Togo faces two years of turmoil

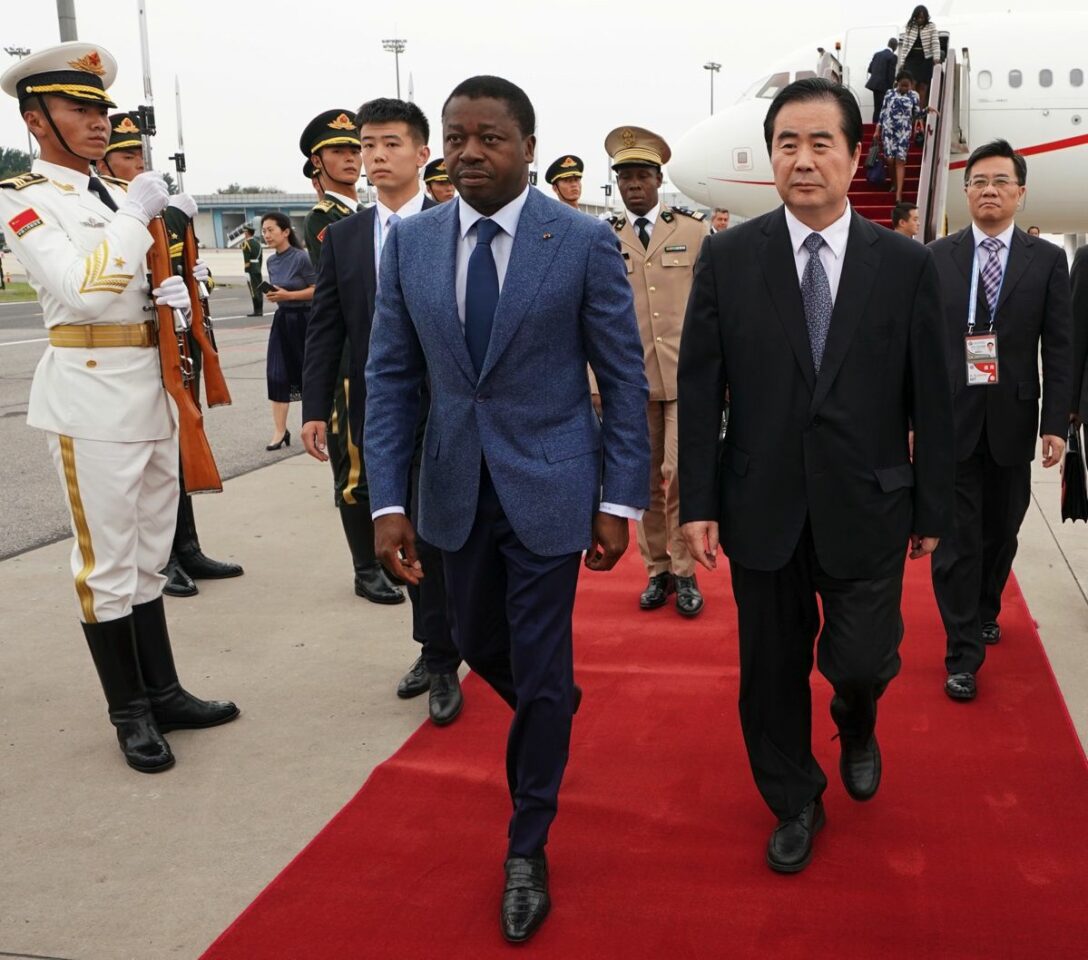

Togo is another instance of “third termism” in sub-Saharan Africa, as a long-time president determined to stay in power collides with an angry populace. President Faure Gnassingbe loses grip ahead of the 2020 presidential elections, while his opponents may be able to count on intervention from ECOWAS, West Africa’s regional bloc.

In a nutshell

- The Togolese president’s bid to extend a family dynasty is faltering amid popular unrest

- Faure Gnassingbe’s regime has eased up on the opposition and begun fiscal reforms

- Domestic and foreign pressure to oust Gnassingbe may lead to protracted turmoil

For the past year, Togo has been in a political deadlock. In August 2017, the opposition supporters took to the streets to protest against the ruling regime and demand political reforms. Forced to react, the government adopted a carrot-and-stick strategy, reaching out to the opposition parties while cracking down on street protests.

Togo’s political crisis reflects a more general trend in sub-Saharan Africa. President Faure Gnassingbe, a leader with a mixed record who came to power by irregular means, is now trying to extend his mandate. His political ambitions, however, face increasing popular resistance. While the Togolese government seems committed to important and long overdue economic reforms, it has lost much of its political capital.

With legislative elections initially scheduled for July 2018 and now postponed until November, and presidential elections due in 2020, the next two years promise to be eventful, reflecting the difficulty in reconciling political and economic reforms.

Family dynasty

Located in the Gulf of Guinea, Togo – a country of 8 million people – is one of Africa’s smaller states. In 1967, seven years after independence, Colonel Gnassingbe Eyadema seized power in a coup and ruled the country with an iron fist until his death in 2005. Like Idi Amin in Uganda or Mobuto Sese Seko in Zaire, Eyadema based his personal and authoritarian rule on the loyalty of a strong army and the ruling party, extensive patronage networks and the neutralization of any opposition.

After Eyadema’s death, his son Faure Gnassingbe was appointed president by the military. The move contravened the country’s constitution and provoked strong domestic and international opposition. The European Union, the United States and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) enacted sanctions against the country. The African Union, under the presidency of Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, then forced Mr. Gnassingbe to step down and go to the polls.

Togo’s president has been reelected twice amid allegations of vote rigging and intimidation.

Faure Gnassingbe won the 2005 elections with over 60 per cent of the vote. However, the results were questioned by international observers and strongly contested by the domestic opposition. After the elections, more than 800 people died in a wave of repression.

Faced with ongoing instability and international ostracism, Mr. Gnassingbe was forced to sign a Global Political Agreement (GPA) with a coalition of opposition parties (the Union of Forces for Change) that called for a national unity government and institutional and electoral reforms. However, the GPA’s terms have not been respected, and President Gnassingbe has been reelected twice (in 2010 and 2015) amid allegations of vote rigging and intimidation.

Economic progress

On the economic front, Faure Gnassingbe has made important strides, particularly considering the country’s situation under his father. Since 2005, Togo’s growth rate has accelerated, reflecting the positive effects of the global commodities boom, the resumption of foreign economic cooperation, and the emergence of a Togolese private sector. At the same time, the government has managed to decrease the poverty rate (from 61 percent in 2011 to 55 percent in 2017).

In 2017, Togo signed two loan agreements with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, both of which are aligned with the country’s National Development Plan for 2018-2022. Structural reforms are being implemented, at least according to the IMF, and state expenditure is being reduced. The African Development Bank projects that private investment could become the country’s main source of wealth creation over the next years. Productivity in the farm sector – the backbone of the Togolese economy – has increased in recent years with the implementation of the National Agriculture and Food Security Investment Program.

The government also seems committed to develop and exploit two key assets: phosphate deposits (Togo is among the world’s top 20 producers, with reserves estimated at 60 million metric tons) and the Port of Lome, the only natural deepwater port in this part of West Africa. Lome is now able to receive extra-large container ships, which represents a major competitive advantage in the region – reinforced by the recent improvements in the country’s road network and at the Lome-Tokoin airport.

Recently, the government also launched an ambitious policy that aims to provide universal access to electricity by 2030 through extensive use of renewable technologies.

Despite these positive signs, however, Togo’s economy is still marked by deep fragilities. The country’s poverty rate remains extremely high, even by standards for sub-Saharan Africa (55 percent versus 42 percent, according to a World Bank estimate for 2013); a substantial part of the population still depends on subsistence agriculture; the informal sector accounts for over 40 percent of gross domestic product and an already challenging business environment has been made even more difficult by political instability.

Political thaw

Togo is far from a democracy, but under the leadership of Faure Gnassingbe, it is no longer a personal dictatorship. Perhaps it is best characterized as a “hybrid regime” that combines democratic institutions and mechanisms with authoritarian power. Since 2005, politics has been largely demilitarized and the space for opposition – although still severely constrained – has increased.

As opposed to his father, who relied heavily on the Kabye ethnic group as a loyal power base, Mr. Gnassingbe has not openly exploited ethnic conflicts. While the president is careful to keep the playing field tilted in favor of himself and the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party, repression has eased – as seen by the intense protest campaigns organized by the opposition parties and civil society organizations.

A 14-party bloc, Coalition 14, now represents the main political threat to Mr. Gnassingbe’s rule.

The Togolese opposition is becoming better organized. The two main opposition parties – the National Alliance for Change (ANC) under the leadership of Jean-Pierre Fabre and the Pan-African National Party (PNP), led by Tipki Atchadam – lead a 14-party bloc, Coalition 14 (C14), which now represents the main political threat to President Gnassingbe’s rule.

While Mr. Fabre has been an opposition fixture for years, the emergence of Mr. Atchadam is noteworthy because he comes from the northern part of the country – traditionally a stronghold of the Gnassingbe dynasty. As a result, C14 has become a movement that spans Togo’s traditional ethnic and regional divisions.

The origins of C14 date back to the 2006 Global Political Agreement, which called for electoral and institutional reforms and the reintroduction of presidential term limits. More than a decade later, these remain the main points of contention in the current crisis. While the government wants early elections before a new electoral law is implemented, C14 is strongly against it. The opposition bloc also insists that term limits be retroactively applied to Faure Gnassingbe, preventing him from running for a fourth consecutive term.

Scenarios

Togo is another instance of “third-termism” in sub-Saharan Africa, as an incumbent president determined to remain in power sets a collision course with an increasingly mobilized society.

As in Burundi, Uganda and the DRC, the Togolese crisis reflects a paradox increasingly visible through the region: elections and constitutions are being manipulated to perpetuate the status quo, even against the will of the majority. However, these manipulations are not without risk to rulers. They also present regional and international actors with a difficult choice between stability (usually regarded as a prerequisite for economic growth) and democratization.

In Togo, two outcomes seem most likely.

Intervention and disruption

Under the slightly more probable scenario, a resilient opposition and outside pressure would prevent Faure Gnassingbe from remaining in power beyond 2020. A crucial role would be assumed by ECOWAS, which may follow the example of Gambia in 2016, when it forced President Yahya Jammeh from power. In rejecting attempts at election rigging or constitutional “engineering” in Togo, ECOWAS would be sticking to its “zero-tolerance” policy regarding military coups.

In this context, even if President Gnassingbe seeks another term, he would be forced to accept an electoral defeat (the most likely result in a free and fair election). ECOWAS’s relative inactivity on Togo to date can be easily explained by the fact that Mr. Gnassingbe held the organizations’ rotating chairmanship before handing it over to Ivory Coast President Jean-Claude Kassi Brou in July 2018.

While this scenario may favor the development of democracy in Togo in the long run, it could also disrupt the government’s fiscal reform efforts and compromise economic growth in the medium term. Political instability would be the rule until President Gnassingbe’s fate is determined by the 2020 elections and their aftermath. During this transition period, most investors and possibly international aid donors as well may adopt a wait-and-see policy. This would take its toll on Togo – a small economy in a region expected to grow by 3.9 percent next year, according to a forecast by the African Development Bank.

Authoritarian trap

The less likely scenario would see President Faure Gnassingbe elected to another term in 2020. This would require, from the government, a series of complicated political maneuvers and a crackdown on the opposition.

While the C14 has given up demanding the president’s immediate removal, it will not compromise on term limits. This means that Mr. Gnassingbe would have to resort to the courts to give himself the possibility of running for a fourth term. To legitimize these ambitions, he would invest heavily in economic growth, pursuing a model of “developmental authoritarianism.”

However, this repressive course would probably prove self-defeating. It would further erode the regime’s legitimacy, strengthening the opposition and increasing the likelihood of outside intervention from ECOWAS. It would also deter investors and disrupt aid flows, strangling the economic growth that President Gnassingbe had hoped would save him.