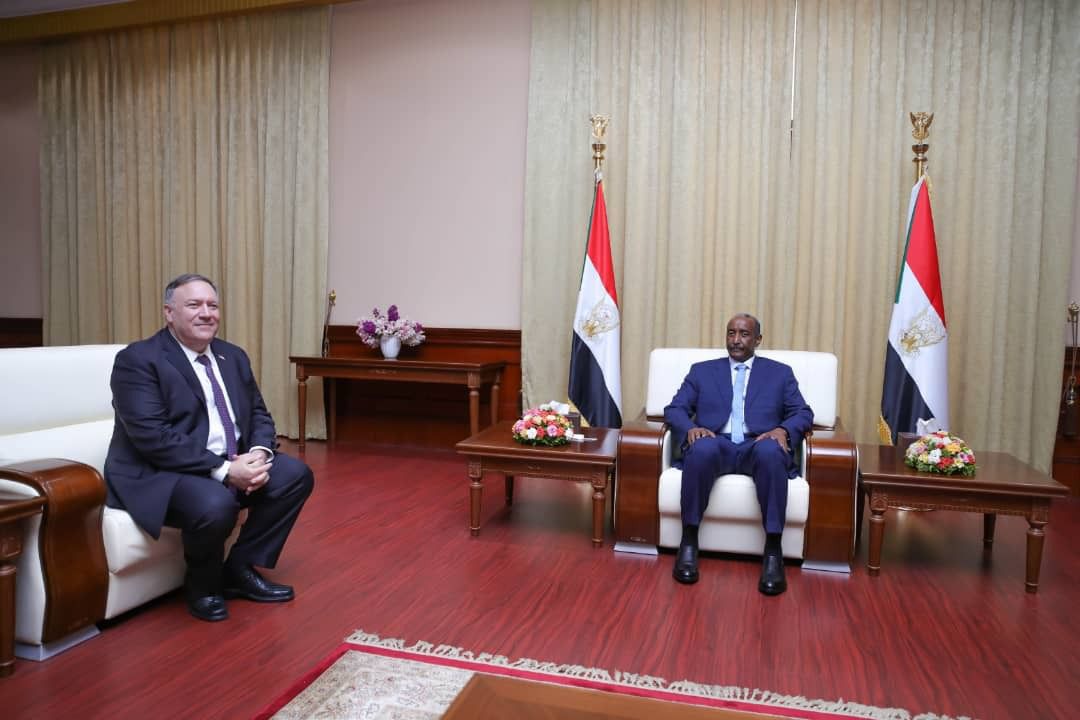

In February 2020, Uganda held a groundbreaking meeting between Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who is serving as Sudan’s transitional head of state, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. There, the countries decided to move toward establishing relations. Discreet negotiations began. Washington announced that if Sudan normalized its relations with Israel and paid $335 million in compensation to victims of the terror attacks for which Khartoum was found culpable, it would be struck off the list and could receive economic assistance.

The problem is that the new regime is a temporary one. It was established after difficult and protracted negotiations between the army and the Forces for Freedom and Change – a coalition of the protest movements that brought down President al-Bashir. The two sides agreed on an interim constitution providing for a Sovereignty Council led by a member of the armed forces to replace the presidency, an interim civilian government and a Transitional Legislative Council – which is yet to be established. This provisional government is due to rule the country until 2022 when new, democratically elected officials are supposed to take over.

Hurdles

Meanwhile, there are serious differences of opinion on security and economic issues between the army and the civilian government. From the outset, Lt. Gen. al-Burhan favored Sudan normalizing relations with Israel. However, Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok objected, on the grounds that the interim government does not have the legitimacy to take such a significant step. After Washington offered economic assurances, the prime minister relented.

Time is critical, since the longer the deal awaits ratification, the more opposition to it can grow.

President Trump alluded to some of the problems in his October 23 announcement, when he acknowledged that Sudan and Israel had been at odds “for many, many years.” The deal does not include any commitment to make a formal peace agreement or establish full diplomatic relations – as was the case in Israel’s pacts with the UAE and Bahrain. Instead, the relationship will move forward step by step, with deals on economic cooperation – which Sudan desperately needs – coming first.

Both Lt. Gen. al-Burhan and Prime Minister Hamdok have said the as-yet nonexistent Transitional Legislative Council must ratify the deal. No one knows when the relevant political factions will manage to hammer out the details so that the council can be formed. Time is critical, since the longer the deal awaits ratification, the more opposition to it can grow. So far, resistance has been minor. The three political parties that oppose the agreement have organized small street protests, but the public as a whole does not seem to have rejected the move.

On the other hand, several key public figures have spoken openly in favor of normalization. Dr. Mubarak al-Fadil, chairman of the National Umma Party, called the deal a “historic opportunity” to address Sudan’s economic issues. Abdul Wahid al Nur, founder and chairman of the Sudan Liberation Movement, went further, saying, “First, we need to address our problems, not those of the Palestinians.”

American question

The new American administration will be vital in keeping the agreement intact. President Trump had been instrumental in bringing it about. There is now fear that the administration of President-elect Joe Biden will take a more hostile tack toward Sudan.

Washington has a trump card: Sudan still needs to be taken off the list of state sponsors of terrorism. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who was in charge of the negotiations, assured Sudan that if it normalized relations with Israel and paid the compensation, it would be struck from the list and receive economic assistance, as promised.

While President Barack Obama began lifting economic sanctions on Sudan, the process was completed by the Trump administartion in 2017, on the grounds that the country had made progress in fighting terrorism. The move was strongly criticized at the time because it was not accompanied by the payment of compensation. Sudan was able to trade on global markets, but international economic institutions and many companies – including large American oil firms – still refused to engage with Khartoum.

Following heavy American pressure, Prime Minister Hamdok placed the $335 million in escrow and accepted normalization with Israel in principle. On October 31, 2020, the Sudanese government signed an agreement with the U.S. to stop lawsuits against Sudan in American courts and give the country sovereign immunity. The U.S. Congress must now pass legislation to implement the deal – a sensitive subject since it involves granting immunity to individuals involved in suits over terrorist attacks.

Once that happens – and once Sudan is officially taken off the list of state sponsors of terrorism – more American firms will feel they are on firm footing to begin doing business with Khartoum.

Opportunities

Normalization has slowly but surely begun. An Israeli delegation flew to Khartoum for talks about security cooperation in late November. (The Sudanese government denied any knowledge of the visit, citing the principle that no communication between the countries’ governments should take place before the normalization deal is ratified.) A larger delegation is expected to follow in the coming weeks to discuss economic cooperation.

The talks will focus on agriculture, which is of paramount importance to Sudan. Two-thirds of the country’s workforce is employed in the sector, and it is badly in need of modernization. Most farmers use outdated technology, which leads to substantial amounts of wasted water. Sudan has vast regions suitable for agriculture, the benefit of the Nile and bountiful rains. If it improves its methods, it could become Africa’s breadbasket. Israel is known for its innovative agricultural technologies and could help Sudan in this field.

Israel could become a significant partner in Sudan’s economic development, helping to stabilize the new regime.

Sudan’s Red Sea coast has enormous potential to attract tourists, even from Israel. Reportedly, several Gulf states are considering investments there. Moreover, a growing number of young Sudanese are well-educated and speak English. They could help develop a hi-tech infrastructure still in its infancy in the country. Here too, Israel, dubbed “the start-up nation,” could help.

There are other initiatives: Negotiations are ongoing with the Sudanese Aviation Authority to enable Israeli carriers to fly through Sudanese airspace to Western Africa and Latin America. Officials are addressing the fate of several thousand Sudanese who entered Israel illegally in search of work. Now that the process of democratization is underway, some of them will choose to go home.

All told, Israel could become a significant partner in Sudan’s economic development, helping to stabilize the new regime and convincing other Arab countries to normalize their relations with Israel.

Washington’s role

U.S. policy remains a great unknown. Through suitable economic, financial and technological measures, Washington has the power to advance the emergence of a relatively democratic and stable regime in the region. It can also promote normalization measures, convincing an increasing number of Arab states to make peace with Israel. None of this would require the U.S. to tolerate human rights abuses or jihadist terrorism. But its role would be limited to assisting the process, not imposing alien cultural norms.

Israel, Sudan and other Arab states will have to wait and see which direction the new American administration takes. Will President-elect Biden be swayed by those who insist that the Middle East adopt Western democratic values? President Jimmy Carter tried that path and failed; so did President Obama, who had no better success but provoked resentment when he withdrew support from Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, a faithful U.S. ally.

Sudan will be a litmus test. With suitable encouragement, it could become a democratic country – in Middle Eastern terms – ensuring the welfare of its citizens and potentially even contributing to regional peace. Without that encouragement, it may fall prey to its old demons and threaten the stability of the region.