Thailand between monarchy and modernity

Thailand is more monarchy than democracy, an arrangement that worked to its advantage during the Cold War but is now holding it back. At issue is whether the country can find a new balance between the forces of tradition and modernity. If not, Thailand may become too weak to resist China’s expanding influence in the region.

In a nutshell

- Thailand’s dysfunctional politics is holding back its potential

- The monarchy-military alliance has resisted democratic reforms

- The system worked well during the Cold War but is ill-suited for the 21st century

- Thailand’s prosperity depends on finding a new way for the monarchy and democracy to coexist

For all its immense potential, Thailand frustrates as much as it beckons. The country of 70 million has an almost half-trillion-dollar economy at the heart of mainland Southeast Asia. Having earlier eluded colonialism and communism, Thailand became a founder and birthplace of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a market of 650 million people, with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) approaching $3 trillion. In geopolitical terms, Thailand benefits from close historical ties with China harking back to the ancient tributary system, but without a shared border that could cause friction. Yet Bangkok also has a treaty alliance with the United States that dates from the thick of the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, on top of a friendship document signed in 1833.

With so much going for it geographically, historically and economically, Thailand has disappointed as an inward-looking laggard. It has been beset by political polarization and a protracted crisis that ultimately begot its current military government under a retired general and former army strongman, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha. Thailand’s near-term political fortunes and its road back to democratic rule will have a big impact on the future of Southeast Asia’s democratization, as well as on the interplay between China and U.S.-led Western democracies.

At issue is whether Thailand can find a new balance between being a kingdom and a democracy. The country is nominally a constitutional monarchy, but anyone who has spent significant time there knows it feels like a kingdom more than anything else. Thailand has gone through 19 constitutions and 13 successful coups over the past 86 years since the first charter replaced absolute monarchy in 1932. For most of that time, the country was under the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej, whose remarkable reign began in 1946 and lasted seven decades.

The monarchy’s lopsided role explains Thailand’s lingering political malaise.

Monarchy and democracy in Thailand have become entwined in an inverse relationship. A strong monarchy, with its symbiotic ally in the military, meant a weak democracy, while any strengthening of democratic institutions would have entailed reforms of the monarchy. The monarchy’s lopsided role explains Thailand’s lingering political malaise over the past decade, but it is understandable considering the country’s path through the Cold War years.

Economic boom, political reform

Contemporary Thailand is a product of sociopolitical and economic development during King Bhumibol’s 70-year reign – the first five decades during the Cold War and the last two in the 21st century. The question is whether it can become a modern democracy, as the international community expects and the population demands. To do so, it will have to reconcile the overlapping forces of these two eras. Since the beginning of the 21st century, Thai politics has been turbulent and polarized, marked alternately by elections and coups from either the military or the judiciary. But the roots of Thailand’s political crisis lie elsewhere.

From 1947 to 1997, Thai GDP increased rapidly, with growth averaging about 6 percent per year. What began as an agrarian economy with poor living standards and rudimentary infrastructure became East Asia’s “fifth tiger,” alongside South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. The long boom ended with the 1997-98 economic crisis, but by then Thailand’s sociopolitical foundations had been transformed. People had more means, education and information, along with broader exposure to the outside world.

This prosperity culminated with unprecedented political reforms, capped by the 1997 constitution that promoted greater transparency and accountability in the political system while also laying the foundations for more government stability and effectiveness. Together with a network of associates who had amassed new wealth from stock market growth and global finance, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra (2001-2006), an ambitious telecommunications industry tycoon, was able to benefit from postcrisis recovery and the new politics after the 1997 constitution was promulgated.

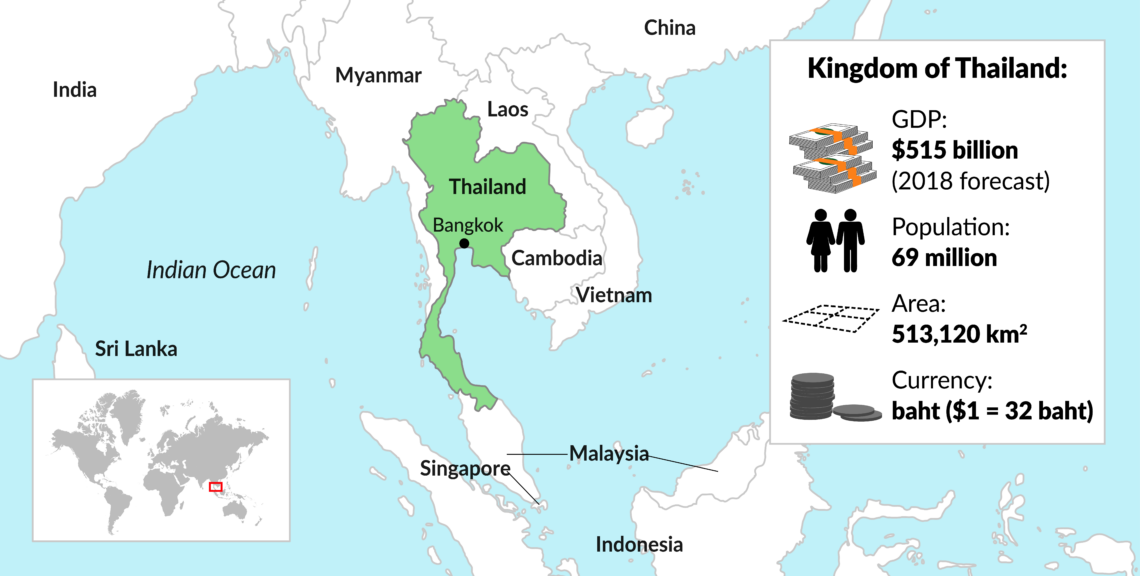

Facts & figures

Thailand: in the heart of Southeast Asia

This is the main reference point for many Thailand-watchers: focused on Mr. Thaksin’s political machine, the 1997 constitution, two military coups, and street protests dominated by anti-Thaksin “yellow shirts” and “red shirt” supporters of his policies favoring the poor. It was as if elections and democracy bloomed when he gained power, only to be turned back time and again by putsches and conservative forces. In fact, the long boom and the 21st-century democratic politics it engendered would not have been possible without the political institutions that arose from the Cold War.

Military-monarchy alliance

The first dozen years of King Bhumibol’s reign were tentative. The role of the monarchy was murky and at a low point. It was only after a partnership between the monarchy and the military was established with the 1947 coup and steadily expanded from another putsch in 1958 (in response to communist expansionism) that King Bhumibol consolidated his rule. Rooted firmly in the Thai-U.S. alliance, the symbiotic relationship between the military and monarchy was indispensable for steering Thailand through the Cold War. As the state bureaucracy began to expand rapidly from the early 1960s, Thailand’s Cold War political order was soon set.

This order revolved around the military, monarchy and bureaucracy. Notwithstanding elections and political parties that came and went, including the liberal left-wing movement of the mid-1970s, this trinity of traditional institutions was what might be called “Thailand’s Cold War fighting machine.” Yet King Bhumibol’s reign was so successful in combating communism and nurturing economic development that it became a victim of its own success. Sustained economic growth eventually emboldened previously marginalized voices to speak out, as democratization and political liberalization took root. Equally important, international circumstances changed. There were no more communists to fight, and instead, there were new international norms of democracy and human rights that had to be followed.

Thailand’s two coups in 2006 and 2014 and the politicized judicial maneuver in 2008 – the three blows that dislodged the Thaksin-aligned governments – were a rearguard action by the old political order to forestall change and thwart Mr. Thaksin, whom they see as an upstart and a usurper. The military government now in power comes straight from the Cold War decades. The royalist yellows are beneficiaries of the same era, not ignorant of the 21st century but demonstrably insistent on entering it on their own terms. The red shirts are a 21st-century movement, the beneficiaries of the development and growth of Cold War years, but now more exposed to and integrated with the outside world.

The international community and domestic population demand elections and popular rule.

The international community and domestic population demand elections and popular rule. The traditional forces’ best way out is to come up with one or more political parties that can protect their interests, rather than pin their hopes on long-term military supremacy. In other words, the military’s best outcome is to share power with democratic institutions during a transitional period and then to “civilianize” if it wants longer-term influence.

An indefinite military dictatorship – the date of the next election has been postponed several times and is now set for February 2019 – will not be palatable to Thais. They are fed up with subpar economic performance and corruption under the ruling generals. The military leaders have been in power for more than four years, longer than most elected governments. Tensions are likely to mount as the military government becomes untenable, while political parties remain weak and fragmented. The situation has been exacerbated by the 2017 constitution, which was drafted by a committee appointed by the military to perpetuate its influence and keep democratic institutions feeble in the long term.

The king’s task

Hence the existential task facing King Maha Vajiralongkorn after his father’s long reign. The monarch in Thailand has been considered the final arbiter and power broker in times of crisis, but that role was specific to King Bhumibol due to the moral authority he had accumulated. Thailand now finds itself in uncharted waters, with a new king in an old, traditional monarchy that is equipped with quasi-feudal privileges. It is a painful irony for Thais that King Bhumibol’s reign was so successful and necessary in its time, but has left so many challenges behind. The country is now led by a king who does not command the respect his father did, but who nevertheless inherits the dominant monarchy he rebuilt.

After ascending to the throne in December 2016, King Vajiralongkorn has spent most of his time abroad in Europe, in southern Germany. (His father went abroad only for two days, for an official ceremony in Laos, in the 49 years before his passing.) Notwithstanding his absence, King Vajiralongkorn has consolidated his constitutional prerogatives, personal security and palace finances. The new constitution was revised to enable the king to be abroad without having to designate a regent and to maintain the monarch’s role as final arbiter in cases of complete political breakdown.

Thais are willing to give their new king a chance because the monarchy is so integral to their collective identity.

King Vajiralongkorn has transferred security-related units from the military and police to a new unified agency based at the palace. The multibillion-dollar Crown Property Bureau is now run by a new management board under his guidance. The once-powerful Privy Council, the monarchy’s advisory body of “elders” from the military, judiciary and bureaucracy, has been shuffled to include the monarch’s loyalists. The newly promoted chiefs of the armed forces are also close allies of the king.

Yet the Thai people are willing to give their new king a chance because the monarchy is so integral to their collective identity. However King Vajiralongkorn finances his livelihood at home and abroad, the Thai system will probably tolerate it if political stability is regained and the economy grows by 3-4 percent or more. Thais will want to see an institutional rebalance in favor of political parties, parliament, electoral rule and a popular mandate. Thai politics is unruly and unwieldy, but it was largely workable in the 1980s and 1990s with regular elections and civil-military power-sharing.

King Vajiralongkorn is uniquely positioned to implement this recipe for stability through a new constitutional order that accommodates both monarchy and democracy – a flexible mix of not too much one or the other, allowing democratic institutions to strengthen and the monarchy to adjust.

If Thailand cannot regain a new balance, it could become prey to China’s authoritarian embrace. But if the electoral politics can return to regular elections and democratic changes of government, Thailand will be stable enough to retake its leadership role among emerging democracies and within ASEAN.

Thailand’s fate, in other words, rests squarely within its own control, despite rivalries and machinations among bigger states in the neighborhood. But what happens in Thailand will be pivotal well beyond its borders – in terms of global democratization and great-power rivalries, not least between China and the U.S.