Swiss economic success: diversity as capital

Nothing seems to stop the prosperity of the Swiss economy. The country’s highly diverse economy and its unique political system together form an ecosystem that is amazingly productive and resilient. The question, however, is how long the Swiss can manage to shield their order from the globalized world’s homogenizing pressure.

In a nutshell

- More than 99 percent of the total number of Swiss enterprises are small- and medium-sized firms

- The Swiss view heterogeneity as a form of capital

- Swiss regulators opt for superintendence applied to the general framework of activities, not specific sectors, industries or technologies

- The country’s political system is consensus-oriented and professional politicians do not dominate it

In 2018, the Swiss economy grew 2.5 percent. For 2019, the Federal Expert Group for economic forecast expects it to expand by 1.5 percent. Switzerland’s gross domestic product (GDP) has been increasing by between 1 and 3 percent yearly for nearly a decade. Turmoil in the European Union, the “trade war” between the United States and China as well as a strong Swiss franc do not seem to stop the prosperity of the country’s economy. What is its formula for success? And, will it last?

Switzerland is commonly associated with its banks and watches. Facts, however, tell a different story. Only about 9 percent of Swiss GDP is traceable to financial services. Manufacturing makes up around 18 percent, retail almost 15 percent; the most significant part of GDP, some 31 percent, is generated in other services.

While it is also true that every year more than 25 million watches and clocks are produced in Switzerland, they only account for 9 percent of Swiss exports. Chemical and pharmaceutical products make up more than 44 percent of the country’s total exports; machinery and electronics over 14 percent. By the way: Switzerland manufactures and exports twice as much coffee- and tobacco-based products than chocolate- and cheese-based ones.

Switzerland understands heterogeneity as a form of capital.

These statistics might seem anecdotal, but the story behind them elucidates an important, perhaps even the most critical, facet of the Swiss economy: its diversity. The world’s 20th largest economy, with a nominal GDP of $679 billion (2018, according to the World Economic Forum) is a mix of manufacturing and services, of high-tech and low-tech, domestically oriented businesses and globalized agents. The Swiss economy is dominated by small- and medium-sized firms, which constitute more than 99 percent of the total number of its enterprises.

Unity without uniformity

Switzerland understands heterogeneity as a form of capital. Different types of companies with varying models of business enrich each other in a positive feedback loop. They can explore common ideas through cooperation. Through competition, they can challenge each other. Either way, the more businesses with diversified ideas and different business models, the more collaboration and competition is possible. This leads to higher productivity and innovation.

Two examples illustrate this system. As Uber entered the Swiss market in the city of Zurich, some of the incumbent taxi operators teamed up to develop their own app – which was inspired by Uber but fitted to the Swiss market, for example through the integration of the train schedule. With the entrance of Uber and the response by traditional taxis, the overall market has grown in terms of revenue. In the Swiss Canton (state) of Zug, developers of distributed ledger technology (DLT) are thriving. While most of their products are yet to achieve scale, the companies are developing new applications at a record-high pace.

There is yet another part to the story. Up to now, Swiss authorities refrained from regulating Uber or DLT. This, in part, explains the country’s dynamism and is another feature of Swiss heterogeneity. As a rule, regulators opt for superintendence applied to the general framework of activities, or the whole economy. Regulation geared at specific sectors, industries and technologies is rare and has been continuously reduced over the past 20 years. The idea behind it: sectorial regulation tends to homogenize business activity. Neutral frameworks and conditions incentivize diversity.

Economic freedom and individual responsibility

Neutral framework conditions go hand in hand with economic freedom. This principle is enshrined in the Swiss constitution. It stipulates that all economic activities not forbidden or separately regulated are open to be pursued by anyone. This has immense consequences for the country’s commercial tissue. With very few exceptions, any person is free to open and run a business at any time in Switzerland – independently from that person’s education or experience and mostly without the need for a business license.

Two examples here: If a baker wants to provide financial advice, he or she can set up and run such a business. No license is required, no sectorial regulation applies and, in the beginning, the business does not even need to be registered. There is no need for incorporation and there is no formality applying to this endeavor. Of course, the baker can register, join a self-regulating body and incorporate the firm. Ultimately, though, this is the owner’s decision. Similarly, if a hairdresser wants to set up and run a company making plastic bags, the same freedom facilitates it: there are no market entrance barriers.

Most Swiss companies prefer to export to international markets instead of having a physical presence there.

The flip side of this freedom is that individual businesses are solely responsible for their success or failure. With a yearly bankruptcy rate of 1 percent, Switzerland shows more business failures than most European nations. However, this is regarded as part of a system that values individual responsibility. With very few exceptions, most companies have neither an explicit nor implicit state guarantee. They are not subsidized. Individual responsibility is at the center of economic freedom.

Open economy and private property

Economic freedom and individual responsibility, together with the openness of the economy and private property, are factors contributing to Switzerland’s diversity as the driver of its economic success. Many Swiss businesses, large and small, are global players. Some 53 percent of Swiss exports go to the European Union, but the U.S. and China are becoming increasingly important markets. Most Swiss companies prefer to export to international markets instead of having a physical presence there. The general feeling is that almost no country protects private property as well as Switzerland does. Private property is understood as an economic and moral basis for economic activity.

Facts & figures

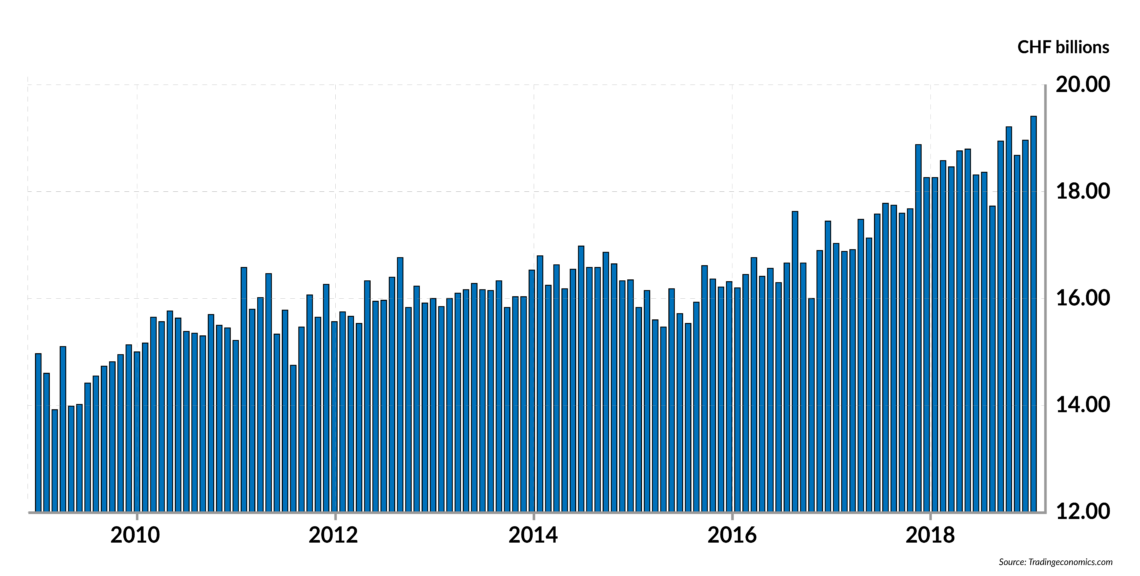

Switzerland's monthly exports

Two examples illustrate this: The Swiss government is pushing for the abolition of all tariffs worldwide. It wants to take the first step and unilaterally abolish all import tariffs on industrial goods. Everyone profits from free trade, the thinking goes, but even if a country opens up unilaterally, free markets put pressure on the domestic industry, driving it to improve. On the other hand, a small Swiss company that produces tinting systems prefers to make them at home and export the product to the two main markets, India and the U.S. This firm knows that it would be cheaper to manufacture in the target markets. And it is aware of the high tariffs with which their products are confronted. However, it considers its private property, machinery and proprietary formulas better protected in Switzerland and is willing to pay a premium for keeping these assets safe.

Openness and home bias lead to a dilemma. Swiss products are expensive, but they tend to fare well in domestic and international markets. Apparently, Swiss businesses find customers willing to pay the premium. But as often as that, it is the entrepreneur who pays, too. Profit margins in Swiss businesses are usually lower than in comparable countries; the average profit margin across the diversified economy is around 2 percent.

Political stability and continuity

Another element contributing to the prosperity of the Swiss economy is political stability. Politics is also regarded as a matter of individual responsibility. Most holders of political office are either entrepreneurs or employees. In addition to officeholders being private citizens engaged in politics (as opposed to career politicians), four popular votes per year ensure that the broad Swiss population remains attuned to political decision-making. This leads to a constant brokerage of political consensus.

In Switzerland, professional – or better: full-time politicians – are a rare phenomenon. Such may be more often found in the executive and the judiciary branches. But even there, many judges and canton-level ministers and indeed almost all mayors are part-time. Also, all major political parties are represented in the national government. They do not forge a formal coalition, nor do they sign a contract to form a government. Their presence in it is a consequence of Swiss-style consensus.

The Swiss political system is coupled with free enterprise on a cultural and personal level.

Attuning citizens to politics and incentivizing politics to be based on consensus lead to political stability. On the one hand, Swiss politicians exert normal economic activities. On the other, building consensus harnesses the capital coming from the heterogeneity of views. Both these features prevent politics from regulating out of tune with the economy and from radical change. The Swiss political system not only mirrors the nation’s economy regarding diversity as capital; it is also coupled with free enterprise on a cultural and personal level.

Three scenarios for the future

The Swiss economic system, intrinsically tied up with the country’s political workings, has been the key to the Alpine nation’s success and prosperity. This system, however, is under constant pressure for change. As Switzerland interacts internationally, it adapts its system. As political discourse becomes more confrontational, politics regulate more. Since the future is open-ended, the future success of Switzerland is indeterminate as well. Devising three possible scenarios helps to conceptualize, how it might evolve.

THE BEST CASE

Switzerland remains unique. It retains heterogeneity in its economy with many differences across sectors, regions, activities and business models. It differentiates itself more and more from its international competitors, for example, with less regulation, a greater willingness to take risks, strengthened property rights and low taxation. On the political level, consensus-driven decision-making and popular votes create a strong bond between the country’s political realm, the economy and the population at large.

THE WORST CASE

Switzerland becomes more like the rest of Europe. Driven by European integration, Switzerland adapts to the EU by accepting its rules and regulations and recognizing its Court of Justice. Through this, the regulatory burden increases, the social welfare system begins to mirror the EU’s solutions and also offers services to EU citizens. As a consequence, the country’s business becomes more homogenous, there is less entrepreneurial activity and innovation. More expensive state policies lead to higher taxation. The political system loses its integratory function, through the “professionalization” of politicians on all levels of government.

A POSSIBLE OUTCOME

Switzerland becomes more like the U.S. While the country’s economy continues to be heterogeneous across sectors, regions, activities and technologies, the central government plays an expanded role and sectoral regulations become common. Entrepreneurs, the general public, and politicians strive for “fair” competition, regulating more and enacting business licensing and other market-entry barriers. Individual responsibility faces more trade-offs with collectivistic policies. International standards are quickly applied to the domestic economic and political processes, often after having been modified. Politics remains based on consensus but becomes more confrontational; on the federal level, full-time politicians become the norm.

Scenarios

It is no secret, in the end. Economic freedom, an open economy, property rights, individual responsibility, as well as political stability and continuity are the main factors driving the Swiss economic success. The key, however, for understanding Switzerland is that all these factors together create an environment for differentiated business models and products. Diversity is the soul of the system, the primary capital source for the Swiss economy.

The future of the Swiss success hinges on whether the country will be able to protect its uniqueness, especially vis-a-vis the homogenizing force of international standards and European regulations. In the best case, Switzerland dares to remain different from any other system. The best case, however, is not the most probable.